Introduction: The End of the War and the Reorganization of the State

Following the Spanish Civil War, in a social context of repression and impoverishment, cities offered more opportunities for making a living than the rural world. In addition to the destruction and the severe drought that characterized the entire decade of the 1940s, in the Spanish countryside the confrontation between winners and losers of the war became more personal and intractable. Large cities saw a wave of immigrants fleeing poverty, but in the early post-war years, they did not find an economic and social situation that could support their integration into urban settings. As had happened in the 1920s, informal settlements and slums sprung up in large Spanish cities, which the new authorities found themselves incapable of controlling or organizing. Thus, the Regime inherited the unresolved problem of the expanding suburbs, which only compounded the enormous reconstruction effort. It is no surprise that Franco’s government began introducing legislation on housing in the same year the Civil War ended.

In those early years, the different political families on the winning side were fighting to occupy political and social spaces. At the end of the war and in the early 1940s, the Spanish Falange, with its fascist ideology, was the dominant faction. The public interventions in the area of housing reflected the fight for political power through a fragmented public intervention, based on the creation of several parallel organizations with little coordination between them. Although housing was seen as a serious problem that needed to be addressed, it was not until 1957 that the Ministry of Housing was created with the capacity to unite and coordinate efforts.

In 1939, the Law of 19 April was enacted, defining the concept of ‘protected housing’ for the first time in Spain. This definition, however, applied only to the creation of housing for soldiers and ex-combatants to whom the regime felt indebted or for new government workers affiliated with the regime. That said, the new public approach to matters of architecture and housing had begun to take shape even before the end of the war. There were prominent architects among the leaders of the Falange, and they advocated a vision of the city and of housing that contrasted with the values the Modern Movement had begun to implement in the preceding decade. Following the establishment of the General Staff of the Nationalist faction, in 1938 the architect Pedro Muguruza was commissioned to reorganize Spanish architecture. In Burgos, the headquarters of Franco’s military command, Muguruza led a meeting of some 200 architects, sponsored by the Falange. The meeting laid out a reconstruction strategy and put forward the idea of ‘modest housing’. In his closing speech, the leader of the Falange, Raimundo Fernández Cuesta, defended the construction of ‘homes’, which he contrasted with ‘buildings’ and residential neighbourhoods. The home, the setting for family life, would be the constitutive element of the ‘new city of the Movimiento Nacional’. Working-class neighbourhoods were seen as problematic because they were understood as fostering class distinctions, and it was feared they would give rise to pockets of resistance against the regime. This appraisal was the expression of a more widespread desire to create a society freed from class struggles, in which the labour movement would be weakened and lose the ability to embrace ideologies that might lead to confrontation with the dominant classes.

The struggle for power among the political families of the winners of the war led to misgovernment, which Franco combatted through the Unification Decree, forcing fascists, traditionalists and monarchists to come to an understanding under a ‘single party’. At that point, the ‘Technical Services’ of the Regime were created, which included the architects affiliated with the Falange, under the continued direction of Pedro Muguruza. The members of the Technical Services were in charge of implementing the Reconstruction Plan which, de facto, continued to be led by the Falange, dominating other political factions.

Parallel to the creation of the Technical Services unit, other institutions were created with powers in matters of housing. In 1938, the National Service for Devastated Regions and Repairs was created, an organization dedicated to the reconstruction of ‘liberated areas’. At the end of the war, this body became part of the Ministry of the Interior and announced that all cities and neighbourhoods with a degree of destruction greater than 75% would be ‘adopted’ by Franco. This included the neighbourhoods in Madrid that had been fronts during the war. In 1939, a second General Directorate was created under the Ministry of the Interior – the General Directorate of Architecture – which was assigned to Pedro Muguruza, who continued to direct the Technical Services unit. The fourth body with powers in housing matters, created in 1939, was the National Housing Institute (NHI), under the auspices of the Ministry of Labour. It is not surprising that the existence of multiple bodies with overlapping powers gave rise to inefficiency.

Another example is the Madrid Reconstruction Board, an inter-ministerial body, in which the various other organizations participated, and which was managed in turns. The Madrid Urbanism Plan, drafted by Pedro Bidagor, was produced by this body, and the process of its approval was as complex as its development. Its application was slowed by the ongoing political struggles throughout the government structures, which became explicit in the heated debates about the possible segregation of working-class neighbourhoods. Congresses, assemblies and publications were organized for the sole purpose of staging the fight for power, in this case, through the debate on urban planning. To put it simply, the Falangist faction dominated by Muguruza promoted integration, while the defenders of the Plan Bigador were in favour of segregation, relying on the principles established in the Zuazo-Jansen Plan (1929) before the war.

Once the positions and the balance of power between the different organizations and institutions had been established, in the absence of a dedicated ministry, the Ministry of the Interior aimed to control Spanish architecture and the interventions in matters of public housing through the General Directorate of Devastated Regions and the General Directorate of Architecture.

The General Directorate of Architecture: Pedro Muguruza and Falangist Social Housing

The Falange spared no theoretical or informative efforts in defining what the regime’s ‘new architecture’ should be. The ideology of the Technical Services unit and its Reconstruction Plan is clearly expressed in the different dossiers and texts that have been published. Among the early manifestos, some of which date from before the end of the war, the most revealing content is contained in Chapter 5 of the first theoretical text on architecture and urban planning, which was published by the technical services, directed by Muguruza, entitled ‘Madrid Imperial Capital’. The aesthetic programme it promotes is clear and is based on a return to the ‘Empire’, with its architectural quintessence in the Escorial Monastery, the ‘cornice’ of the Royal Palace, and the Renaissance architecture of Juan de Villanueva and Juan de Herrera. Nostalgia for the imperial greatness of Spain also included a defence of the urban planning of the new cities in Latin America. Architecture was meant to be in the service of, and worthy of, a supposed ‘transcendent and universal mission’ for Spain. These principles were directly reflected by the architect Luís Gutiérrez Soto in his design for the Ministry of the Air in the Argüelles neighbourhood of Madrid.

