Industrialization on the Spanish Northern Atlantic area

Although the first hub of industrialisation in Spain was in Catalonia with the growth of the textile industry, the Spanish Northern Atlantic area soon joined this process, in this case, driven by its significant natural resources, especially iron ore. A conservative mentality among the owners of Basque ironworks meant that the start of industrialisation was delayed; in the early years, the efforts in Asturias to modernise the exploitation of coal and promote the steel industry were equally unsuccessful. It was not until foreign industry, especially in England, began to require large quantities of iron that the Basque steel industry joined the industrialisation process that was already underway in northern Europe.

The exploitation of the iron ore deposits in Vizcaya and Santander at the end of the 19th century marked the beginning of the industrialisation in the Bay of Biscay. The abundance of hydrological resources due to the proximity of important mountain ranges was the main factor driving industrialisation in northern Spain. Water power was used in Vizcaya for the first paper mills, and construction soon began on infrastructures to harness hydroelectric resources and generate power.

With support from foreign capital –English and French– the first iron and steel industries were built in Santander and Bilbao-Bolueta, soon to be followed by other industries in Asturias, in the towns of Sabero, Mieres and Gijón. The industry was largely extractive as opposed to strictly productive, since a large part of the ore was exported from the ports of Bilbao and Santander before being processed. The creation of the company Altos Hornos de Vizcaya marked the rise of the Basque Country as the country’s first industrialised region since it was tied to the surge in development of the railway and the shipping industry. Another key factor was the birth of major financial entities, such as the Banco de Bilbao and the Banco de Vizcaya, that could finance the large investments demanded by heavy industry.

Aerial image of the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya site, next to the Bilbao estuary, in the town of Barakaldo, circa 1936.

With the electrification of industry, new towns joined in the industrial development –Eibar, Bergara, Arrasate, and Legazpi, among others– and the industrial belt around Donostia was also born, promoting new manufacturing industries related to the steel industry: weapons, locks, tools, etc.

The Spanish Civil War and the subsequent decade forced a temporary break in industrial development that picked up again with the creation of the National Institute of Industry (INI) in 1957. The IN was one of the regime’s main instruments for promoting the country’s economic recovery after the Civil War; its actions were centred on promoting and facilitating the establishment of new industries – and energy was a key element. One notable exception was the electricity sector, which became the essential motor for industrialisation. During this period, plans were drafted to harness the water from a large number of hydrographic basins, mainly in the central Pyrenees, along the Spanish Northern Atlantic coast and in Galicia. In 1958, the INI promoted the creation of the first nuclear power plant in Santa María de Garoña (Burgos).

The Steel Industry in Asturias

Before the Civil War, there were three focal points of the steel industry in Asturias: Mieres, the Moreda-Gijón factory, and the large Duro Felguera factory in Langreo, which were eventually combined into a single company under the name UNINSA. However, the industrial history of Asturias saw a turning point in 1948. That year, the National Aluminium Company (ENDASA) was created, which later became INESPAL and, in the 1990s, was privatised with the sale to ALCOA. The origin of the industry came from the Basque engineer Félix Aranguren, who was in charge of implementing government plans that, in the post-war period, promoted the production of metals such as aluminium as a key factor in the economic recovery. The plan to create a national aluminium company dated back to 1943, and it had been planned for construction in Valladolid to take advantage of the Duero falls. However, technical reasons ended up forcing a move of the plant to Avilés in Asturias.

