Alejandro de la Sota Martínez

Pontevedra, 1913-Madrid, 1916

Alejandro de la Sota was the son of a military engineer and topographer and, therefore, was educated in an atmosphere of privilege and culture. His love for the arts, which he developed during his adolescence, especially drawing comics and, above all, the piano, stayed with him for the rest of his life. He studied architecture in Madrid during the Second Republic and fought on the Francoist side in the Spanish Civil War. After the war, he received his degree in 1941. Despite living in Madrid for the rest of his life, he always maintained ties with his native Galicia, where his father held official positions. In Galicia, his family ties brought him his first clients and commissions.

Sota’s work can be clearly divided into different stages. Although they all demonstrate a firm commitment to a particular way of understanding architecture, they show substantial changes in their character and formal expression. Luís Fernández Galiano defines these three stages as premodern, modern, and transmodern.

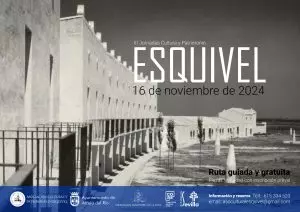

In the early years of his career, Sota worked with the National Institute of Colonization, which he joined in 1941 and where he helped plan rural settlements in newly irrigated areas through 1947. With this ambitious state-sponsored programme, the regime aimed to support rural Spain, in a context of growing scarcity, and mitigate the depopulation caused by the exodus to urban areas. After his departure from the Institute, in the early 1950s Sota received commissions for the construction of entire towns, in which he combined a traditionalist language with the premises of modernity. In the new towns of Gimenells, Esquivel, Valuengo and La Bazana or Fuencarral, as well as in the pavilions for the Feria del Campo [Country Show], Sota abstracted the formal elements of tradition and popular architecture, integrating them into architectural designs and planning proposals with clear ties to modernity. This difficult balance is most evident in his planning projects and in public buildings and churches (such as the cylindrical volume of the church of San Esteban in Cuenca).

Starting in 1955, Sota began to take part in competitions for public buildings, where he tested out more abstract languages and offered an interesting reflection on the representative quality of architecture, which culminated in one of his most important works: the Civil Government of Tarragona (its construction was not completed until 1963). In these designs, Sota abandoned all references to traditional architecture, as well as the organic and lighthearted character of his new towns, to start down a much more refined and diagrammatic path. Increasingly, his buildings were subject to a strict order of grids and structural guidelines. Although, initially, the interiors were enlivened by unique elements like circular staircases, Sota never strayed from the path towards greater abstraction and schematization.

A widespread crisis in 1960 and a lack of work led him to momentarily abandon architecture for a stint as a post office official. Finally, in the mid-1960s, with the improvement of the country’s economic situation he picked up his professional architectural practice and ultimately found success with industrial and sports-related commissions such as the Barajas aeronautical workshops, the Clesa factory, the CENIM research centre, and one of his most significant works, the gymnasium of the Colegio Maravillas in Madrid. All these projects were characterised by the use of metallic structures with long-span trusses and, consequently, by a precise development in section as a synthesis and motor for the design. During this period, he displayed a clear interest in engineering and the rationalization of construction, experimenting, for example, with the prefabrication of prestressed concrete, which he used in the Varela House. Other designs which incorporated the use of this large-scale system in urban fragments following a tapestry format (Mar Menor and Orense), were never built. At this stage, many of his works were designed in collaboration with engineers and industrialists, such as Eusebio Rocas Marcos and Enrique Guzmán.

At the end of the 1960s, several unsuccessful commissions and competition losses, as well as failures in the academic sphere (where he was passed over for a chair in design), led him to begin a more introspective stage and to withdraw from his activity as an architect. He returned to his position with the postal service, which he maintained until his retirement.

His work from this final stage was increasingly abstract, developing his obsession with “the functional box” – understanding buildings as containers where function has a limited capacity to affect architectural form, and the materiality is increasingly bare and ethereal. Many of the designs from this era were never built. However, two of his most important projects for the post office responded to this architectural conception: the computing centre for the Caja Postal in Madrid and the post office headquarters in León.

Increasingly withdrawn from public life, in the 1980s he received multiple awards and tributes for his career and his work.

Biografía a cargo de Roger Subirà

Fotografía de Alejandro de la Sota: Fundación Alejandro de La Sota

Bibliography

- DE LA SOTA, Alejandro, PUENTE, Moisés, eds., Por una arquitectura lógica y otros escritos, Puente Editores, Barcelona, 2020.

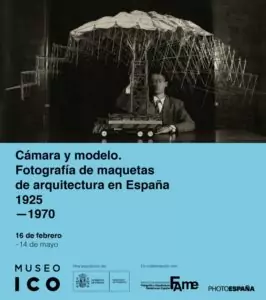

- ASENSIO-WANDOSELL, Carlos, PUENTE, Moisés, eds., Miguel Fisac y Alejandro de la Sota. Miradas en paralelo, Editorial La Fábrica/Fundación ICO, Madrid, 2016.

- ÁBALOS, Iñaki, LLINÀS, Josep, PUENTE, Moisés, Alejandro de la Sota, Arquia/Temas 28, Fundación Arquia, Barcelona, 2009.

- AV Monografías 68 [monographic number, with articles from CURTIS, William, FERNÁNDEZ-GALIANO, Luis, FRAMPTON, Kenneth, NAVARRO BALDEWEG, Juan], Arquitectura Viva, Madrid, 1997.

- THORNE, Marta, “Entrevista a Alejandro de la Sota”, in Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 157, Colegio de Arquitectos de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1983, pp. 106-109.