Miguel Fisac Serna

Daimiel (Ciudad Real), 1913-Madrid, 2006

Born in 1913 in Daimiel (Ciudad Real), Miguel Fisac moved to Badajoz to complete his Baccalaureate at the National Institute. In 1930, he went to Madrid to begin his studies of architecture at the Central University (now UCM), where he passed the complementary course in 1934. He was a classmate of Francisco de Asís Cabrero and José Luis Fernández del Amo, and his teachers included Antonio Flórez Urdapilleta for drawing and César Cort for urban planning. His studies were interrupted due to the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. He avoided being pulled into the conflict by hiding in the attic of his family home in Daimiel from July 1936 to October 1937. From there, he fled to France through the Pyrenees, accompanied by Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer and several other members of the Catholic organization Opus Dei, which he had joined one year prior. After the war was over, in 1939 he returned to his studies at the Madrid School of Architecture and began collaborating in the studios of Ricardo Fernández-Vallespín (1940) and Pedro Muguruza (1941), together with Asís Cabrero and Rafael Aburto. He earned his degree in architecture in 1942 and received a prize for his Final Degree Project from the Royal Academy of San Fernando. In 1955, he left what was then called the Opus Dei Secular Institute, and he married Ana María Badell in 1957. The family settled in a house he designed (the architect’s House and Studio) in 1956 in Cerro del Aire, on the outskirts of Madrid, where he died in 2006.

Of his work, 45 projects are included in the Iberian Docomomo Registry. Many of his early designs, through 1959, were the product of the trust placed in him by his companion during his time in France, José María Albareda – an important member of Opus Dei and a professor of Geology at the University of Madrid, a scientist, researcher, priest and permanent secretary of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) since its creation in 1939. Fisac’s first projects were in Madrid, where he maintained the classicist principles and languages he had learned during his education. This is evident in the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, from 1942, the central building for the CSIC, from 1943, and the Edaphology Building, from 1944. In 1945, he designed the Canfranc Hydroelectric Power Plant together with the engineer Conrado Sancho Rebollida. There, and in the projects that followed, he left behind the classicist modes and language for a functionalist ideal as a principle of modernity. He incorporated organic formalisms with ties to a certain sensibility in modern Scandinavian experiments, which the architect from La Mancha always recognized. In a similar vein, in Madrid, he designed the Goerres Library (1947), the Daza de Valdés Institute of Optics (1948), the headquarters of the Juan de la Cierva Trust, and the CSIC Centre for Biological Research (1949). This last commission was key to the orientation of his subsequent designs. The Cajal Institute awarded him a scholarship for travel, which he undertook together with José Antonio Balcells, visiting the animal experimentation laboratories in central Europe and Scandinavia: France, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Denmark and Sweden. He was able to learn about and form a direct opinion of the new architecture that was being designed outside Spain, which was politically and culturally detached from the rest of the world at the time. The works he saw by Le Corbusier left him disappointed, and it was largely the sensitivity of Erik Gunnar Asplund – with his modernity permeated by an intrahistorical poetics, as seen in the expansion of the Gothenburg Town Hall in Sweden (1934) – that convinced him of the Modern Movement’s error in excluding local factors. He opted for a poeticized formal language that combined organic functionality with a lack of ornamentation, references from which he never strayed.

He also understood the need to travel abroad to see the new modern architecture, making drawings and keeping detailed travel notebooks. We still have access to the materials from his trip to Germany (1951), the Far East (1953), financed by the Dominican Fathers, where he visited the Philippines to oversee the construction of the Manila Cathedral, and continuing to Japan, China, India and Israel, Switzerland and Austria (1954), and around the world (1955). In the United States, he met with Richard Neutra, whom he befriended, and was able to see works by Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. He returned to Holland in 1960; he moved to the United States and then Mexico in 1962, and to Stockholm in 1982.