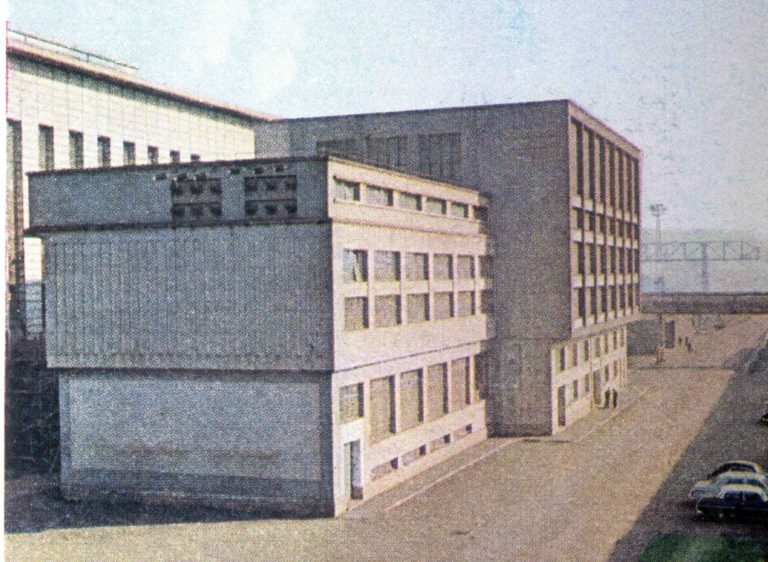

View of one of the buildings of the Felguera Factory (Gran Fábrica de la Sociedad Metalúrgica Duro Folger) in Langreo, built in 1936, and which is still standing today. (https://patrimoniuindustrial.com/).

A few years after the opening of ENDASA in Avilés, the National Institute of Industry (INI) decided to create the national steel company Empresa Nacional Siderúrgica, SA (ENSIDESA) to give a definitive boost to the steel industry in Spain. Because there was an existing iron and steel industry in Avilés –which had led to the improvement of infrastructures– it was chosen that same year as the ideal location for the new company. The geographic suitability of the site did not take into account that the only viable plot in terms of extension and accessibility was marshland subject to flooding by the estuary. Consequently, the building effort was gargantuan, and the poor quality of the land greatly complicated the construction, especially the foundations. The complex’s first blast furnace was not brought online until 1957. From that moment forward, the population of Avilés saw explosive growth, rising from 20,000 to 80,000 inhabitants in just a few years.

In addition to the coking plants and the blast furnaces, ENSIDESA initially promoted the construction of production facilities such as the thermal power plant –demolished in 2007–, the Martin-Siemens steelworks, the LD-I steelworks, the warehouses for pit furnaces and hot rolling machines. and the port facilities in the new docks built by the company. There were also auxiliary buildings of architectural importance, such as the telephone exchange, the fire station, the hospital or the department of transportation. In keeping with its paternalistic project, new towns were proposed for the workers at the same time, notably Llaranes, which was remarkable for its architecture and its exceptional urban development, equipped with all kinds of services, in line with a clear social segregation.

Franco’s Reservoirs

All this industry needed constant, abundant and reliable energy. Although the construction of reservoirs is widely associated with the public works project from the early years of the Franco regime, the truth is that the regime took up pre-existing plans outlined during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, and even from the period of the Second Republic. The severe drought that affected Spain in the 1940s also led to low electricity production, which hampered the potential growth of Spanish industry. This convinced the authorities that the earlier plans needed to be made more ambitious in both scale and number.

The military uprising against the government of the Republic that led to the Spanish Civil War enjoyed majority support in Spanish rural areas. However, a few years after the end of the war, inland Spain began to empty out in an exodus towards large cities like Madrid, Barcelona and Bilbao. General Franco, indebted to the people from rural Spain who supported him, knew that the future of the country would play out in the cities. However, in the early years of the regime, large modernisation programs were started in the interior, which was constantly emptying of its inhabitants.

Among them, two large programs, which were complementary to an extent, covered large expanses of territory and had undeniable social and economic consequences, as well as effects on the landscape. On the one hand, extensive colonisation projects were carried out in the interior through the construction of new rural settlements associated with agricultural development programs. For this to be feasible, a solution had to be found for the historic water shortage in Spain’s interior through the construction of pharaonic hydraulic projects. Water, however, was not only used for agriculture or consumption; it was also essential to producing electricity, which was key to developing industry in the cities – the great hope for pulling the country out of misery. The countryside and the city were facing off over a resource that, in much of Spain, was and always will be scarce. Renowned professionals in architecture and engineering played a central role in the development of these programmes and designed some of the most impressive and high-quality projects in Spain from the mid-20th century.

By the end of the war, Spain has been devastated by battles and drought. In the year hostilities ceased, 1939, the National Institute of Colonisation was created under the Ministry of Agriculture. The enormous task of modernising the Spanish countryside was undertaken through the National Transformation and Colonisation Plan. More than 300 new towns were built, initially housing more than 55,000 families who were granted homes and land as property as long as they complied with the strict moral rules the regime imposed on them. If the aim was to increase agricultural productivity and thus alleviate, in part, the famine that followed the war, it was essential to improve irrigation. To that end, the regime made the construction of dams a priority and, in keeping with their habitual practice, fodder for propaganda.