The Ministry of the Air is the popular name for the General Headquarters of the Spanish Air and Space Force. The project was begun in 1943 by the architect Luís Gutierrez Soto but was not completed until 1958.

CC BY-SA 3.0.

The ideals of the Falange in matters of housing were widely reflected in these theoretical texts, although the opportunities to put them into practice were limited.

“As architects we can point out that, until now, we have built independent and distinct neighbourhoods for the different social classes, which naturally promotes and fuels the class struggle. Now, we wish to build neighbourhoods for people who are united by a common goal, and each of these neighbourhoods will include the entire hierarchy from the highest to the lowest.”

“We need not attempt to give a description of the dwelling, since a clear model is known to all, but we should emphasize the enormous breadth of this concept, since it includes everything from the home, as the heart of the family and the altar of tradition, to the home as a working tool”.

Quotes from the magazine Reconstrucción, cited in LÓPEZ DÍAZ, Jesús, “Vivienda Social y Falange. Ideario y construcciones en la década de los 40”. In Scripta Nova, revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencia Sociales de la Universidad de Barcelona, 2003. The article includes several quotes from the magazine Reconstrucción, published by the General Directorate of Devastated Regions between 1940 and 1956.

The home must, therefore, respond to the following organizational principles: the bedrooms for the children must be separated by sex, and the parents’ bedroom must be independent. There must be a room that ‘symbolizes the idea of home’. The home must provide the adequate conditions of hygiene, and its appearance should reflect the characteristics of the traditional architecture of each region.

We have already commented that Pedro Muguruza began amassing a growing amount of power when he was named as the head of the General Directorate of Architecture – without leaving the Technical Services department, which was incorporated, de facto, under his direction. Muguruza’s vision of housing and urban planning can be seen in places like Cerro de Palomeras in Vallecas, the first design for a settlement presented by the regime.

In this neighbourhood model, all social classes are to be mixed and the materialistic vision of housing – i.e., responding to the free market – is set aside to make it possible to effectively influence the social composition of the neighbourhoods:

“We would prefer to achieve the ideal of an absolute hierarchy in the settlement as a whole, with the nature of a brotherhood, a big social family; in conjunction with support from those who provide a nuance of Spanish tradition to the new area along with their social rank.”

Pedro Muguruza, transcription of a lecture given in 1941.

Cerro de Palomeras, known as ‘Las Palomeras’, in an image from 1970. The neighbourhood was demolished at the point when it had been designated substandard housing, in the framework of an urban planning project that covered the entire Puente de Vallecas area, between the 1970s and 1980s..

Image from the feature on the Palomeras neighbourhood by the photographer Andrés Palomino, 1976. Rainy Day in Las Palomeras.

Image from the feature on the Palomeras neighbourhood by the photographer Andrés Palomino, 1977: Snow and Mud.

In accordance with the Falangist ideology, Cerro de Palomeras – since demolished – was made up mostly of single-family homes; large residential blocks were avoided as much as possible because they were understood as referencing socialist imagery. In addition, the neighbourhood was given a nostalgic and rural air: homes with pens for livestock that mimicked vernacular architecture, without any trace of modernity in the architectural language. The neighbourhood was made up of 15,000 homes, grouped into four cores with shared services, including the offices of the political authorities and the church. To increase its capacity, four multi-family blocks permitted, which the future users built themselves under the supervision of the administration’s architects. Although, evidently, the direction and inspiration of the settlement came from Muguruza, the project was signed by Ramiro Avendaño Paisán and Luis Díaz-Guerra Milla.

After Las Palomeras came the towns of Colonia Tercio y Terol, La Ventilla, the emergency shelter in Usera/Colonia Almendrales, and the vaulted houses in Usera. Of all these, only the Tercio y Terol colony is still standing. These neighbourhoods ended up suffering from the poor quality of the construction and the materials used, and from the fact that they represented a low-density growth model that would become obsolete with the capital’s expansion.

The so-called vaulted houses in Usera, by the architect Luis Moya, are of the most architectural interest. In this case, despite the modest materials, there is a real reflection on structure, based on a series of load-bearing walls and Catalan-style brick vaults on different levels. On the façade plane, a series of perpendicular walls act as buttresses. In some of Moya’s works, we find traits of modernity; such is the case of this building, now demolished, where there seems to be a desire to combine a rural or vernacular imagery with the coherence, order and powerful volumes typical of modern architecture – an avenue of formal exploration that will be seen broadly in the towns built by the National Institute of Colonization.

“Casas abovedadas en el barrio de Usera construidas por la Dirección General de Arquitectura. Arquitecto: Luís Moya”, Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 14, February 1943.

The construction solutions tested in Usera were reused in the residential duplex building in the Colonia Virgen del Pilar by Francisco de Asís Cabrero Torres-Quevedo, who built it as director of the Obra Sindical del Hogar, which will be discussed later.

In the Colonia Virgen del Pilar building, the expressivity of the structural elements, like the buttresses, is even more pronounced and intensified by the scale: three duplex units stacked vertically – in other words, a total of six floors. The typology is a classic duplex with access via a corridor: the entrance level with the kitchen that ventilates to the corridor and the living room; and the top level with three bedrooms and a bathroom.

Duplex residential building in the Colonia Virgen del Pilar by Francisco de Asís Cabrero Torres-Quevedo.

© Fundación Docomomo Ibérico/Susana Landrove.

© Archivo Servicio Histórico COAM

The actions of the General Directorate of Housing were not limited to the city of Madrid. Its interventions can be traced in the Bulletin of the General Directorate of Architecture, which the organization published from 1941 to 1943 and from 1946 to 1957, the year the Ministry of Housing was created, under the name Bulletin de Información de la Dirección General de Arquitectura. With a strong ideological underpinning, the bulletins addressed all the areas of architectural creation, including social housing.