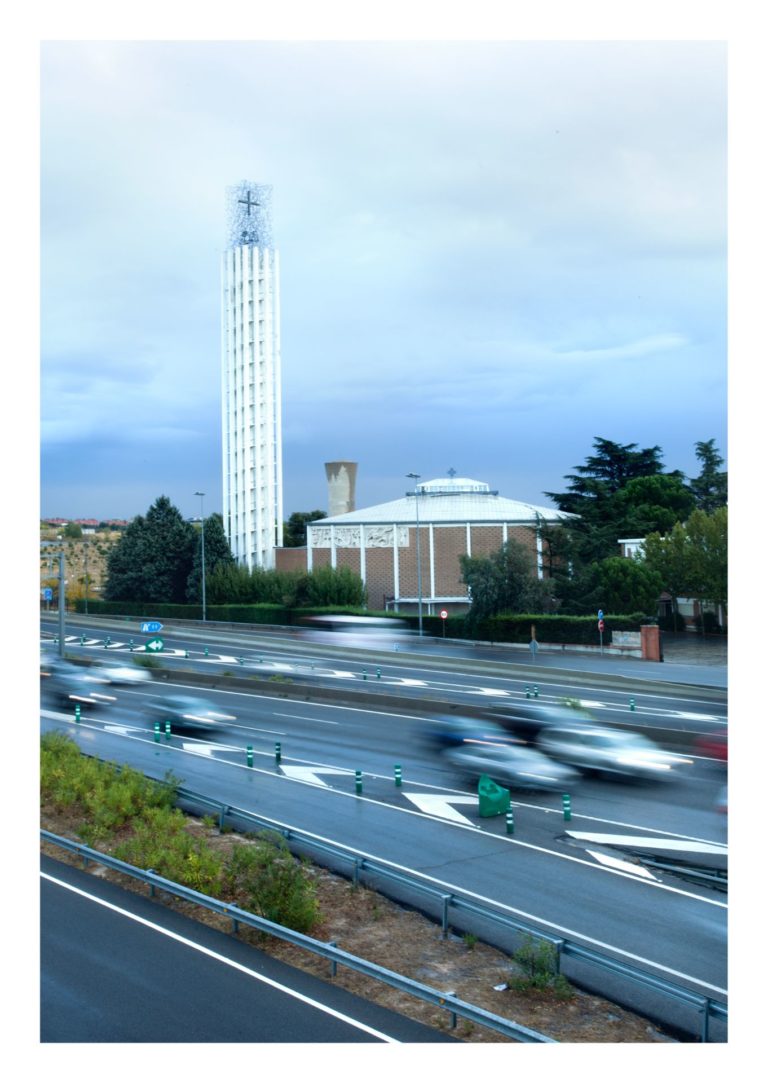

Following those initial Scandinavian influences, what was his ‘first modern work’, as he called it, emerged in 1951: the Daimiel Labour Institute (Ciudad Real) and the Almendralejo and Hellín Labour Institutes (1952, Badajoz and Albacete). The Apostolic College of the Dominican Fathers in Valladolid (1951) was a key project in his career. He received the first international recognition for this design, when the church was awarded the Gold Medal at the Sacred & Hieratic Art Exhibition in Vienna in 1954. It was the first instance of one of the most well-known themes in his work, which continued throughout his career: the search for a new type of religious space in keeping with his idea of architecture, ‘a bit of humanized air’, drawing on the religious sensitivity that he never left behind. In this architecture, light takes on a high symbolic value. Also upon his return from the East (1954), drawing on the influence of Asian cultures, he planned the garden in the cloister-courtyard, which also reflected his admiration for the Alhambra and Scandinavian influences, as well as Eastern traditions. From this moment forward, gardens became a major theme in many of his designs. This design approach characterized the first stage of his career, with buildings such as the Teacher Training Centre in Madrid and the building for the National Research Council (CSIC) in Santiago de Compostela (1952), the Secondary School and Trade School in Malaga (1953), the three single-family homes for Alter in Madrid (1954) and the Market in Daimiel (Ciudad Real, 1955). For the order of the Dominican Fathers, he completed three final projects: the Convent, Seminary, and Church of Saint Peter Martyr in Alcobendas (1955), which show a clear Scandinavian influence (in this case, Arne Jacobsen’s Aarhus City Hall in Denmark); the Cinema-Theatre at the Apostolic College of the Dominican Fathers in Valladolid; and the Pavilions for the students and Dominican nuns in Santo Tomás de Ávila (1959). He also built several other significant projects for the CSIC in Madrid, including the Geological Research Centre (1959). In all these initial projects, he incorporated the design of the furniture, drawing from the Scandinavian idea of integrating interior design with architecture.

