The Cultural Construction of the Mountains

Before the 19th century, interest in the mountains was largely military and productive ─ mining, timber, coal, livestock, etc. In the early 19th century, however, a powerful imaginary around the mountains began to emerge in the cultural sphere, which was joined by a scientific interest. In Germany, this renewed interest in the scientific exploration of the world was associated with one name: Alexander Humboldt. Although Humboldt is not a well-known figure in Spain, his influence in the German-speaking and Anglo-Saxon worlds and in Latin America was paramount. Humboldt was responsible for the first ‘ordering’ or grouping of nature into coherent families, which became the foundation for all subsequent knowledge of the plant and animal kingdoms. Most certainly, without Humboldt’s vast amounts of research, Darwin’s theories would never have been taken seriously beyond the scientific community. Humboldt realized that there were a series of orders in the plant world that were stratified in height, and which were comparable all over the planet. His work and his theories were the conclusions of his scientific voyages, especially to South America, where he climbed some of the highest peaks, recording all kinds of data and collecting thousands of biological samples. Before embarking on his first trip to South America, where he completed his legendary ascent of Chimborazo in 1802, he sailed to Tenerife where he was the first person to climb Mount Teide for scientific pursuits. After Humboldt, mountaineering took on a scientific character and spread across the world. In the Canary Islands, the Humboldt expedition was vital in publicizing not only the existence of the archipelago, but also the enormous importance of its ecosystems. Today, Humboldt’s work offers us further evidence of global warming.

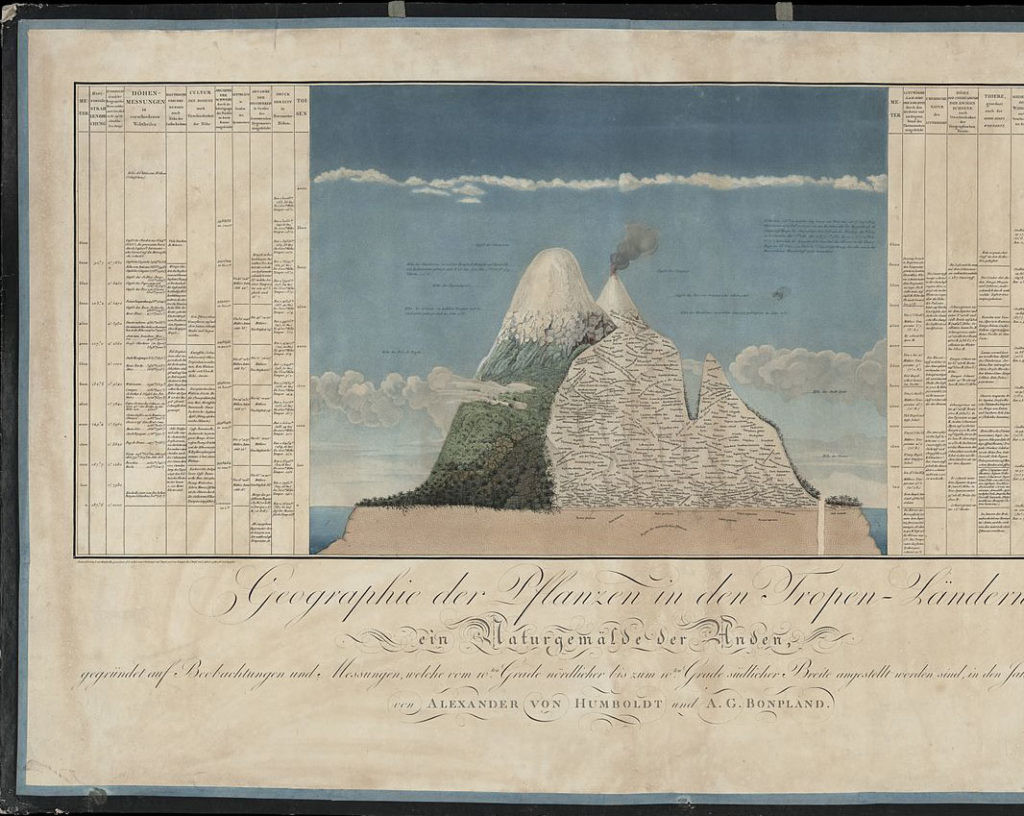

Cross-section of Chimborazo by Alexander von Humboldt. It details the plant species, ordered by altitude: mushrooms and palm trees on the lower elevations; oaks and ferns in the middle zone; lichens on the borders of the snowy areas, etc. It was the first time that an attempt was made to depict the relationship between climate and life in a comprehensive way..