The results of the initial actions by the General Directorate of Architecture were unsatisfactory even in the eyes of the people responsible for them. In 1945, Muguruza referred to the new neighbourhoods as ‘suburbs’ and described the few constructions as a ‘limited partial attempt’. The initial idea of the Falangist city was diluted when it collided with reality, and the neighbourhood model that aimed to move beyond social classes, expressed so vehemently on paper, was unconvincing in its materialization. Ultimately, the Falange did not find an answer to the question that had been central at the end of the war: how to house the growing number of working class families that were arriving in cities without creating spaces that might fuel the rise of class consciousness and its possible politicization.

The General Directorate of Devastated Regions

During the early years of Franco’s regime, two General Directorates coexisted in the Ministry of the Interior’s organization chart: the aforementioned General Directorate of Architecture and the General Directorate of Devastated Regions, the aim of which was to reconstruct properties that had been damaged during the war. In 1951, its function was considered to have been completed and it became part of the General Directorate of Architecture.

Devastated Regions, initially directed by the civil engineer José Moreno Torres, shared its functions with the Municipal Reconstruction Boards. In the case of Madrid, the actions within the urban centre fell under municipal purview, while interventions in the neighbourhoods along the periphery, including the construction of new settlements, corresponded to Devastated Regions. In some cases, especially in the case of new neighbourhoods, Regions served as the executing arm of the General Directorate of Architecture, which established the urban model. It was also their responsibility to repair infrastructure, particularly roads and bridges. We should not forget that Devastated Regions took advantage of the forced labour of Republican political prisoners, which it labelled ‘Worker Battalions’.

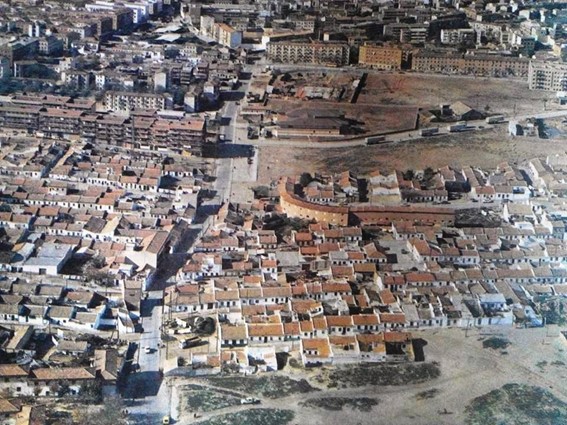

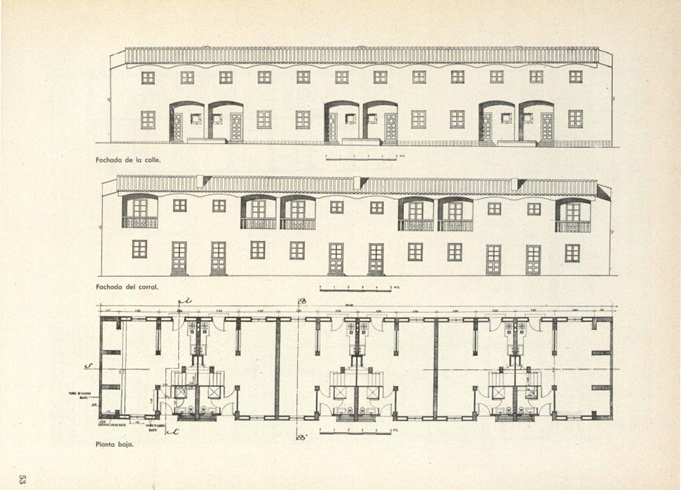

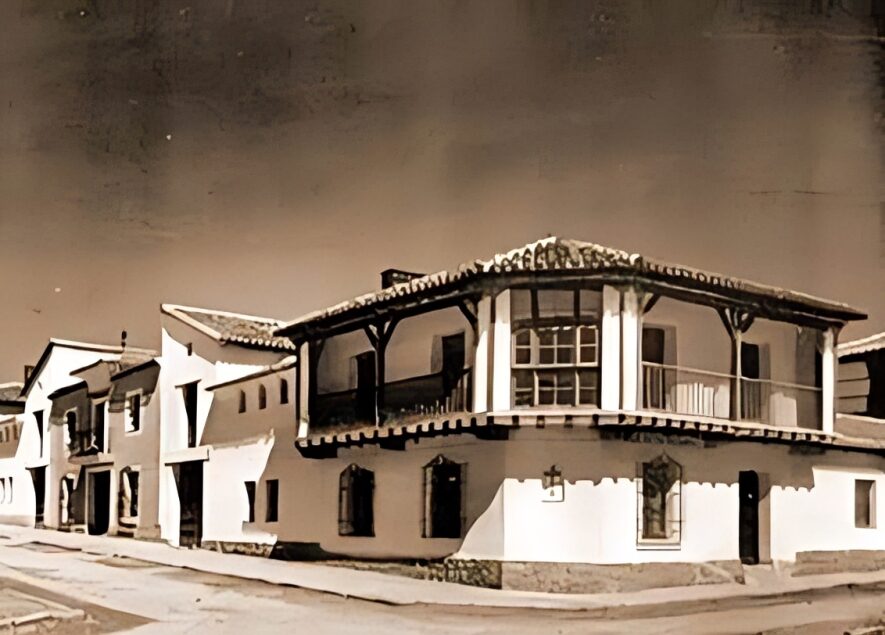

Regions’ actions began with the reconstruction of damaged buildings or infrastructures, in cases where this was possible. Where the destruction was too severe, temporary shelters were built for the homeless while permanent housing was being completed. Of all the neighbourhoods built by Devastated Regions, the one in Almería ─ called ‘Regiones Devastadas’ after the developing organization ─ is one of the best known, probably due to the eclecticism of its architecture, which gives it a picturesque and cinematographic character. This neighbourhood, dating from 1944, was the first experiment by José Luís Fernández del Amo ─ in this case, together with Francisco Prieto Moreno and Carlos Fernández de Castro ─ in which he investigated the limits of tradition and architectural modernity in the construction of urban areas. Fernández del Amo continued to develop this formal research in the towns of the National Institute of Colonization – discussed later in this text – achieving results of an extraordinary quality and beauty. In the case of the Almería neighbourhood, there is still a clear lack of formal definition that can be seen in the contrasting series of direct architectural references: architecture from Ceuta, the baroque of western Andalusia, etc. Likewise, the paradigmatic white walls in the more symbolic buildings are combined with a studied display of colour in the residential buildings and their courtyards. In the early years, these features were used as a backdrop for several Hollywood films.