In 1957, living in his house in Cerro del Aire, he designed two cultural buildings that rounded out this first stage, strongly influenced by the poetics of Scandinavian architecture: the Casa de la Cultura [House of Culture] in Ciudad Real and the Casa de Cultura in Cuenca, and in 1958 he designed the parish church of Our Lady of the Coronation in Vitoria.

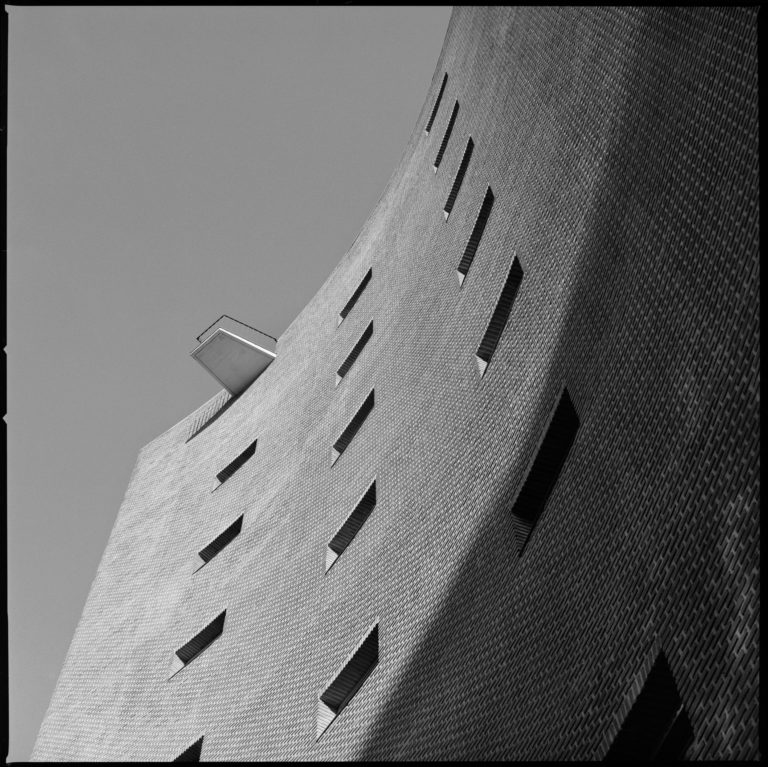

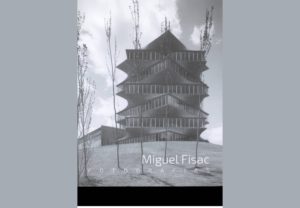

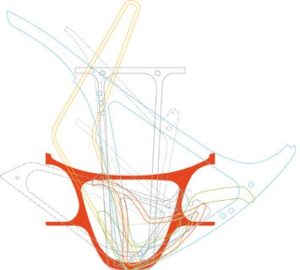

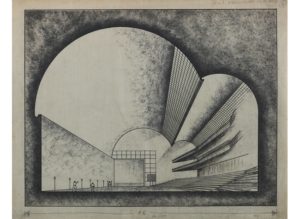

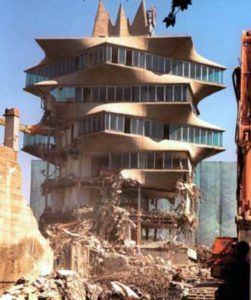

From there, he began building in Madrid, adopting concrete as the material most suited to his architecture. Fisac used to explain that he would think about three aspects when he was designing: ‘why’, ‘how’ and ‘a certain something’. After the ‘why’, in which he resolved the functional needs of the building, the exposed concrete formwork and prefabricated beams would provide the ‘how’ of construction, and, from that harmonious relationship, ‘a certain something’ would emerge in the beauty of the building. In the Farmabión Laboratories, from 1957, the structure and layout of the floor plan are based on reinforced concrete with aluminium and glass façades. The work shows a certain influence of the Mies’s Perlstein Hall (1945), which he had visited and drawn two years before. Fisac began using enclosures and beams made from hollow-core, prefabricated and post-tensioned concrete in the projects for the Centre for Hydrographic Studies in 1959, the Made and Alter Laboratories in 1960, and in the portico and framing for the Los Manitos Apostolic School in Calahorra (La Rioja) in 1961. That same year, he began using systems based on prestressed hollow concrete beams, which he referred to as ‘bones’, for the Núñez de Arce secondary school in Valladolid, patenting the ‘Valladolid beam’. He used this patent in different projects for the CSIC: in 1963, in the Institute of Organic Chemistry, the Juan de la Cierva Information and Documentation Centre, and the IBM Electronic Calculus Centre; and, in 1965, in the Santa María del Mar School in A Coruña, the Santa Ana Parish Church, the Prefabricated Housing, the Asunción School and the Jorba Laboratories, where he built his La Pagoda tower, now demolished.

Throughout the 1960s, Fisac continued with this work on prefabricated concrete structures; he patented numerous ideas for beams and façade elements that he employed in most of his buildings. He used them for the façades of the Moroder Building in Valencia (1961), the house on Camino Alto in Alcobendas (1963), the Vega Building (1964), the IBM Office Building in La Castellana (1966), the House for Alonso Tejada in Somosaguas (1967), the Bioter Building (1969), and the Pavilion