In the Iberian Peninsula, the first scientific expeditions, such as those of Puig i Cadafalch, were cultural in nature: with the appearance of nationalisms, this political and cultural climate had to be backed up by history – especially medieval history. In Spain, the story of the Reconquista played a fundamental role. From a cultural standpoint, there was a focus on the remote mountain areas that become the repository for a culture that had resisted the Muslim invasion: this was the case in Ripoll, the Vall de Boí, Roncesvalles, Covadonga, etc. The mountains on the Cantabrian coast and the Pyrenees were home to the vestiges of those historical moments replete with epic and legend.

Around the same time, hiking groups were cropping up across the Spanish territory, and literature was contributing to the creation of the mystique associated with the mountains: Rousseau, Thomas Mann and Goethe set some of their novels on mountain tops; Verdaguer and Maragall, in Catalonia, made the mountains the main theme of some of their epic poems; Vicente Aleixandre, Luis Rosales and Antonio Machado evoked the mountains as a setting and as a metaphor. The construction of the imaginary of the mountains also took on a moral overtone: in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in Wagner’s opera Parsifal or in the play Terra Baixa by Ángel Guimerà, the mountains are a place of essences, of rugged characters, but also of nobility and ancestral worth, in contrast with the flatlands, equated with the city and defined as a place of hypocrisy, vanity and a tepidness of character.

In architecture, the mountains also served as a metaphor for the creation of a bright, utopian architecture. In the imagination of Bruno Taut, Alpine Architektur was sparked by the profound impact of the First World War. He advocated architecture as a means to attain a mysticism and spirituality that would banish warmongering forever from the hearts of men. To bring it to life, he situated his architectures in communion with the peaks, gathering the entire tradition of the moral construction of the mountains together with glass as a symbol of purity. His drawings and concepts offered an alternative to the budding utilitarian rationalism in the form of a mystical and soulful expressionism.

Bruno Taut, Die Statdkrone [The City Crown], 1919.

Pilgrimage Routes

Even before the mountains took on a scientific or cultural interest, people travelled through mountainous areas along pilgrimage routes. In Spain, the Camino de Santiago (The Way of Saint James) is the most significant of the European pilgrimage routes. Its existence is justified by two apparently unconnected facts. On the one hand, it was upheld by the legend of the European epic of Saint James the Great, who, according to Christian traditions, ended his days in Iria Flavia, in present-day Galicia, where he was secretly buried. On the other, when the mandatory pilgrimage routes for Christians to the Holy Land were made impassable by the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem, the route to Saint James’s tomb, in one of the most remote places on the continent, emerged as an alternative.

From the outset, the success of the Camino de Santiago drove an incipient urban development in towns located along the pilgrimage route through the mountains on the Cantabrian and Asturian coastline. This unexpected vector of development demanded infrastructures that would open the territories to visitors walking through: hostels, sanctuaries and places of worship or monasteries began to crop up. In the 20th century, the places along the route began accumulating buildings that provided services or shelter. In León, the Sanctuary of the Virgen del Camino and the associated Dominican convent, was fully renovated by Fray Coello de Portugal in one of the most relevant works of modern religious architecture in Spain. In 1954, the team, including Francisco Javier Sáenz Oiza, José Luis Romany and Jorge Oteiza, won the National Architecture Award for their proposal for ‘a Chapel on the Camino de Santiago’ that was never built, but had a notable influence due to its radicality.

‘A Chapel on the Camino de Santiago’ by Francisco Javier Sáenz Oiza, José Luis Romany and Jorge Oteiza. National Architecture Award 1954.

