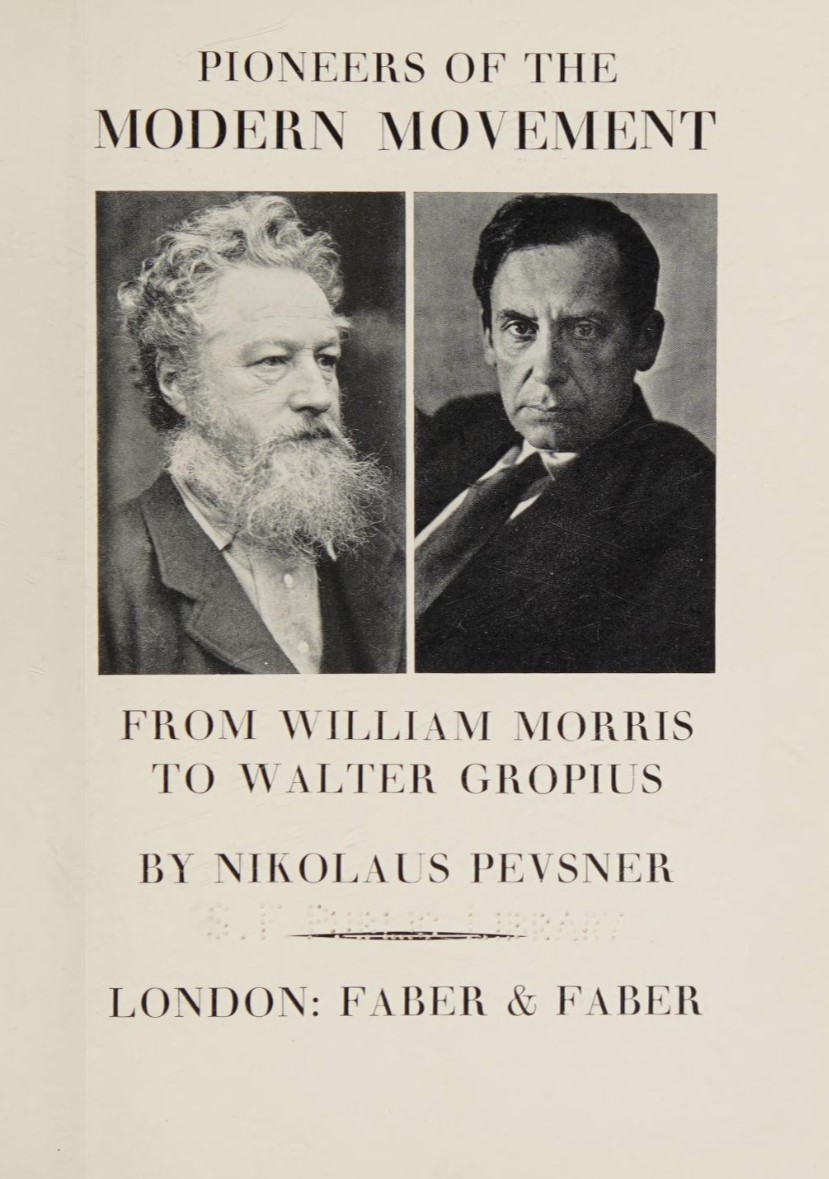

One architectural critic who was especially concerned with explaining the origins of modern architecture was Nikolaus Pevsner. Pevsner was born in Germany, but ultimately became a British citizen. In 1936 ─ preceding Curtis, Frampton and Hitchcock ─ he wrote the text Pioneers of the Modern Movement from William Morris to Walter Gropius.[1] It was the first attempt to trace the lines of thought leading up to modern architecture.

Beginning with the book’s title, he introduces the British variable that Curtis, Hitchcock and Frampton had not taken into account. Pevsner also adds another novelty to his title: he does not call it modern architecture but the Modern Movement. In the following edition, however, revised by the author in 1986, he changed it to Pioneers of Modern Design.[2]