A postcard of the Regiones Devastadas neighbourhood in Almería ─ now known as ‘Regiones’. The urban structure of the neighbourhood has been preserved, but the private buildings have undergone severe alterations, preventing its perception in a unitary way..

Vintage photograph of the Regiones Devastadas neighbourhood in Almería ─ now known as ‘Regiones’. The urban structure of the neighbourhood has been preserved, but the private buildings have undergone severe alterations, preventing its perception in a unitary way.

Partial model of the Regiones neighbourhood in Almería built for the exhibition ‘Campo cerrado: Art and Power in Post-war Spain’ at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2016.

In Madrid, several neighbourhoods were developed by Devastated Regions, for example, the homes in Puerta de Toledo (by Felipe Díez Somarriba) and the low-income homes in Carabanchel Bajo (by Luís García de la Rasilla following a design by Emiliano Amann). Amann’s memoir perfectly captures the tension after the war and how it transferred into the programme in residential architecture:

“Naturally, we have did not even remotely consider, for a single moment, adopting Marxist solutions based on designing living rooms that could be converted into bedrooms at night, so anti-Christian in their lack of moral values and so poorly suited to families.”

The projects for Colonias de Nuestra Señora del Carmen and Casas Baratas Barrio Goya were developed and carried out by the internal services of the directorate of Devastated Regions and served as a model for the reconstruction of entire towns like Brunete and Belchite or Porcuna in Jaén. Although these were new towns, their character unabashedly mimicked the local traditional architecture.

Image of the reconstruction of the town of Brunete. View of a street, 1946.

Image of the reconstruction of the town of Brunete. Main square and Casa del Partido [Party Headquarters] (current town hall), 1946.

The National Housing Institute (NHI): Incentivizing the Private Development of Affordable Housing

On 19 April 1939, just two weeks after the end of the Spanish Civil War, the National Housing Institute was created, dependent first on the Trade Union Organization and, later, (as of 2 January 1942) on the Ministry of Labour. Federico Mayo was initially named as director. The same decree that created the Institute contained the first definition of ‘protected housing’ in Spain.

The Institute was created under the auspices of the Ministry of Trade Union Action and Organization, although it had its own, independent legal status to manage its resources. Years later it was put under the purview of the Trade Union Organization ─ known as the Sindicato Vertical ─ then, subsequently, the Ministry of Labour, and finally it was affiliated with the Ministry of Housing once it that body was created in 1957. Like the Ley Salmón under the Republican government, the legislation and scope of the NHI did not encompass the direct development of housing; it did, however, include the definition of living standards, the determination of the criteria for granting aid and benefits, as well as designating the responsibility for inspections. To provide more detail:

“Its mission will be to dictate building standards, select housing types and materials, organize and orient the initiatives of construction companies, and contribute to the construction of low-income housing by granting certain benefits, ensuring that they address, first and foremost, the needs of the least fortunate and that the homes meet the most rigorous conditions for hygiene and construction quality, without the State taking responsibility for the financing, the construction, or even the direct administration of the works, notwithstanding their responsibility to ensure and intervene effectively to facilitate and guarantee that all these functions are carried out in the best possible way and serving the social purpose that must be paramount in this great undertaking.”

Census Guide to the Archives of Spain and Latin America of the Ministry of Culture.

Perhaps the responsibility of the NHI that had the most impact on the development of social housing in Spain was its ability to

“propose, by region, the types of housing that should serve as a model, identifying their characteristics, depending on whether they are for farmers, artisans, etc, and providing the blueprints and models free of charge; these models can be selected via public competitions and awarded cash prizes along with diplomas or medals.”

Ibíd.

As we have seen in previous sections, the Falange held positions of power during the early years of Franco’s rule and also directed the new organizations that dealt with housing, including the NHI. This explains why the plaques that identify the buildings adhering to the Institute’s criteria, having received the associated benefits, display the yoke and arrows, the symbol of the Falange. Until the recent passage of new legislation regarding historical memory, it was very common to see these plaques on buildings throughout Spain.

Identification plaque for buildings that met the characteristics and therefore benefited from aid from the National Housing Institute.

The actions of the NHI during the 1940s were not precisely effective: a lack of resources ─ both economic and material, a lack of coordination between the different organizations with responsibilities in matters of housing, and a small and inefficient structure in the institution itself resulted in very limited results during the first decade of its existence. Despite the broad powers allocated to the Institute, it would not be correct to claim it had any widespread influence on the introduction of typologies intended to be serialized. And yet, nearly all the relevant achievements in social housing, most dating from the early 1950s, received some of its benefits.

In Barcelona, the social housing for fishermen developed by the National Housing Institute, together with another building also in the Barceloneta neighbourhood built five years later, represented the starting point for José Antonio Coderch’s brilliant research in the area of multi-family housing. In Madrid, the highlight was the residential building for José Fernández Rodríguez, designed by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza. These works all date from the early 1950s and clearly show a departure from the Falangist postulates in matters of housing and a return to modernity in Spanish architecture.

The first of these designs, more in line with our understanding of social housing today, is an aggregation that forms a complete U-shaped block. The central courtyard is surrounded by volumes running perpendicular to the street, which subdivide and qualify the space into smaller areas more suited to a domestic atmosphere. Each staircase serves three homes per floor, which take the form of a star: two parallel to the interior façade and one in the volume that juts out. However, through a masterful distribution, Coderch made sure that all the living rooms and their terraces open toward the interior of the block. The programme is rounded out with three double bedrooms of a limited size, plus a bathroom, laundry room and kitchen.