The Camino de Santiago is not the only relevant Spanish pilgrimage route that has given rise to important architecture. The Ignatian Way, currently being recovered for the celebration of its 500th anniversary, recalls the route taken by Saint Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order, from his birthplace in Azpeitia to the Catalan town of Manresa, where he lived as a hermit in what is known as the Cova de Sant Ignasi. One of the most impressive works of Spanish religious architecture would be inexplicable without the existence of this pilgrimage route. It is the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Aránzazu, which was rebuilt by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza and Luis Laorga after the original basilica was destroyed by fire. A young generation of Basque artists worked on it, including Oteiza, who became emblematic of Basque culture in subsequent years. The spectacular church, perched on a cliff, is surprising for its strength and grandeur, despite being located in a remote area in the mountains of Guipúzcoa.

“The natural surroundings and the idiosyncrasy of the pilgrims visiting the basilica made it necessary to avoid soft external forms like the ones from the previous church. Consequently, the building needed to have an austere and robust appearance, like the mountains that surround it. The materials used are stone and wood for the cladding and concrete for the structure”. Jesús Martín Ruiz, excerpt from the Docomomo Ibérico Fiche.

Basilica of Our Lady of Aránzazu by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and Luis Laorga Gutiérrez (1950-1955) in Oñate, Guipúzcoa. Source: © Jesús Martín Ruíz/Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico.

Mountaineering and Hiking in Spain

As we have seen, at the end of the 19th century, an imaginary surrounding mountaineering emerged that extended beyond the sphere of ethnography. The idea of climbing mountains as an interior journey and, to an extent, a moral conquest was preceded by new aesthetic concepts like the exaltation of ‘sublime beauty’ – described, in the early 19th century in the philosophical writings of Edmund Burke and in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. Immanuel Kant also described it unequivocally: life is an effort to climb the slope by which matter descends. In Germany, Switzerland and Austria, countries at the forefront of mountaineering, a large amount of literature associated mountain climbing with the development of a profound philosophical idealism.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich, 1818 (public domain).

In Spain, the popularization of mountaineering occurred well into the 20th century, when clubs and associations dedicated to the activity began to appear, such as the Spanish Alpine Club, founded in 1904 by Manuel González de Amezúa, Cayetano Vivanco and Francisco del Río, the Club of Twelve Friends (1913) and the Peñalara Royal Spanish Mountaineering Society (1915). With the rise of mountaineering, new infrastructures were required since climbing complex summits demanded base camps to provide supplies at the start of the ascent. Networks of mountain lodges began appearing in many areas of the Peninsula to serve as supports for mountaineering activities.

The network of mountain huts in the Pyrenees was a response to this need: increasingly experienced and daring climbers were beginning to depart from the usual ascent routes to set themselves new challenges. The first refuges, called ‘mountain hospitals’ were built in France, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees. One of the first in Spain was the Vielha Hospital or Sant Nicolau refuge, in the Vall d’Aran. It was followed by the hospital in Benasque and the one at the source of the Ter River in Girona. Franco had a mountain residence built for himself, copying the alpine chalet typology, in what would be the first national park in Spain: Aigüestortes i l’Estany de Sant Maurici (Lleida). However, the limitations regarding construction materials and the existence of a strong imaginary of what the architecture of a mountain refuge should be obstructed any true modern typological investigation, and the image was always tinged with the picturesque quality associated with the imaginary of alpine or high-mountain constructions.

Xalet de Catllaràs, La Pobla de Segur, Lleida, Antoni Gaudí, 1902.

With the popularization of private vehicles, people’s interest in Sunday outings and children’s summer camps also grew. Cars offered a ‘low-intensity’ approach to enjoying the mountains, which prompted the emergence of small-scale tourist infrastructures like picnic areas, overlooks and restaurants. In Lanzarote, César Manrique built his famous El Río Overlook on the impressive cliff that runs along the channel that separates Lanzarote from La Graciosa, called El Río. With the aim of equipping the Timamfaya National Park for hiking, Manrique crowned a small volcanic cone – one of the many that dot the park – with a visitor centre and a restaurant called El Diablo where they cook using geothermal heat.

The mountains near large cities like Madrid became weekend leisure destinations. In Cercedilla, the Las Berceas lathhouse covers a series of pools fed with water from the Venta River.