The devastation in Spain, was compounded by a lack of rain; the drought that spanned the entire decade of the 1940s is one of the most severe in living memory. The estimates that had been made up to that point for the storage of water in reservoirs were clearly insufficient. Out of urgent necessity, water policy became a priority of the regime. But water wasn’t just a necessity in the countryside; it was also necessary for cities, and especially for industry, with an electricity demand that began to rise, slowly, in line with the country’s economy. Because of the drought, water was not just scarce in the countryside, it was also insufficient to generate the electricity demanded by cities and their industry.

Sometimes these two uses were compatible; other times, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Industry bitterly argued over where it was more appropriate to invest in reservoirs, or how much water should be dedicated to one use or the other, each defending their own interests. The company ENHER, dependent on the National Institute of Industry, was in charge of electricity production and was directed by two well-known engineers: Victoriano Muñoz Oms and Eduardo Torroja. Building reservoirs during the Franco regime was an enormous task: a total of 615 were inaugurated from 1939 to 1975.

The Eume dam (1960) with a 108-meter-high wall, designed by Luciano Yordi and located in a recessed section of the Eume River (Galicia). (Creative Commons)

Between 1940 and 1970, Spain multiplied its volume of reservoir water tenfold, implementing a model that forever changed the features of some provinces. Although Galicia is not an industrialised region, it has significant water resources, especially in the province of Ourense. A large number of reservoirs were built in the province in the early years of the dictatorship and, in many cases, little consideration was given to the preservation of the landscape or historical heritage. Entire villages, farmland, important monasteries, and even Roman ruins disappeared under the water.

The Waterfalls of Asturias: Joaquín Vaquero Palacios

The first power plants in Asturias were built by Narciso Vaquero, a public works assistant who undertook a major business development initiative. One of his most important projects was the water supply for the city of Oviedo. Narciso Vaquero’s son, Joaquín Vaquero Palacios, had a clear artistic sensibility from the time he was a child. He chose a career in architecture, as a vocation with some connection to the visual arts, and went to study in Madrid. The first years of his professional activity were focused on painting, When he finished his architecture degree, he settled in Paris and later in New York, where he tried to make a name for himself as an artist and exhibited in various art galleries. With his former classmate, the architect Luís Moya, he participated in the competition for the Columbus Lighthouse monument, finishing third in the second round.

Upon his return from the United States, he continued pursuing his ambition of making a career in the art world, but began combining it with his first architectural projects, built in a marked rationalist style.

Vaquero Palacios was in Oviedo when the Civil War broke out; from there he moved to Galicia with his family, settling for a few years in Santiago de Compostela. He was involved with a number of architectural projects there: he restored important historical buildings in the city and built new ones, such as the wholesale market in Santiago. After the war, he travelled again through Europe and America, and in 1965 he moved to Rome when he was appointed director of the Spanish Academy of Fine Arts.

Aerial image of the Mercado de Abasto de Santiago, a work by Joaquín Vaquero Palacios from 1937 and in neo-Romanesque style (turismo.gal).

Vaquero Palacios’ professional career, which had focused on artistic production, took an unexpected turn when he was commissioned to build a series of hydroelectric power plants in his native Asturias. Hidroeléctricas el Cantábrico, the company that gave him the commission, originated with one of the companies his father founded: the Junta de Saltos de Agua de Somiedo. The projects became an extraordinary example of the integration of the arts and architecture. He collaborated on some of them with his son, also an artist: Joaquín Vaquero Turcios.

Vaquero Palacios, for his part, was the author of the fabulous Salime waterfall, the Proaza power plant, and the decoration of the Miranda power plant, with a 6 x 10 m mural inside and two 11-meter-high figures on the exterior. They are all are unique examples of the confluence of engineering, architecture and art.

The Salime waterfall on the Navía River is a perfect example of the importance that the Franco regime placed on hydraulic projects. This is evident in the extraordinary quality and detail of the project, beyond its engineering function; architects and artists collaborated on the project in an attempt to make it an emblematic, coherent, total work.

The Salime dam and the hydroelectric plant were built between 1946 and 1955. The dam on the Navía River formed the largest reservoir in the Spanish region of Asturias, just 20 kilometres from the Cantabrian Sea. In this case, because the region is humid, with ample water, the supply is used almost exclusively for electricity generation, which was very necessary for one of the most industrialised regions in Spain.