Grupo Almirante Cervera, housing for fishermen by José Antonio Coderch de Sentmenat and Manuel Valls Vergés. Barcelona 1950-1960.

The other two buildings are inserted into consolidated urban areas, with the particularity that they both occupy a corner. The first has three open façades, and the second forms an ‘L’ with one façade facing the street and one facing the interior of the block. The programme in both buildings is similar ─ in terms of size and the number and use of the rooms ─ as it had emerged as typical of social housing at the time.

Residential building for José Fernández Rodríguez, Francisco Javier Saénz de Oíza, Madrid 1949-1955.

Housing in Barceloneta, José Antonio Coderch de Sentmenat and Manuel Valls Vergés, Barcelona 1951-1954.

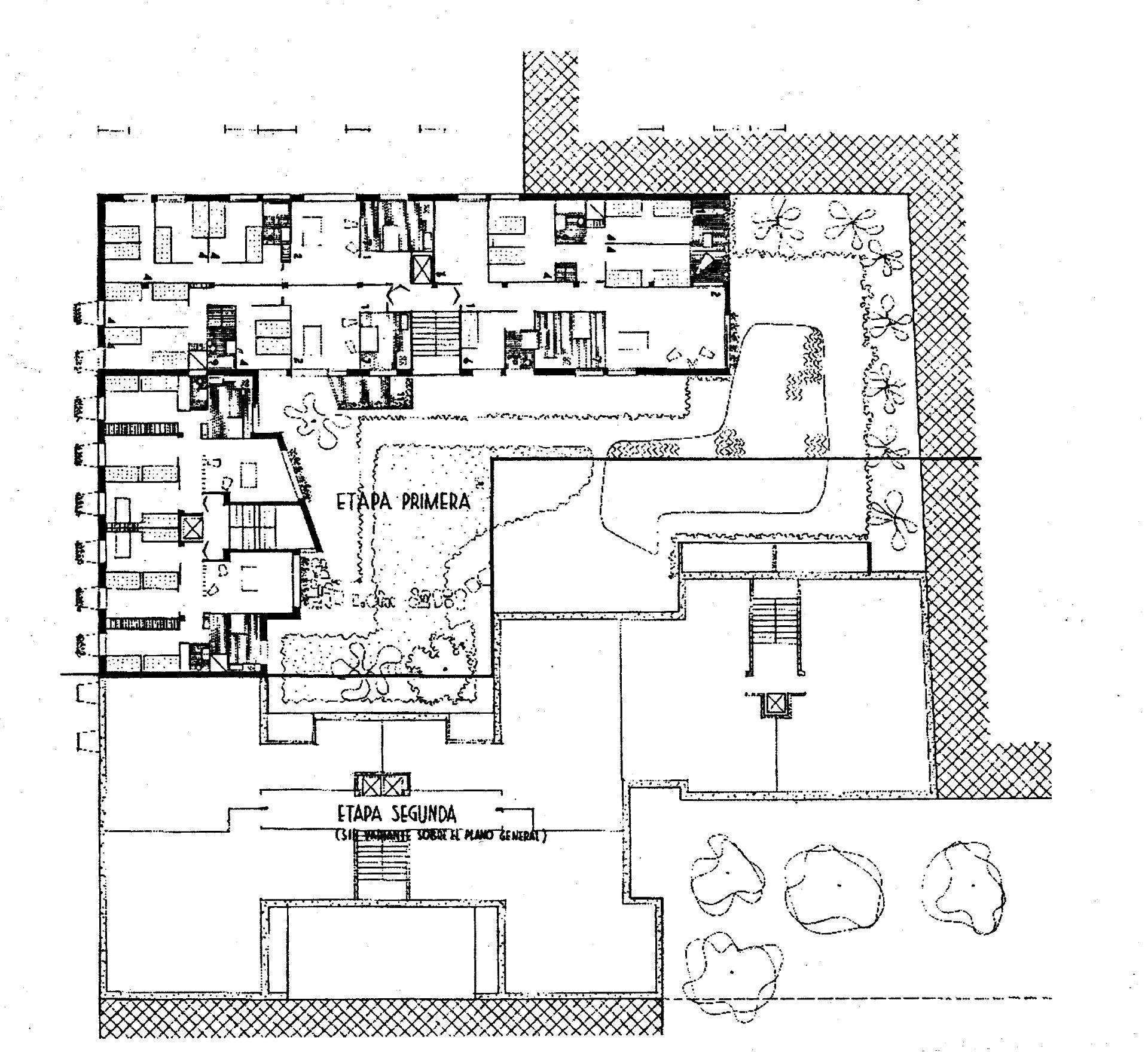

In the mid-1950s, the return to Modern Movement principles was evident in the volumetric organization of small urban fragments, such as the block containing the Escorial Residential Complex in Barcelona. This complex is one of the first projects in post-war architecture that offered an alternative arrangement to the closed city block. It was built a year after the foundation of Grup R and was designed by a series of architects who became members of that collective. Grup R sought to bring Catalan architecture back into line with the postulates of the Modern Movement and to reconnect with the avant-garde currents of European architecture after the interruption caused by the Spanish Civil War. In an absolutely clear way, its aesthetics mark a return to the urban and architectural principles the GATPAC had promoted during the years of the Republic. The Escorial Residential Complex is formed by two ‘L’-shaped blocks with exterior galleries and a taller, rectangular tower, with the vertical communications core as a free-standing volume. Two basic typologies are combined in the ‘L’-shaped buildings, reproducing the typical three-room programme of bedroom, kitchen-laundry room, and bathroom-living room, in this case with an additional WC. In the tower, the units are accessed via a corridor and are configured as duplexes facing both the front and rear façades, with four bedrooms on the upper floor and the more public areas on the lower floor. Both typologies have large outdoor terraces. The series of built volumes surrounds an interior space with gardens and some shared services.

