Introduction and Origins

The Barcelona School refers to a group of Catalan architects whose work demonstrates a series of coherent characteristics, beginning in 1965 and continuing through the mid-1970s.

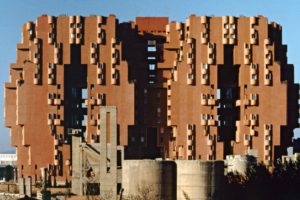

Unlike other groups in the architectural avant-garde, such as the GATPAC, the Barcelona School was never a formal or consolidated group, nor was it associated with a foundational text or manifesto. The existence of a “Barcelona School” is ultimately a bit of an invention – in other words, it is a critical reading or interpretation of the reality of the architectural production that took place in Catalonia during a certain period of time. As a result, it was not a closed group, nor did the members engage in any type of formal affiliation. While the list of members cannot be considered complete or exhaustive, the following studios and architects are often associated with the Barcelona School: Federico Correa, Alfons Milà, Studio PER (formed by Lluís Clotet, Pep Bonet, Christian Cirici and Óscar Tusquets) Gabriel Mora, Helio Piñón and Albert Viaplana, the Taller de Arquitectura led by Ricardo Bofill, MBM (Oriol Bohigas, Josep Martorell and David Mackay), Lluís Cantallops, Ramon Maria Puig, Leandre Sabater, Lluís Nadal, Vicenç Bonet, Pere Puigdefàbregues, Enric Tous and Josep Maria Fargas.

Oriol Bohigas was responsible for the initial definition of the group and the characteristics that make it possible for the architectural production to be read as a unit: in a 1968 article in the journal Arquitectura (number 113-114), published by the Architects’ Association of Madrid, Bohigas defines the work of his own studio and ties it in with that of other contemporary Catalan firms. Bohigas himself warns of the impossibility of providing a simple description, since the definition of “common” characteristics is intermingled with the defence of a particular way of understanding and practicing architecture. In that sense, he offers a description of general features that can be identified as “unifying coincidences” and “common characteristics”, and which are, in turn, a mixture of circumstances and evaluative aspects that associate architectural production with more generalised features of Catalan culture at the time.

Model of the “Compacte de l’Ametlla”, a series of 12 chalets designed by Studio PER. The image of this model was included in Oriol Bohigas’s article “A Possible Barcelona School”, from 1968.

