Viviendas para pescadores Grupo Almirante Cervera

Plaça del Llagut 1-11

08003, Barcelona, España

Viviendas de la Obra Sindical del Hogar

Avenida de los Reyes Católicos 1

49021, Zamora, España

Obra del Hogar Nacional-Sindicalista

Paseo de San Vicente 3, 5, 7, 9, calles Málaga 1, 2, 3, 4, Huelva 1, 3, Jaén 2, 4, 6, Cádiz 6, 8, Bilbao (antes Calle Clarencio Sanz) 1, 3, 5, 9, 11 y paseo de San Isidro 18, 20

, Valladolid, España

Edificio de viviendas dúplex en la Colonia Virgen del Pilar

Calles Mataelpino 1

28002, Madrid, España

Edificio de viviendas para D. José Fernández Rodríguez

Calle Fernando el Católico 47

28015, Madrid, España

Viviendas del Congreso Eucarístico

Plaza del Congrés Eucarístic s/n

08027, Barcelona, España

Poblado de Absorción de Fuencarral B

Delimitado por las calles Isla de Java, Camino Alto del Olivar, la avenida del Llano y la plaza Sasamón

28034, Madrid, España

Poblado Dirigido de Entrevías

Avenida de Entrevías y ronda del Sur, entre FF CC Madrid-Barcelona y FF CC Madrid-Andalucía

28053, Madrid, España

Poblado Dirigido de Fuencarral C

Avenida Cardenal Herrera Oria/calle Manresa/calle Sabadell/calle Mataró/calle Badalona

28034, Madrid, España

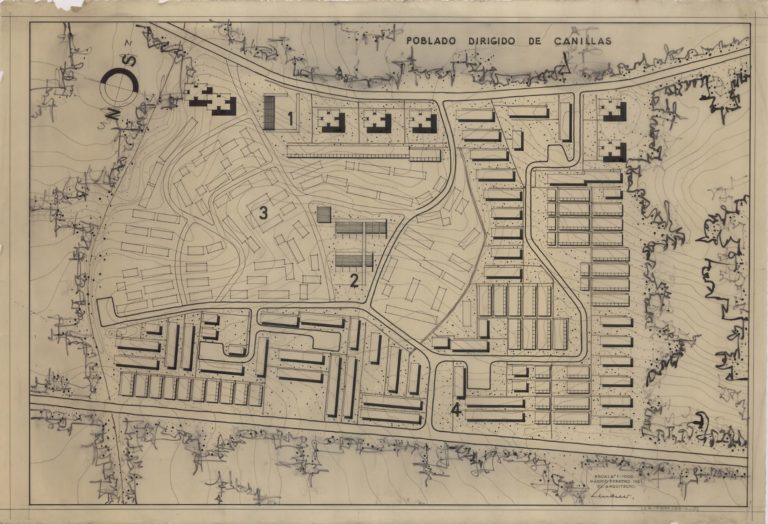

Poblado Dirigido de Canillas

Calle Nápoles/plaza de Nuestra Señora del Tránsito y Gómeznarro, Canillas

28043, Madrid, España

Poblado Dirigido de Caño Roto

Avenida Nuestra Señora de Valvanera/ calles Laguna, Ariza, Escalonilla, Gallur, Vía Carpetana y Glorieta de los Cármenes

28047, Madrid, España

Gran San Blas, fase G

Delimitado por las calles Albaida, Hellín y Alberique

28037, Madrid, España

Poblado Dirigido de los Almendrales

Avenida Córdoba y calles Doctor Tolosa Latour, Hernández Requena, Tomelloso, Santuario, Hijas de Jesús y Santa Cruz de Mudela

28026, Madrid, España

Unidad Vecinal de Absorción de Hortaleza

Calles Acebedo, Albuñol, Abertura, Abarzuza, Ahillones, Albatana, Alcaraz, Aldaya, Alfacar, Abegondo y Alcaudete. Altos de Hortaleza

28033, Madrid, España

- 1937

-

- 1942

-

- 1947

-

- 1949

-

- 1950

-

- 1951

-

- 1952

-

- 1954

-

- 1956

-

-

-

- 1957

-

- 1958

-

-

- 1963

-