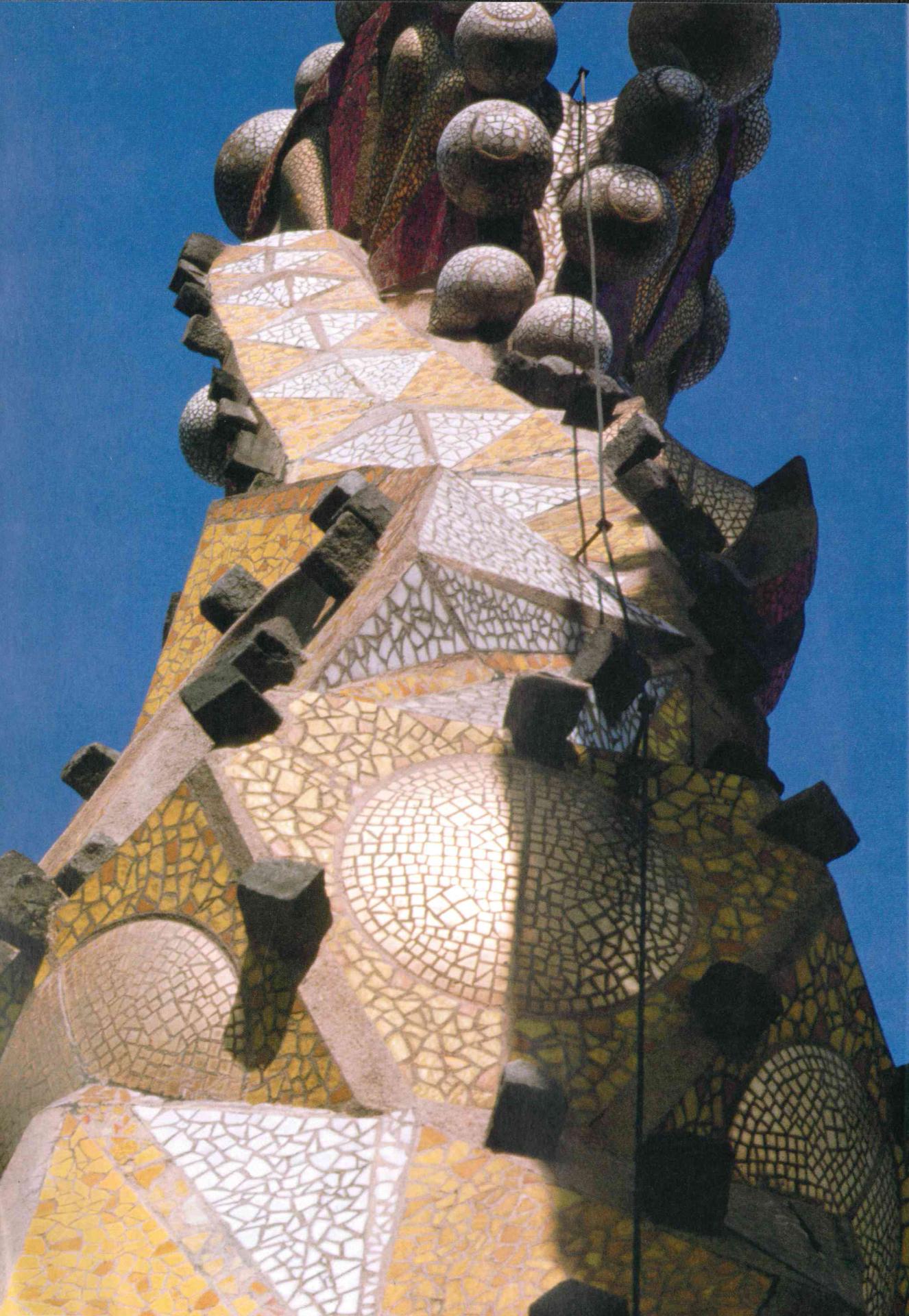

For Pevsner, following the paths that led to the birth of modern architecture involved focusing on the Arts and Crafts movement. And yet, the first image we find in the book is the detail of a pinnacle from Gaudí’s Sagrada Família.

Pevsner’s initial discussion deals with the question of ornamentation, which he sees as the defining element of 19th-century architecture. According to him, industrialization affected the possibilities of using ornamentation in buildings as it had been done previously. The English architect William Morris (1834-1896) ─ the foremost proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement ─ embodied this transition. Pevsner offers two explanations:

- First: a building has to be conceived unitarily in all its aspects. Therefore, it cannot be ornamented indistinctly in just any decorative style.

- Second: craftsmen are being replaced by industrial machinery, and a unique decorative approach for each building can no longer be “invented”.

From his perspective, the fact that Gaudí’s ornamentation was part of the building’s overall design and not an “add-on” made it modern, or at least a precursor to modernity.

Pevsner’s text also focuses on Enlightenment thought as a context that fuelled the shift towards a new architecture. In Pevsner’s view, rationalism, inductive philosophy and experimental science were determining factors in European pursuits during the Age of Reason. He relies on the concept of rationalism to define Enlightenment thought and, although it is not initially applied to architecture, in later chapters rationalism is identified as a necessary condition for modern architecture, ultimately resulting in a new term (architectural rationalism).

The second figure featured in the subtitle of Pevsner’s book is Walter Gropius. All four of the theorist-historians we have cited so far agree that Gropius had a hand in the birth of modern architecture. While Morris opens the book, Gropius brings it to a close. Pevsner makes a convincing argument:

“Walter Gropius studied under Peter Behrens and became the leader of the Bauhaus, one of the important design schools to follow on from the Arts and Crafts Movement”.[3]

In that sense, Gropius is to the Bauhaus what Morris was to the Arts and Crafts movement.

What role did the Bauhaus play in the birth of modern architecture?

[1] PEVSNER, Nikolaus, Pioneers of the Modern Movement. From William Morris to Walter Gropius, Faber & Faber, London, 1936.

[2] PEVSNER, Nikolaus, Pioneers of Modern Design. From William Morris to Walter Gropius, New York Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1949.

[3] PEVSNER, Nikolaus, Pioneers of modern design. From William Morris to Walter Gropius, revised and expanded [1936, con el título Pioneers of the Modern Movement], Yale University Press, New Haven, London, 2005, p 168.