Facilities for school groups or lodgings built by companies for their employees’ recreation also gave rise to buildings in which the architectural language of the mountains – a nod to popular and rural architecture, with the use of wood and stone, and sloping roofs – was combined with the functionality characteristic of the time. Such is the case of the children’s camp in Canyamars by MBM (Martorell, Bohigas, Mackay, 1961-1965), in the Serra de Marina (Maresme, Barcelona), which they highlighted as an emblematic work of Group R.

Summer camp in Canyamar, Dosrius, Barcelona. MBM architects 1961-1965. Today it is known as the Mas Silvestre Hostel and continues to host school groups.

Source: Hostel website

Tourism Reaches the Mountains: Spas, Skiing and Summer Holidays

In Spain, mass tourism in the mountains is much less popular than coastal tourism. The emergence of both, in the 19th century, was associated with or justified by the pursuit of health and was aimed at the wealthier classes. Surprisingly, one of the first tourist attractions in the country were spas, and the reason for visiting them was therapeutic.

The first modern spa project dates back to the reign of Charles III in La Isabela (Guadalajara). The monarch even spent time enjoying the waters himself, convinced of the benefits. In 1816, during the reign of Ferdinand VII, the first Regulation on Waters and Mineral Baths was drafted. It was followed by others that regulated the intervention of certified doctors with authority in matters concerning spas.

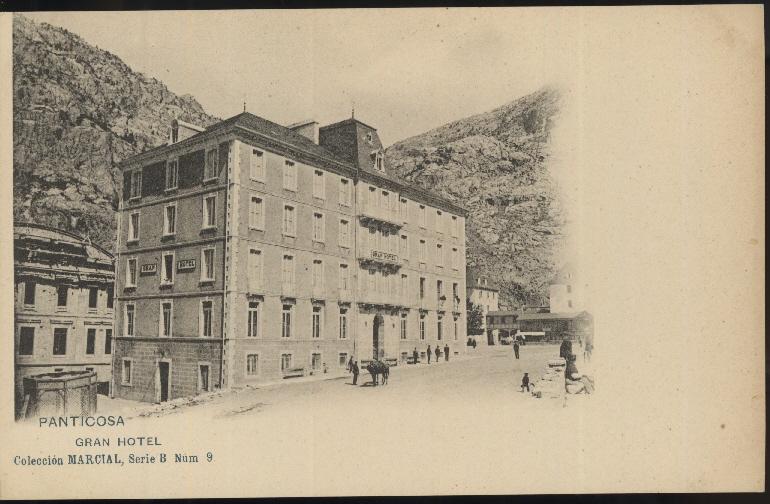

Throughout the 19th century, important tourist centres focused on hot springs were built in Europe in Vichy and Baden-Baden. In Spain there was no comparable network of spas, but, in the mid-19th century, (proto)tourism around hot springs drew some 80,000 bathers countrywide, and the aristocracy (imitating royalty) became the first clients. The expansion of the railway drove the creation of spas and the first hotels in places that were once remote and unreachable. In 1892, there were 152 operating spas, which received some 150,000 visitors. By that time, it was no longer just sick people who visited by medical prescription; spas were beginning to be associated with new concepts like wellness and rest. The Gran Hotel de Panticosa, designed by the architect Pedro Candau, and the Vichy Catalan complex in Caldes de Malavella (Girona) were the pioneers of spa tourism in Spain at the turn of the century.

Gran Hotel de Panticosa

Source: Ministry of Health and Sports, Online Collections.

Vichy Catalan Spa in Caldes de Malavella, Catalonia. CC BY 3.0

With the change in orientation from health to leisure, spas began to incorporate new services like dance halls, casinos, music kiosks and restaurants. The Casino de La Toja (1905) was perhaps the most emblematic of them all, and the nearby intervention in the pavilion of La Fuente de Gándara by the architect Antonio Palacios (1920) became one of the most successful examples of spa architecture in the country. Unfortunately, during the 20th century, spa tourism fell on hard times, and there are no rationalist spas that are truly relevant in the country.

La Fuente de Gándara by the architect Antonio Palacios (1920) near the Mondariz Hotel and Spa, Pontevedra.