Three types of housing from the Escorial Residential Complex, 1952-1962, Barcelona, Antoni Perpiñà Sebrià, Francesc Mitjans Miró, Josep Alemany Barris, Josep Maria Martorell Codina, Josep Maria Rias Casas, Manel Ribas Piera and Oriol Bohigas Guardiola..

The private development of affordable housing accelerated significantly in the 1950s, and there are numerous interesting examples from that period. The urban model that began to prevail moved away from the Falange’s ideas of low-density neighbourhoods, instead tackling the housing problem with neighbourhoods that espoused Corbusier’s urbanism based on open volumes as contrasting with growth through expansion neighbourhoods.

The Obra Sindical del Hogar – OSH (Department of Housing)

The Obra Sindical del Hogar was one of the institutions created during the Spanish Civil War and in the early years of Franco’s regime. As we have seen, it coexisted in a disorderly and inefficient way with other organizations until the creation of the Ministry of Housing, which rationalized and clarified the separation of powers between the different institutions; in the case of the OSH, its integration into the Ministry did not entail its dissolution. In the beginning, it was dependent on the National Delegation of Trade Unions which, in turn, fell under the auspices of the Ministry of the Interior. More than an organization, it emerged as a plan of action – as expressed by the word obra, or work, in the name – which communicated the new orientation and purpose which Franco’s regime intended to give to the Trade Unions: an organization intended to improve quality of life for workers, without sparking a class struggle or fuelling class consciousness. We should remember that, due to this new orientation, the unions in Francoist Spain were not independent bodies. They were official organizations directly controlled by the State and membership was mandatory: any worker, by the sole virtue of that condition, became a member of the Single Union. Within the Union Organization, whose mission was ‘the moral and material elevation of workers’, there were several departments with different functions ranging from education and leisure to the promotion of health and access to housing. The function of the OSH, therefore, was to build housing on land it had purchased or expropriated for the members of the Trade Union Organization – that is, for all workers – although the developments were also made accessible to ex-combatants, members of the Movement, widows of soldiers killed in combat, etc.

Through 1960, but above all in the 1950s, the OSH built some 140,000 homes, generally grouped into neighbourhoods. As was the case for other organizations, its actions were governed by an action plan: the ‘Francisco Franco Housing Plan’ of 1945, which was later updated on two occasions. The first OSH plan set a goal to develop 20,000 newly built homes per year, with quotas for each province decided by the Central Trade Union Board. One important aspect to consider about the actions of the OSH is that, once the developments were completed, the organization remained responsible for their management. Residential buildings were governed by a structure that was an extension of the union organization: what were called Neighbourhood Councils. The ownership model was also unique, since the units were awarded on the based of an amortization model, with small monthly payments that included maintenance of the building and the surrounding neighbourhood. At the end of the amortization period, beneficiaries were allowed access to full ownership of the units. However, many of these developments showed serious construction and structural problems even before the amortization period ended.

“In association with the Housing Institute, cooperatives, city councils, provincial councils and other para-governmental organization or professional bodies looked after the interests of their employees, members, or associates. Residential blocks, garden cities, and neighbourhoods began to emerge for workers in specific sectors of the economy or government employees. With this constant construction, the so-called middle class benefited not only as tenants in rental accommodations, but also as owners of the homes they lived in, as we will see later.

As for the workers, the day labourers, the modest producers who could not afford to buy property for themselves, the National Delegation of Unions advocated for them with radical enthusiasm.

Beginning from the enactment of the Law of ‘39, the Unions, through their National Delegation, were in turn given an ongoing and sacred task: providing each worker with a home to call ‘their own’. In other words, elevating the proletariat to the middle class.

The Obra Sindical del Hogar was created for this purpose; once it had been organized across all 50 provinces and provided with funding, it began its operations in January 1941. An analysis of its operations should prove interesting. The headquarters are in Madrid, with a delegation in each of the provincial capitals. Architects, administrative experts and a legion of quantity surveyors intervene at each location following approval of the plans and blueprints sent from the places where there was a need for new housing. The beneficiaries, the workers, obtain ‘their’ houses according to this system: they contribute 10 percent of the price (and if they are unable, the Delegation provides an advance), through a ‘home savings account’, which is opened for them by the savings bank in their municipality. Any budget surpluses are deposited, plus the interest on the account, in addition to a contribution from the Delegation of Unions (45 million annually). Once the request from the beneficiary is accepted by the Provincial Delegation, construction on the house can begin. The State exempts them from paying contributions for 20 years and reduces the payment of any tax (real rights, etc.) by 90%. Immediately, the National Housing Institute advances the remaining 90% of the cost of the house to round out the total. And the tenant can repay the total price over the span of 40 years (at monthly amounts ranging between 92 pesetas and 178 pesetas monthly for the first 20 years, and 87 and 168 for the last 20) to become the absolute owner. If they leave the house during the rental-payment period, they are refunded the money they have contributed. It should be noted that these rent payments made by the beneficiary are much lower than the cost of the rent on a privately owned house, in addition to the fact that the houses built by the Obra are infinitely more beautiful, luxurious and suited to each group of professions: farmers, fishermen, factory workers, miners, etc.”

Article by Tomás Borrás from La Vanguardia Española, which appeared under the title ‘The Obra Sindical del Hogar greatly expands the number of Spanish homes’

The need for the purchase or expropriation of land by the OSH led to dubious decisions regarding the location of the interventions: for example, in marshland in the Llobregat Delta in the case of the San Cosme Neighbourhood Absorption Unit (UVA) in El Prat de Llobregat, Barcelona. In these developments, we begin to see neighbourhoods that evoke the collective idea of the residential estate: newly built neighbourhoods that are isolated, or at least disconnected, from the urban fabric, with an open layout of rectangular blocks characterized by uninspiring and repetitive architecture and low-quality construction. Some of these developments were called UVAs (Unidades Vecinales de Absorción, or Neighbourhood Absorption Units), a figure that the NHI had also used in its 1955 Plan, alternatively called Absorption Settlements or Directed Settlements. As we have seen in previous sections, the figure of the UVA permitted a certain degree of experimentation, as was the case in the Experimental Colony of Villaverde Alto in Madrid. In fact, the OSH acted as a construction company by direct delegation of the NHI.