at the ITI School in Málaga (1968). He used prestressed beams in the Barrera House in Pozuelo de Alarcón (1963), the New Church of the Holy Cross in Oleiros (1967, A Coruña), and the San Patricio Winery in Jerez de la Frontera. However, he continued using metal structures in buildings where he considered it appropriate, as was the case with the Parish Church in Punta Umbría (1964), the Church of Our Lady of the Pillar in Canfranc (1965), the Parish Centre of Saint Mary Magdalene in Madrid (1966), the Church of Our Lady of Altamira in Madrid (1983), and the Church in Pumarejo de Tera (1984, Zamora).

Experimentation with concrete continued as his obsession until his final projects, although he introduced a new resource: flexible formwork. For Fisac, structures that relied on rigid formwork denied concrete’s soft and viscous “genetic origin”, instead making it appear stonelike. In the 1950s, he patented the first of flexible formwork systems for concrete so that, when it hardened, it would not lose its identity. The first project using flexible formwork for walls in Madrid, the Rehabilitation Centre for MUPAG (1969), was followed by the architect’s own studio in Cerro del Aire (1961) and the Tres Islas Hotel in Fuerteventura (1972), the Social Building for the Sisters Hospitallers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Ciempozuelos (Madrid, 1985), and the offices of the Mediterranean Savings Bank in Alicante (1988). He also used this system for the Fisac Family Home in Almagro (1978), where the couple assembled the formwork and poured the concrete themselves, alongside traditional walls. This ongoing architectural experimentation is evident in his holiday homes. He experimented with vernacular systems in his House in Canfranc (1959, Huesca) and the House on the Costa dels Pins, Son Servera (1962, Mallorca); with modular concrete systems in his House in Mazarrón (1968, Murcia); and with the relationship between the architecture and the native flora in the House in Son Servera, Mallorca (1962). He continued experimenting with flexible formwork through his final designs: the Bioter Factory in Santander and the building for Editorial Dólar in Madrid (1974). Outside the period of the Docomomo study, he did something similar in the tomb for Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in Burgos (1980), the Parish Complex of Our Lady of Altamira in Madrid (1983), the Church in the Torre Guil Development (1991, Murcia), the Municipal Theatre in Castilblanco de los Arroyos (2002, Seville, together with Manuel Flores Llamas), which now bears his name, and the winning competition entry for the Alhóndiga Sports Pavilion in Getafe (2003, Madrid, with F. Sánchez-Mora, S. González, B. Aleixandre, and L. Oro).