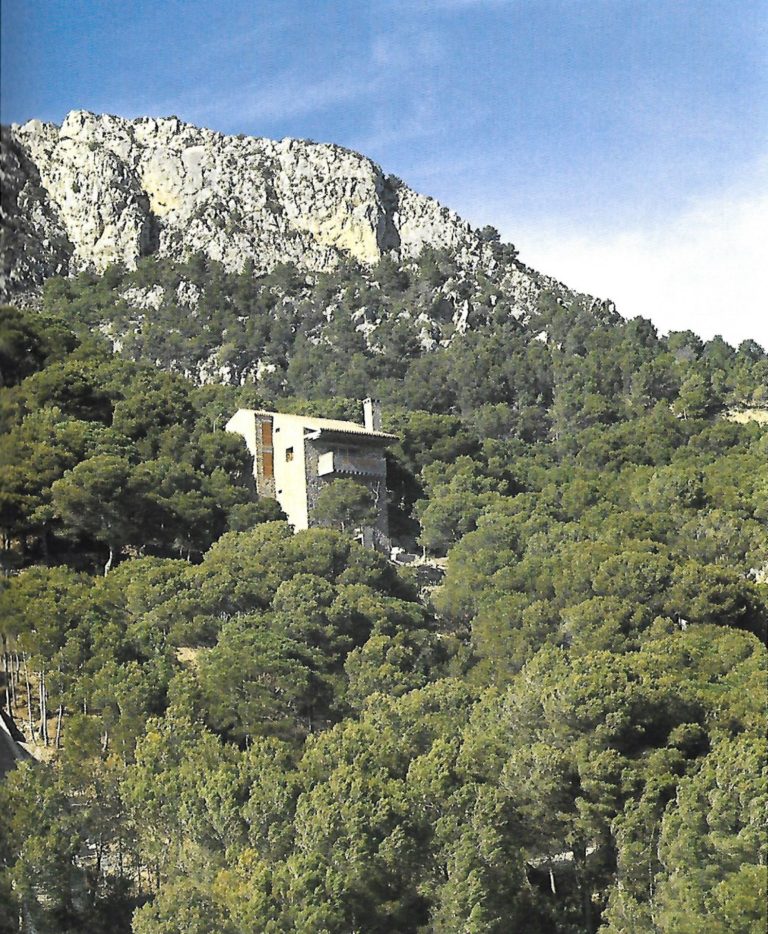

Bohigas sets himself somewhat apart from the previous generation and, although he was once a member of Grup R, through the definition of the Barcelona School he manages to distance himself and associate his architecture with that of a younger generation, farther removed from the climate of the post-war period and more open to new political and cultural values. In this way, Bohigas also underwrites a generational transfer in Catalan architecture, with his own firm serving as the bridge to support the transition away from the more abstract rationalism of Grup R toward a new avenue intended to link up with the most avant-garde architectural production of the time on an international scale. However, although the production of Grup R was waning by the end of the 1960s, there are clear traits in its production that would later be attributed to the Barcelona School, such as its emphasis on Mediterranean culture and popular architecture.

International Connections

From an international perspective, Bohigas associates this architecture with that of the Milan school of the time and emphasises the influence of Federico Correa on a generation of Catalan architects through his role as a professor at the Barcelona School of Architecture. Beyond their architecture, according to Bohigas, the architects from the Barcelona School are characterised by a consistent cultural stance and by their defence of culture as a defining aspect in their professional activity, to the extent that many of them also worked in other cultural expressions aside from architecture. This interest also drove their desire to form part of broader European and international cultural movements.

The period following the Second World War brought urban difficulties that were very similar in many large European cities, but each country offered a different response. While northern countries turned toward solutions for the housing problem based on technology, very much in line with the postulates of the modern movement, Mediterranean countries, and Italy in particular, relied much more on traditional construction techniques. In the case of Italy, a brilliant generation of architects looked at the limitation of resources as an opportunity to reflect on the construction tradition in the Mediterranean. In Italy, new cities weren’t built; instead, in many cases, existing cities were enlarged and their neighbourhoods were updated. These actions were carried out by the public body in charge of reconstruction, INA-Casa, and by a group of architects that included, among others, Mario Ridolfi, Saverio Muratori, Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Gio Ponti, Adalberto Libera, Giancarlo de Carlo, Mario de Renzi, Ludovico Quaroni, Giuseppe Samonà, Gino Valle and Vittorio Gregotti. This extraordinary generation achieved very compelling results with very limited resources, with the goal of rebuilding and modernising traditional residential fabrics both from the point of view of the physical configuration of the city, as well as its image and its social fabric. At the same time, there was a boom in new filmmakers who portrayed these urban realities under the name of Neorealism – a name that was eventually also adopted to define the architectural movement. The profound architectural reflections that accompanied this work had broad international repercussions due to the appearance of new specialised publications such as Domus and Casabella that served as their loudspeaker.

The Tiburtino neighbourhood in Rome by Mario Ridolfi and Ludovico Quaroni, built by INA-Casa in the 1950s. The Tiburtino neighbourhood is usually associated with Italian architectural neorealism.

With a great sense of timing and obvious ideological and contextual coincidences, Bohigas defined the “Barcelona School” as a local reflection of the climate that existed in Italy. Likewise, the coordinated reading of Catalan architecture in the form of a “group” or “school” attracted and facilitated the attention of specialised magazines that confirmed and legitimised the existence of this “supposed Barcelona School”. In short, the characteristic features of Italian neorealism were essentially the same as those used to define the School of Barcelona: a rationalist constructive language, a reflection on the Mediterranean and on the role of tradition and popular knowledge in architecture, and a lasting interest in design.