We have seen how the NHI’s first direct plans focused on the Madrid area. This was not the case with the OSH, where the developments were spread across Spain in a distribution that depended on the number of workers and the strength of each Provincial Council. In Catalonia, along with the aforementioned San Cosme neighbourhood, the OSH developed the San Roque estates in Badalona and the Verdum neighbourhood (or Cases del Governador) in Barcelona. Both estates have been infamous for the accumulation of construction and social conflicts over the years. But not all OSH actions were affected by precarious conditions or low construction quality.

“As far as the homes themselves are concerned, the level of quality is uneven. In isolated cases, there is an acceptable level of constructive quality and standards. However, the large estates (those with more than 500 homes), which encompass 36,000 dwellings, equivalent to 90% of the total in the province, show serious construction deficiencies and problems with conservation in the majority. The total absence of maintenance in these cases aggravates the situation and leads to accelerated material deterioration and a rapid degradation of living conditions.”

JUBERT, Juan, “Editorial“, Quaderns d’arquitectura i Urbanisme 105, Barcelona, 1974.

In Valladolid and Zamora, for example, there are two developments that show notable constructive and aesthetic quality, despite being located on the urban periphery. Both are works by Jesús Carrasco-Muñoz Pérez de Isla and, in them, we find references to the Siedlungs of Red Vienna and, especially, Karl Marx Hof. The chosen volumetric arrangement, with its long shallow built volumes, results in flats that open onto both façades, with all the rooms facing an exterior and with optimal conditions in terms of ventilation and sunlight. The presence of storage areas in all the rooms is also an example of the architect’s dedication to providing comfortable and quality homes.

Homes for the Obra Sindical del Hogar in Zamora and Valladolid by Jesús Carrasco-Muñoz Pérez de Isla (1937-1942) © Fundación Docomomo Ibérico

The 1950s: From Directed Settlements to the Creation of the Ministry of Housing (1957)

As we commented above, in the 1950s there was an awareness of the true scope of the housing problem in large cities and an acceptance of the evidence that the initiatives of the previous decade had not addressed the problem in its entirety. On 16 July 1955, a Decree Law was passed that laid out the regulations for the execution of the National Plan for Limited Income Housing and established the economic means for its funding. Once again, this framework aimed to address the development of public housing, establishing principles that shifted away from Falangist postulates. The articles in the decree make it clear that, despite the word ‘national’ in the name, its primary objective was to address the problem in the city of Madrid. The first article dictates ‘that the economic means be allocated for the implementation of the “limited income” housing plan in the municipality of Madrid’. In summary, the decree authorized the Urban Planning Commission to purchase land and develop it, through public credit. To make this possible, another decree was issued the previous year giving the National Housing Institute, among other public organizations, the power to develop housing directly, thus expanding on its founding powers.

El Plan de 1955, en su llevada a la práctica en Madrid, concede la capacidad de autoconstrucción de las viviendas de baja altura a los propietarios, siempre bajo la tutela de los técnicos del Ayuntamiento y de los arquitectos de la época. Por esta razón, estos nuevos barrios se conocerían como “Poblados Dirigidos” o “Poblados de Absorción” y se llegaron a construir hasta siete en la periferia de Madrid. Con ellos, el INV pretendía dar una respuesta urgente y económicamente viable a la llegada de migrantes del campo a la ciudad de Madrid, que no paraba de acelerarse.

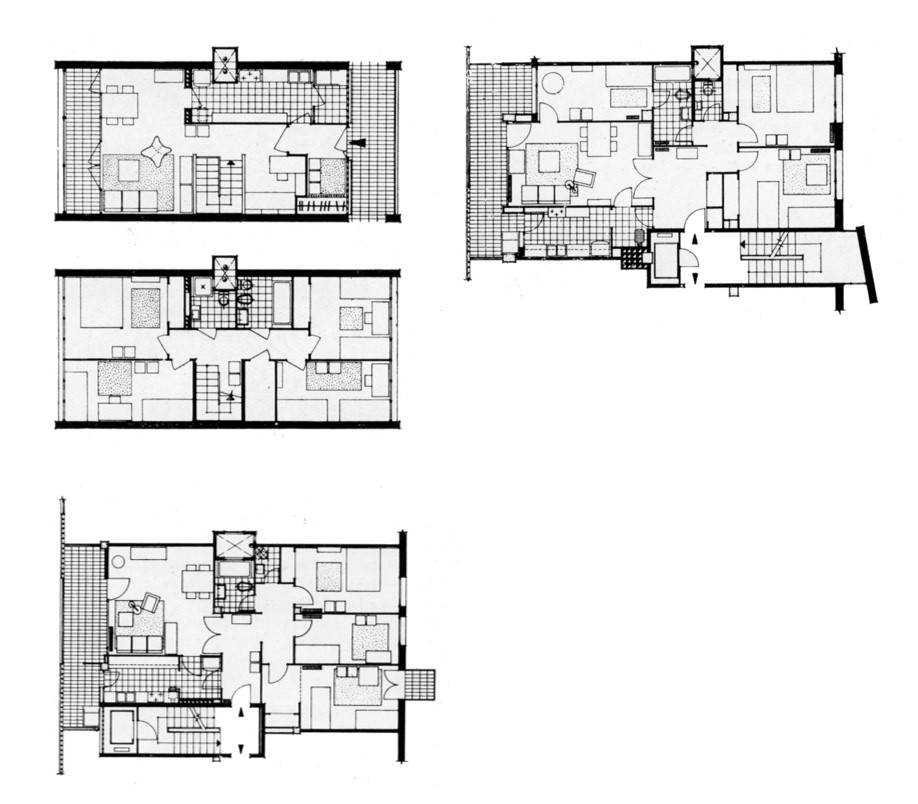

The first of the settlements, built between 1956 and 1959, was Entrevías by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, Jaime de Alvear Criado and Manuel Sierra Nava. It was intended to absorb the population that had settled in shanty towns. The homes, in this case, are minimal in size ─ 60 m2 ─ and the construction quality is conditioned by a very tight budget and by the need for future inhabitants to be able to continue the construction themselves. Despite these limitations, the architects proposed an exercise in systematization and modulation that is of undeniable architectural interest.