Source Turismo de Galicia

The other – and perhaps the most relevant – activity that promoted the tourist development of the mountains in Spain was skiing. The first Spanish skiers were self-taught young people from Candanchú. Immediately other groups imitated them in the Sierra Nevada and the Navacerrada, creating their own ‘clubs’. The opening of the Canfranc train station at the end of the 1920s paved the way for the first Spanish ski resort to be founded in 1928, also in Candanchú. The resort included lodgings and the first rudimentary infrastructures that facilitated the mechanized ascent of hills and the maintenance of skiable slopes that were signposted, free of vegetation and safe (later called runs).

In the 1940s, the construction of hydraulic infrastructures meant that transportation also improved and the traditional isolation of the mountains began to abate. A clear example is the construction of the Canfranc hydroelectric power station, which led to improvements in infrastructure and helped popularize skiing among the urban population. Fisac participated in the construction of the plant and left behind, in Candanchú, a delicate building that reinterprets vernacular Pyrenean architecture: the Parish Church of Nuestra Señora del Pilar.

Furthermore, during the Spanish Civil War, skiing became an important activity for both sides, who had soldiers in military ski units. After the war, specifically in 1941, the Spanish Ski Federation was created, which fostered the growth of the sport in the country. At the end of the 1940s, the second ski resort was opened in the Navacerrada Pass, Madrid. In the 1970s, skiing was already quite popular among Madrid’s residents: as many as 130 coaches and 8,000 private vehicles ─ some 40,000 people ─ were counted in a single weekend.

A similar development occurred in other parts of Spain, the Aragonese and Catalan Pyrenees, the Sierra Nevada in Granada, Leitariegos in León and Valdezcaray in La Rioja. At the end of the 1940s, the first Catalan ski resort, La Molina, opened, which also had the first chairlift in the Spanish state. Little by little, as the ski areas were equipped with new infrastructures like ski lifts, chairlifts and cable cars, the practice of the sport became much more accessible and, consequently, the number of enthusiasts grew. But these new means of transport also provided easier access to high mountain areas and encouraged hiking and climbing. In the Picos de Europa, the architect Ángel Hernández Morales and the engineer José Calavera Ruiz, built the lower station of the cable car in Fuente Dé, which also houses the mechanisms, an example of the many transport infrastructures that were built in the almost 40 ski areas in the country.

The real popularization of skiing came at the end of the 1970s, and especially during the 1980s. The first ski area prepared for a massive influx of skiers, and which was also understood as a comprehensive tourist experience, was a personal project by the Catalan architect and businessman Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich in La Masella (La Cerdanya, Girona). The business model was complemented by the sale of chalets and apartments. The largest ski resorts, like Baqueira-Beret in the Vall d’Aran, were accompanied by major real estate developments that forever changed the landscape of nearby mountain regions. A real estate boom took place in La Cerdanya, for example, with the improvement of infrastructures providing access. Projects like the block of flats in La Molina, by F. Joan Barba Corsini, or the hotels in Formigal, by Teodoro Ríos Usón, and in Puigcerdà by Josep Maria Sostres, provide a measure of the intensity of the tourist development in some mountain areas, which recalled the widespread urbanization that took hold in seafront areas along the Spanish coastline.

Flats in La Molina, Alp (Girona), 1963-1969, Francesc Joan Barba Corsini.

‘Mountain’ Architecture

It wasn’t just strictly mountain towns that experienced this new development: housing developments for second homes cropped up along the mobility corridors between large cities and the mountain regions. Some of these developments, like Passeig Maristany in Camprodón, were developed in the early decades of the 20th century, building on the idea of the garden city imported from England. But it was the popularization of the private vehicle that led to a veritable boom in suburban architecture among people hoping to escape the city. The mountains, in some cases without any urban development infrastructure and owing to limited regulation on the part of the authorities of the regime, were occupied by illegal housing estates, a serious problem that has continued into the present in many parts of Spain. These unlicensed developments – either illegal or unregulated in terms of urban planning – are a problem all along the Spanish Mediterranean coast and in some inland provinces. Today, many of them have become primary residences. Not only is it difficult to provide them with the minimum urban services, but their existence generates unwanted flows of mobility and dangerous situations in the case of natural disasters like fires. In Catalonia alone, of the existing 1,433 housing estates, there are 607 with deficits derived from a situation of illegality or lack of regulation, most of which are on mountain slopes.