Modernity and Tradition

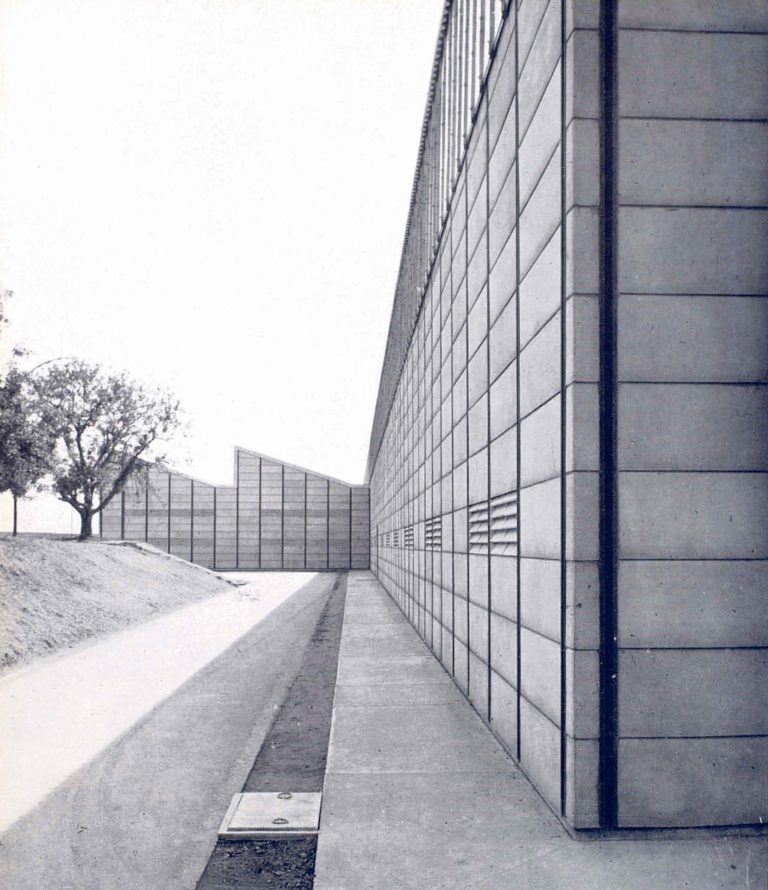

The first feature common to the architects of the Barcelona School, according to Bohigas, has a clear political and economic underpinning: the difficulty for Catalan architects in accessing the large-scale commissions developed by the public authorities or large corporations. Their production, as a result, was constrained to a very limited typology of commissions, subject to marked economic limitations and constrained by the interests of the developers. Bohigas explains that these economic constraints also translate into the need to use construction techniques in keeping with the criteria of practicality, where there is little room for technology understood as innovation. The architecture, consequently, has to serve collective needs as opposed to making an impression or engaging in personal experimentation. Making a virtue of necessity, the possibilities of traditional construction techniques are harnessed to the fullest extent, while the designs are always determined by the constraints of the brief and the context.

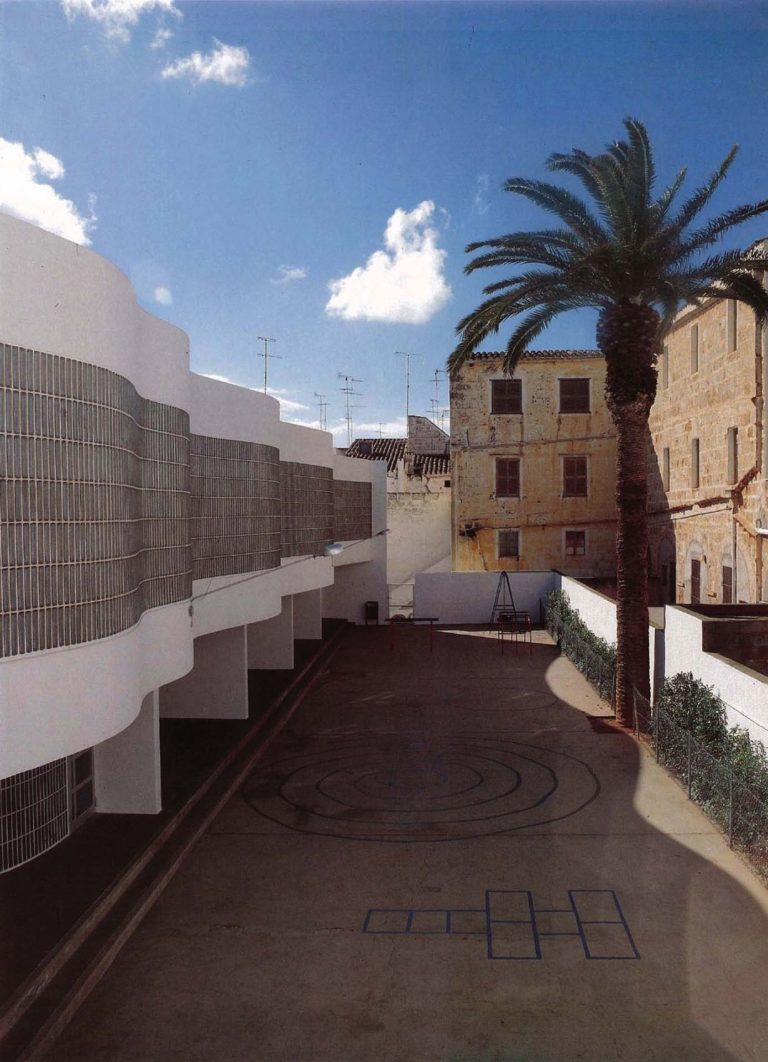

In this architecture that he aspires to define, Bohigas highlights a current that picks up on rationalism and is not exempt from a moral underpinning. According to him, the constraints described above lead to “very closely following in the footsteps of the most strictly rationalist tradition.” This occurs in an international context in which rationalism has been reduced to the pursuit of a “Cubist plasticity”. The architecture of the Barcelona School, on the other hand, shows a resistance to “an analysis rooted in a serious and profound rationalist method” – that is, one governed by logic. Paradoxically, the chain of logical decisions that guide the designs clearly distance the final result from the formal purity that is typical of rationalism: the complications that emerge in any design, the expression of needs, and the “accidents” in the construction techniques, along with their “honest expression” are combined with an “avant-garde approach” that, in short, transforms the abstraction typical of rationalism into figuration or even into “language”.