The question of housing was essential for Miguel Fisac, although he never received major public commissions. He built more than 130 single-family homes and collective housing projects (to house more than three families). His interest in collective residential architecture began in 1950, when he was awarded the first prize by the COAM for a public housing project, a design for a block based on ‘a string of houses’, which was never built. In 1958, he used this typological solution, in the form of experimental minimal housing, for the Colonia Puerta Bonita, in Madrid, in which he participated alongside 14 other architects. Also in Madrid, together with Enrique Simonet Castro, he built the Office Building and Housing for CIASA (1955), the Pou Building in A Coruña (1964), and the Housing for the Society of Authors (SGAE) in Madrid (1966). Outside the period of the Modern Movement, his most relevant buildings are the Residential Building with Flexible Formwork in Daimiel (1978) and his last project, built together with S. González and F. Sánchez-Mora, the Residential Building in the Ensanche de Vallecas (Madrid). The latter introduced a new, posthumous invention: ‘poured architecture’, using hollow prefabricated formwork that included the building services, for structural façade panels, resulting in ‘architecture without scaffolding or bricklayers’, as he called it.

Despite the apparent continuity in the development of his work, starting in the 1970s Miguel Fisac’s studio saw a significant decrease in commissions, which the architect attributed to his break with Opus Dei in 1955. Fisac was forced to work outside Spain, anonymously, for a developer in the United Kingdom. Under other architects’ names, he completed housing projects for this company on the outskirts of London as well as hotels for the United Arab Emirates in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, where he travelled on several occasions. Additionally, he continued to paint on canvas using a technique of his own invention – latex paints combined with local soils – and he capitalized on his patents for industrial designs such as the ‘Blancanieves’ fluorescent fixture from 1970, patented in 1985. The first public recognition of his work came in 1993 with the German exhibition Miguel Fisac, Architekt in Munich. It was followed by the CSCAE Gold Medal for Architecture in 1994 and tributes and exhibitions, mainly in Madrid and Valladolid.

Biography by Daniel Villalobos

Relevant Awards and Recognitions

- 1942 graduation Award from the Real Academia de San Fernando [Premio Fin de Carrera de la Real Academia de San Fernando]

- 1950 First Prize in the COAM competition for Minimum Habitat Primer [Premio en el concurso del COAM para viviendas mínimas]

- 1954 Gold Metal in the International Exhibition Sacred Art Vienna

- 1993 Exhibition: “Miguel Fisac, Architekc”, Múnich [1995 in Zaragoza, 1997 in Valladolid]

- 1994 Architecture Gold Metal from the CSCAE [Medalla de Oro de la Arquitectura CSCAE]

- 1996 Painting Exhibition, Madrid

- 1997 Exhibition “Miguel Fisac arquitecto”. Palacio de Santa Cruz, UVa, Sala del Renacimiento. Universidad de Valladolid, January 1997

- 1997 Conferences and Homage to Fisac. Paraninfo UVa. Director: Daniel Villalobos. With: Miguel Fisac, Leopoldo Uría, Juan Antonio Cortés, Víctor Pérez Escolano and Daniel Villalobos

- 1997 Exhibition. Arquerías de los Nuevos Ministerios. Madrid. VII Premio Antonio Camuñas de Arquitectura

- 1999 Gold Metal and Homage, Colegio de Arquitectos de Madrid and Círculo de Bellas Artes

- 2003 National Architecture Award [Premio Nacional de Arquitectura]

- 2004 Doctor Honoris Causa, Universidad Europea de Madrid

- 2007 Exhibition “Miguel Fisac. Huesos varios”. Madrid, 2007

- 2007 I Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura Fundación Miguel Fisac “La materia de la arquitectura”. Almagro (Ciudad Real)

- 2008 Exhibition: “La mirada de Fisac”. Museo de la Universidad de Valladolid, 2008

- 2009 II Simposio Miguel Fisac “Cometas y Paraguas: una relectura de nuestras vanguardias”. Campus Universitario de Toledo. Demarcación de Toledo del Colegio de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha

- 2013 Exhibition Fisac-Sota. Fundación ICO, Madrid

Miguel Fisac detailed Chronology

Selección de textos de Miguel Fisac

- FISAC, Miguel, Autobiografía [Containing the autobiographical text from 1970], Caniche, Bilbao, 2023.