In both planned and unplanned developments, the architectural expression of the constructions often responded to the desire to represent themselves as ‘non-urban’ architecture. Many of them resorted to the use of pitched roofs and a vernacular or traditional imaginary. In addition to the pitched roofs, the use of materials like wood or natural stone and the introduction of elements like external shutters and eaves ended up shaping the imaginary of ‘mountain architecture’.

In general, in mountain areas, modern architecture adopted elements that were understood to be alien to the formal repertoire of rationalism, like pitched roofs. This is the case of the house for Maria Teresa Campañá Xampeny by Josep Maria Sostres in Ribes de Freser, or the Olano or Ballvé houses by Coderch (in Comillas and Camprodón), nearly the only ones where a pitched roof is used for expressive purposes.

On the Cantabrian coast, especially in the Basque Country and Cantabria, the occupation of the mountains was a necessity due to the scarcity of flat land for urban development. In these cases, architectural elements were also used to contextualize the constructions: in Peñarrubia, Cantabria, the housing in la Hermida by Ignacio Álvarez Castelao or the Olazábal and Aizeztu residences, in Mutriku, both by Peña Ganchegui, respond to that aim.

Today, rising temperatures and the scarcity of snow are endangering the economic model in many mountain areas. Activities like rural tourism are unlikely to attract the massive influx of visitors generated by skiing, and it will be necessary to reflect on the economic viability of large areas that, at the same time, are slowly emptying of people. The abandonment of rural territories, including mountain areas, (the so-called ‘empty Spain’) has become the subject of political and social debate.

Bibliography

- PEÑA RUBIO, Ignacio de la, Arquitectura y montaña. Estudio de los métodos de construcción de la Arquitectura de Alta Montaña y su entorno, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 2021.

- DEL MOLINO, Sergio, La España Vacía, viaje por un país que nunca fue, Turner Noema, Madrid, 2020.

- COLOMINAS FERRAN, Joaquim, “Josep Puig i Cadafalch i la Mancomunitat de Catalunya”, in Empremtes d’història 4, Diputació de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2019.

- GARCÍA BRAÑA, Celestino, GÓMEZ AGUSTÍ, Carlos, LANDROVE, Susana, PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, eds., Arquitectura del movimiento moderno en España. Revisión del Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edificios del Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, / Arquitectura do Movimento Moderno em Espanha, Revisão do Registo DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edifícios do Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Arquia, Barcelona,

- MANRIQUE, César, Lanzarote, arquitectura inédita, Cabildo Insular de Lanzarote, Lanzarote, 2019.

- WULF, Andrea, La invención de la naturaleza: El Nuevo Mundo de Alexander von Humboldt, Taurus, Penguin Random House, Madrid, 2016.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos II: Ocio, comercio, transporte y turismo, 1925-1965, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2011.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos I: Lugares públicos y nuevos programas, 1925-1965, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2010.

- CENTELLAS, Miguel, JORDÁ, Carmen, LANDROVE, Susana, eds., La vivienda moderna, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2009.

- PUERTAS, Javier, Historia del turismo en España del siglo XX, Síntesis, Madrid, 2007.

- AA VV, Santuario de la Virgen del Camino, T6 Ediciones, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, 2006.

- MANN, Thomas, La montaña mágica, EDHASA, Barcelona, 2005.

- SÁNCHEZ FERRÉ, Josep, “Historia de los Balnearios en España. Arquitectura, patrimonio, sociedad”, in LÓPEZ GETA, Juan Antonio, PINUAGA ESPEJEL, J.L., Panorama actual de las aguas minerales y minero-medicinales en España, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Madrid, 2000.

- MONFORTE GARCIA, Isabel, Arantzazu Arquitectura para una vanguardia, Diputación Foral de Guipúzcoa, San Sebastián, 1994.

- SOLÀ MORALES, Ignasi, FABRÉ, Xavier, BARBAT, Andreu, Arquitectura balnearia a Catalunya, Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1986.

- MUÑÓZ, Ramón, Historia del montañismo en España, Author’s Edition, Madrid, 1981.