Touching precisely on the idea of “architectural language”, Bohigas makes reference to Umberto Eco’s work – which had such an influence on the architects of the Milan School – and which was “imported” by Lluís Clotet in an article in the magazine Destino. The argument is clear: “Architecture, like any activity, is a purely an issue of communication” and, therefore, it is born as a response to contextual or environmental circumstances (social, economic, sociological, technological, etc.). Architecture can – and, according to Bohigas, should – transform those circumstances into collectively recognised communication “codes”. Consequently, language – understood as a “series of shared forms everyone can recognise” is legitimate and necessary in architecture.

La Casa del Pati, a multi-family residential building in the Guinardó neighbourhood of Barcelona, designed by MBM in 1962, which combines a concrete structure with traditional materials and construction techniques.

The relevance of the architecture of the Barcelona School comes from its ability to explore new fields of expression and because it is an open and evolving architecture. Its representatives adopt an avant-garde approach, and in their work they have the ability to predict, test and “push” the formal codes characteristic of the architecture of their time towards new avenues of expression. This is made possible through intimate knowledge of the society they are serving, moving away from purely utopian theses or simple historicist mimesis. In this sense, the architecture of the Barcelona School stands apart from other contemporary architectural experiences that address the issue of language because of “a certain taste for critical perspectives, for irony, for basically and even openly cynical attitudes” and a predilection for architecture that may be “of little prestige, debilitated, dramatic and transitional”.

In short, Bohigas concludes that, for all the above reasons, “the work by these architects is obviously not equivalent, nor are their methods identical, nor could they be confused in a serious analysis, but they are all part of a formal current, such that, when seen together and contrasted with other works that are more geographically and mentally remote, they offer the semblance of a certain style”. Moreover, this fact is augmented or fuelled by the close personal relationships that existed between this group of architects.

Legacy

The architecture of the Barcelona School emerged toward the end of Francoism, but it laid the ideological and formal foundations for the profound urban transformations of the 1980s, which became possible due to the resurgence of democracy and the recovery of the local and regional public administrations’ investment capacity.

The representatives of the Barcelona School soon began taking over the teaching positions and the leadership of design departments left vacant by the previous generation. Bohigas himself became dean of the School of Architecture, making sure the principles and values of the Barcelona School could be passed on to the new generations. When Bohigas was appointed as the head of urban planning for the Barcelona City Council, the policy he helped introduce translated many of the principles of the Barcelona School onto a larger scale. The major players who had been a part of the movement were entrusted with making it a reality, while incorporating the new generations of architects who had been Bohigas’s students (as is the case of Enric Miralles).

It is impossible to understand the astounding architectural climate of pre-Olympic Barcelona and the great international attention and admiration it attracted, without the foundations that had been laid by the Barcelona School in the previous decade. In that sense, the Barcelona School was a true school: a space for collective reflection and generational transmission and continuity, both in the academic sphere and in architecture studios that maintained a traditional organization based on a learning structure involving teachers and disciples. The Barcelona School also helped foster an ecosystem of small and medium-sized firms, in which the organization was never based entirely on business criteria or corporate structures but rather founded on personal rapport and relationships.

Bibliography

CANOVAS, Andrés, GARRIDO, Ginés, BOHIGAS, Oriol, “Una posible Escuela de Barcelona”, en GARRIDO, Ginés, CÁNOVAS, Andrés, eds., Textos de crítica de arquitectura comentados 1, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Departamento de Proyectos, Madrid, 2003, pp. 358-367.

AA VV, Art de Catalunya. Urbanisme, arquitectura civil i industrial, Edicions L’Isard, Barcelona, 1998.

BOHIGAS, Oriol, “Una posible ‘escuela de Barcelona”, en Arquitectura: revista del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid 118, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid, Madrid, 1968, pp. 24-30.

BOHIGAS, Oriol, “Para la definición de una Escuela de Barcelona II”, en Jano: arquitectura, decoración y humanidades 48, Barcelona, June 1977, pp. 49-51.

BOHIGAS, Oriol, “Una Posible Escuela de Barcelona”, en Nueva Forma 83, Madrid, Decembre 1972, pp. 22-23, 28.

BOHIGAS, Oriol, “Una Posible Escuela de Barcelona”, en Architettura 9, January 1970, pp. 582-591.