Despite the technical complexity of the work, the aesthetic aspects of the Salime dam were attended to with great care. The architect’s son assisted his father in this task: the exterior concrete bas-reliefs and immense murals in the refined interior rooms – the turbine room is one of the jewels of the plant with a 300 m2 mural – are combined with the expressive concrete forms of s the overlooks or the elements that crown the spillways.

In Proaza, the whole volume of the turbine room is conceived as a colossal exposed concrete sculpture. The plant is considered one of the most emblematic works of 20th-century Spanish industrial heritage that is still in operation today.

Through the end of his life, Vaquero Palacios received multiple awards and recognitions for his artistic activity, which, at least while he was alive, received much more attention than his built work. The work of Vaquero Palacios for the Hidroeléctrica del Cantábrico, for which he also built the headquarters in Oviedo, was displayed in a dedicated exhibition at the ICO Foundation in Madrid called La belleza de lo descomunal [The Beauty of Enormity].

Castilla by Joaquín Vaquero Palacios, 1972, from the collection of the MNCARS, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

Bibliography

HUERTA, Toño, Asturias industrial. Un recorrido por su patrimonio histórico, Delallama Editorial, San Pedro, Asturias, 2021.

GARCÍA BRAÑA, Celestino, GÓMEZ AGUSTÍ, Carlos, LANDROVE, Susana, PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, eds., Arquitectura del movimiento moderno en España. Revisión del Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edificios del Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, / Arquitectura do Movimento Moderno em Espanha, Revisão do Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edifícios do Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Arquia, Barcelona, 2019.

Vaquero Ibáñez, Joaquín (com.), Joaquín Vaquero Palacios. La belleza de lo descomunal. Asturias, 1954-1980 [Catálogo de la exposición homónima], Fundación ICO, Madrid, 2018.

GOZÁLEZ PORTILLA, Manuel, Urrutikoetxea Lizarraga, José, ZARRAGA, SANGRONIZ, Karmele, “Otra industrialización del País Vasco: las pequeñas y medianas ciudades: capital humano e innovación social durante la primera industrialización”, en Historia de la Población 10, Universidad del País Vasco, Servicio de Publicaciones, Bilbao, 2015.

GONZÁLEZ ROMERO, José Fernando, Arquitectura Industrial en Avilés y su Ría, Ediciones Trea, Gijón, 2014.

AA VV,La fábrica, paradigma de la modernidad [actas del VII Congreso DOCOMOMO Ibérico], Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona, 2012. ISBN 978-84-615-7456-8. (FORMATO dvd)

GARCÍA BRAÑA. Celestino, LANDROVE, Susana, TOSTÕES, Ana, eds., La arquitectura de la industria, 1925-1965. Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona, 2004.

GONZÁLEZ ROMERO, José Fernando, MUÑOZ DURARTE, Pelayo, Minería del carbón y Arquitectura Industrial en Asturias, Ediciones Trea, Gijón, 2013.

GONZÁLEZ ROMERO, José Fernando, Arquitectura industrial de Oviedo y su área de influencia. Una realidad dúplice, Ediciones Trea, Gijón, 2012.

APRAIZ SAHAGÚN, Amaia, MARTÍNEZ MATÍA, Ainara, Arquitectura industrial en Gipuzkoa [formato digital, accedido el 23/03/2022], Asociación Vasca de Patrimonio Industrial y Obra Pública, AVPIOP-IOHLEE, 2011.

http://www.artxibogipuzkoa.gipuzkoakultura.net/libros-e-liburuak/bekak-becas06-es.php

GONZÁLEZ ROMERO, Fernando, MUÑOZ DUARTE, Pelayo, Arquitectura Industrial en Gijón. La huella de una ausencia, Editorial Trea, Gijón, 2008.

AA VV,Arquitectura e industria modernas: 1900-1965 [actas II Seminario Docomomo Ibérico], Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona, 2000.

CAPITEL, Antón, “Joaquín Vaquero Palacios: tan arquitecto como pintor”, en Arquitectos 141, Consejo Superior de los Colegios de Arquitectos de España, Madrid, 1996.

DEL CASTILLO, Jaime, RIVAS, Juan A., “La Cornisa Cantábrica: una región industrial en declive”, en Papeles de Economía Española 34, 1988.

“El Arquitecto y pintor Joaquín Vaquero: su historial y obra pictórica”, en Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 12, Ministerio de la Gobernación, Dirección General de Arquitectura, Madrid, 1941.