- FISAC, Miguel, Carta a mis sobrinos (estudiantes de arquitectura), Fundación Miguel Fisac, Ciudad Real, 2007 and Colegio oficial de Arquitectos de Ciudad Real/Tecnología y Diseño Cabanes SA, Ciudad Real, 2010

- FISAC, Miguel, Reflexiones sobre mi muerte [Autoedición privada, 1999], Nueva Utopía, Madrid, 2000.

- FISAC, Miguel, España 1999 (Imágenes del Futuro), Planeta, Barcelona, 1990.

- FISAC, Miguel, Arquitectura popular manchega, Instituto de Estudios Manchegos, Ciudad Real, 1985 and Colegio de arquitectos de Ciudad Real, Madrid, 2005.

- FISAC, Miguel, Mi ética es mi estética, Museo de Ciudad Real, 1982.

- FISAC, Miguel, La molécula urbana. Una propuesta para la ciudad del futuro, Ediciones y publicaciones españolas S.A (EPESA), Madrid, 1969.

- FISAC, Miguel, La arquitectura popular española y su valor ante el futuro, Ateneo de Madrid, 1952.

Bibliography

- ARQUÉS, Francisco, LAPAYESE, Concha, eds., Miguel Fisac en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ediciones Complutense, Madrid, 2024.

- GARCÍA-MANZANARES VÁZQUEZ DE AGREDOS, David, NAVARRO GALLEGO, Javier, PERIS SANCHEZ, Diego, Miguel Fisac: Vivienda 1943-2006, Fundación Miguel Fisac/Colegio de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 2023.

- GARCIA-MANZANARES VAZQUEZ DE AGREDOS, David, Fisac. Obra completa. Ed. Fundación Miguel Fisac y Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 2023.

- LIEDANA DE ATAZU, Manuel, “La evolución en las iglesias de Miguel Fisac (1955-1967)”, Trabajo fin de Grado – ETS de arquitectura de Madrid, UPM, 2022.

- PERIS SÁNCHEZ, Diego, Miguel Fisac. El espacio religioso 1942-1991, Fundación Miguel Fisac/Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 2022.

- PERIS LÓPEZ, Diego, PERIS SÁNCHEZ, Diego, NAVARRO GALLEGO, Javier, Miguel Fisac: Mobiliario, Fundación Miguel Fisac and Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 2021.

- GARCÍA BRAÑA, Celestino, GÓMEZ AGUSTÍ, Carlos, LANDROVE, Susana, PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, eds., Arquitectura del movimiento moderno en España. Revisión del Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edificios del Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, / Arquitectura do Movimento Moderno em Espanha, Revisão do Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edifícios do Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Arquia, Barcelona, 2019.

- VILLALOBOS, Daniel, Docomomo Valladolid. Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1975. Industria, vivienda y equipamientos, Fundación Municipal de Cultura del Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2019, pp. 166-207 y 338-361.

- ASENSIO-WANDOSELL GARCÍA, Carlos, PUENTE, Moisés, eds., Fisac, De la Sota [exhibition catalogue], Fundación ICO, Madrid, 2014.

- VILLALOBOS, Daniel, PÉREZ BARREIRO, Sara, RINCÓN BORREGO, Iván, Arquitectura, símbolo, modernidad, Cargraf, Valladolid, 2014, pp. 357-396.

- PERIS SÁNCHEZ, Diego, El espacio religioso de Miguel Fisac, Serendipia, Ciudad Real, 2014.

- RUBIO VALARES, Andrés, Miguel Fisac: La delirante historia de La pagoda (documental), with texys from MALDONADO, Luís and RIVERA, David, Arquia, Fundación Caja de Arquitectos. Documental 28, Barcelona, 2013.

- ROJO TEJERINA, Juan Jesús, “Miguel Fisac Serna. arquitecto. vida y obra”, Trabajo fin de Máster de Investigación en Arquitectura, ETS de arquitectura, Universidad de Valladolid, 2012-2013.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos II. Ocio, comercio, transporte y turismo, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2011.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos I. Lugares públicos y nuevos programas, 1925-1965, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2010.