The commission for the design of this new neighbourhood, on the site where a slum had cropped up, and for the corresponding infrastructure and buildings was given to the young architects Sáenz de Oíza and Jaime de Alvear, the former recently arrived from a short stay in the United States and the latter with ties to social activism in Madrid’s periphery. The design provides a quick, simple and brilliant response, derived from a careful analysis of the economic, administrative and time-based difficulties. The complex is based, almost in its entirety, on a single housing typology which, due to its strict modulation within a square plot, can be extended like a blanket, with no limitations. A general systematic organization of the urban space – streets and squares – and a layout of the residential blocks are derived from this module and its aggregation, supporting the configuration of the urban space and fostering hygiene in both the outdoor spaces and the interiors of the homes. The design is rounded out with a clear-cut insertion of the complex and its corresponding connections with the rest of the sector. The project was conceived so it could be built by people with minimal experience and limited means, by the same population that had occupied the previous self-built settlement.

Recent experiences such as those of Alejandro Aravena, with several self-built neighbourhoods in Latin America, are based on approaches similar to those applied in the directed settlements: when the problem of peripheral settlements is too great compared to the administration’s economic and logistical resources and its experience, the administration can still take action by improving conditions in those settlements through the acquisition and division of land, the delimitation of public spaces and the implementation of the minimum necessary infrastructures and services. The attention these new projects have garnered, especially from the younger generations of architects, reveals a generalized lack of familiarity with the experiments that took place in the mid-20th century both in Spain and in Latin America, which employed even more radical approaches.

Poblado Dirigido de Entrevías, 1956-1959, Madrid, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, Jaime de Alvear Criado, Manuel Sierra Nava

By 1950, the Regime had become aware that the housing actions that had been carried out during the previous decade were insufficient to alleviate the housing deficit. The forecasts for population growth and urban concentration demanded much more effective measures. The government, which had set the goal of balancing the number of homes with the number of existing families, was facing an immediate deficit of one million homes in 1950. With the improvement of economic conditions and the end of the shortage of materials, a growing number of interventions took place in a variety of areas, undertaken by the scattered organizations under the leadership of the NHI, but also – and as a novelty – from the private sphere, which showed a new interest in the development of protected housing.

In Barcelona, the celebration of the Eucharistic Congress inspired a group of Catholic industrialists and financiers, grouped together in the Catholic Association of Leaders (1951), and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, to finance and develop a new neighbourhood, which came to be known as El Congrès. Residents were also encouraged to participate in the development process, through the establishment of quotas of 100,000 pesetas. The NHI recognized the group as a Charitable Organization-Developer of Protected Housing, endorsing its founding principles and giving it the power to act as a proxy or by delegation. Construction began in 1953, and the final costs were much higher than expected, with the expansion of the project in both its size and scope.

Viviendas del Congreso Eucarístico, 1952-1961, Barcelona, Carles Marqués, Josep Maria Soteras Mauri, Toni Pineda

While in the 1940s, 1 million people had abandoned their rural lives to move to the big city, between 1951 and 1960, 2.3 million people did the same, only to be faced with a harsh reality in large cities: a rise in the number of informal settlements, newly built neighbourhoods that suffered from rapid physical and social degradation, etc. The authorities could not ignore the evidence that, with their meagre actions following the end of the war, they were creating precisely what they had hoped to avoid: pockets of poverty and marginalization that could become seeds of opposition to the regime. Given these poor results and the realization that, as the regime began to open up and the economy improved, the problem of urban housing would take on a scope that had been previously unknown, a change of course was urgently needed. New legislative measures and many more resources were mobilized but, for those actions to be effective, the absurd offshooting of official bodies with overlapping powers had to be remedied. Thus it was decided to finally address the problem through a new Ministry to centralize all the actions, resources and powers in matters of housing, with the architect José Luís Arrese, from Bilbao, serving as the first minister of the sector in Spain.

Bibliography

BUSTOS JUEZ, Carlota, La obra de Pedro Muguruza: breve repaso de una amplia trayectoria en P+C 05, 2014, pp.101-120.

PÉREZ-ESCOLANO, Víctor, “Arquitectura y política en España a través del Boletín de la Dirección General de Arquitectura (1946-1957)”, in RA: revista de arquitectura 15, 2013, pp. 35-46.

CÁNOVAS, Andrés, ESPEGEL, Carmen, DE LAPUERTA, José Maria, MARTÍNEZ ARROYO, Carmen, PEMJEAN, Rodrigo, Vivienda Colectiva en España. Siglo XX (1929-1992), Biblioteca TC, Valencia, 2013.

CAZORLA SÁNCHEZ, Antonio, Fear and Progress: Ordinary lives in Franco’s Spain 1939-1975, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2009.

AZPILICUETA ASTARLOA, Enrique, La construcción de la Arquitectura de Postguerra en España (1939-1962), PHD Tesis, 2004.

LÓPEZ DÍAZ, Jesús, Vivienda Social y Falange. Ideario y construcciones en la década de los 40 en Scripta Nova, revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencia Sociales de la Universidad de Barcelona, 2003.

“La remodelación de Palomeras en Arquitectura”, en Arquitectura 242, May-June 1983, pp. 13-17.

JUBERT, Juan, “La O.S.H. : características de la gestión de la Obra Sindical del Hogar, La OSH y la política de vivienda : la política de vivienda del estado y la OSH una cronología paralela”, in Quaderns d’arquitectura i Urbanisme 105, Barcelona, 1974.