- PEMJEAN MUÑOZ, Emilio, ed., Miguel Fisac La madera en la Iglesia de San Pedro Mártir y en el Colegio de la Asunción, AITIM, Madrid, 2010.

- AA VV, Miguel Fisac: Premio Nacional de Arquitectura 2002, Ministerio de Vivienda, Madrid, 2009.

- CENTELLAS, Miguel, JORDÁ, Carmen, LANDROVE, Susana, eds., La vivienda moderna, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación Caja de Arquitectos/Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico, Barcelona, 2009.

- ARQUES SOLER, Francisco, ed., La materia de la arquitectura/The matter of arquitectura [Texts I Congreso Fundación Miguel Fisac], Fundación Miguel Fisac, Ciudad Real, 2009.

- VILLALOBOS, Daniel, ed., La mirada de Fisac [catálogo de la exposición homónima], ETSA Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2008.

- ASENSIO-WANDOSELL GARCÍA, Carlos, CABAÑAS GALÁN, Nieves, Fisac 4 obras, Fundación Miguel Fisac/Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, 2007.

- GONZÁLEZ BLANCO, Fermín, ed., Miguel Fisac. Huesos varios [exhibition catalogue], Fundación COAM, Madrid, 2007.

- DELGADO ORUSCO, Eduardo:, “Las iglesias de Miguel Fisac. Miguel Fisac´churches”, en Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea. I CIARC, Arquitectura de lo sagrado. Memoria y Proyecto, Ourense, 2007, pp. 130-161.

- DE RODA LAMSFUS, Paloma, Miguel Fisac. Apuntes y viajes [with text by ARQUÉS SOLER, Francisco, “Miguel Fisac. Arquitecto”], Scriptum, Madrid, 2007.

- AGUILÓ, Mª Paz, “Espacios interiores y mobiliario de Miguel Fisac”, in Informes de la construcción 503, July-September 2006, pp. 57-64.

- GARCÍA, F., “El simbolismo en las iglesias de Miguel Fisac”, in Informes de la construcción vol. 58 núm. 503, July-September 2006, pp.19-32.

- RUIZ-VALDEPEÑAS, R., “El simbolismo en las iglesias de Miguel Fisac”, in Informes de la construcción 503, July-September 2006, pp. 19-32.

- AV Monografías 101, May-june 2003.

- CORTÉS, Juan Antonio, Miguel Fisac, el último pionero, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla y León Este, Demarcación de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2001.

- GARCÍA BRAÑA, Celestino, AGRASAR QUIROGA, Fernando, eds., Arquitectura Moderna en Asturias, Galicia, Castilla y León: ortodoxia, márgenes y transgresiones, Colegios Oficiales de Arquitectos de Asturias, Galicia, Castilla and León Este y León, Santiago de Compostela, 1998.

- CÁNOVAS, Andrés, ed., Miguel Fisac, medalla de oro de la arquitectura, 1994, Ministerio de Fomento, Madrid, 1997.

- ARQUÉS SOLER, Francisco, Miguel Fisac, Pronaos, Madrid, 1996.

- AA VV, Miguel Fisac. Arquitecto [exhibition catalogue], Colegio de arquitectos de Zaragoza/COACYLE Demarcación Valladolid, Zaragoza/Valladolid, 1995/1997.

- Documentos de Arquitectura 10 [monography dedicated to Miguel Fisac], Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Andalucía Oriental, Almería, October 1989.

- CORTÉS, Juan Antonio, “Miguel Fisac, arquitecto inventor”, in BAU, Revista de Arquitectura 1, Valladolid, 1989.

- FULLAONDO, Juan Daniel, Fisac, Servicio de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Madrid, 1972.

- “Miguel Fisac 2. Los años de transición”, in Nueva Forma 41, June 1969.

- “Miguel Fisac 1. Los años experimentales”, in Nueva Forma 39, April 1969.

- MORALES, Felipe, Arquitectura religiosa de Miguel Fisac, Librería Europa, Madrid, 1960.

References to the publications, patents and bibliography of Miguel Fisac