Kenneth Frampton also opens his Modern Architecture: A Critical History by looking into the origins. Although he begins by asserting that “the more rigorously one searches for the origin of modernity, however, the further back it seems to lie”.[1] no more than two sentences later he gives us a date and a reason: it was born at “that moment in the mid 18th century when a new view of historybroought architects to question the Classical canons of Vitruvius and to document the remains of the antique world in order to establish a more objective base on which to work”.[2]

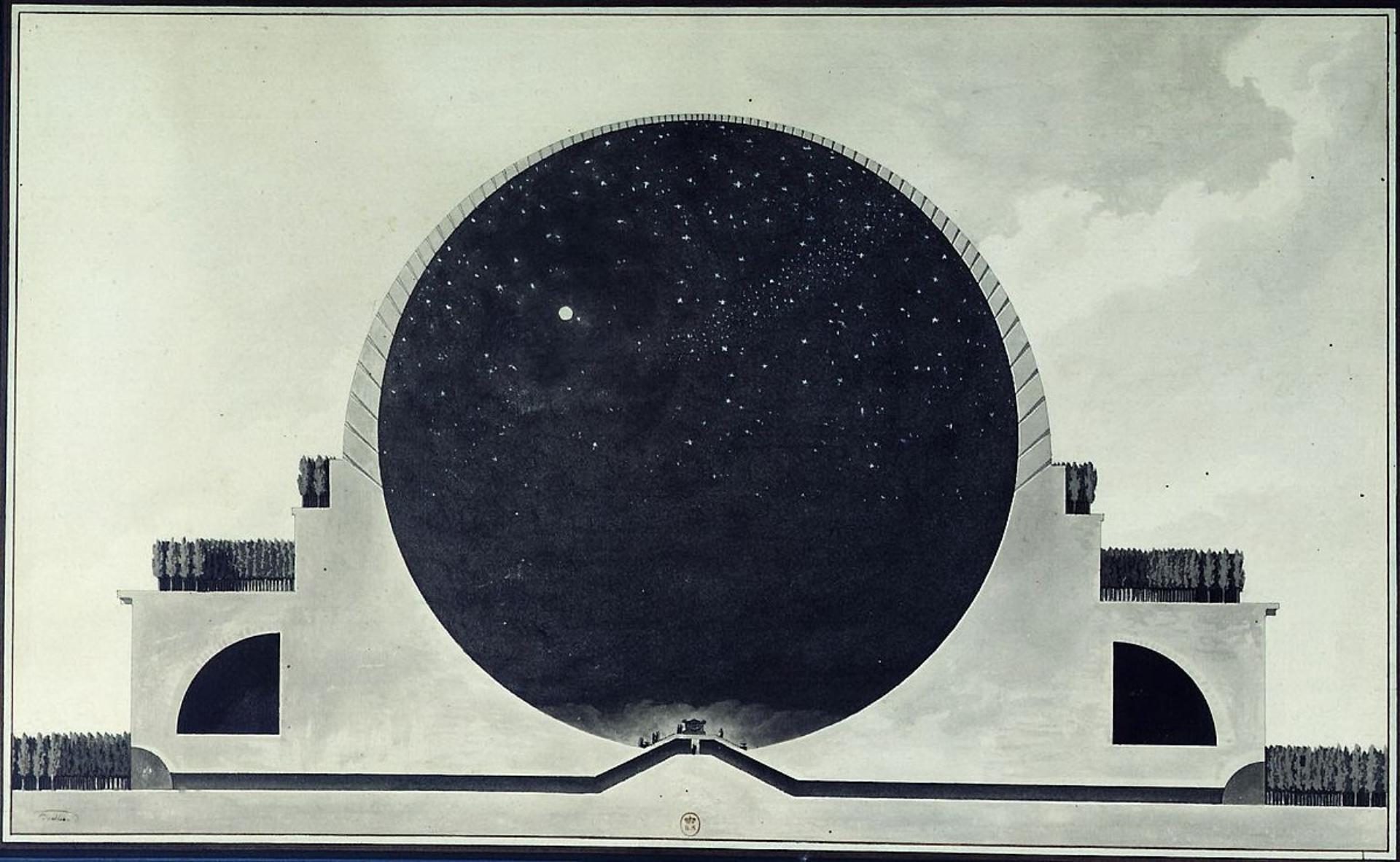

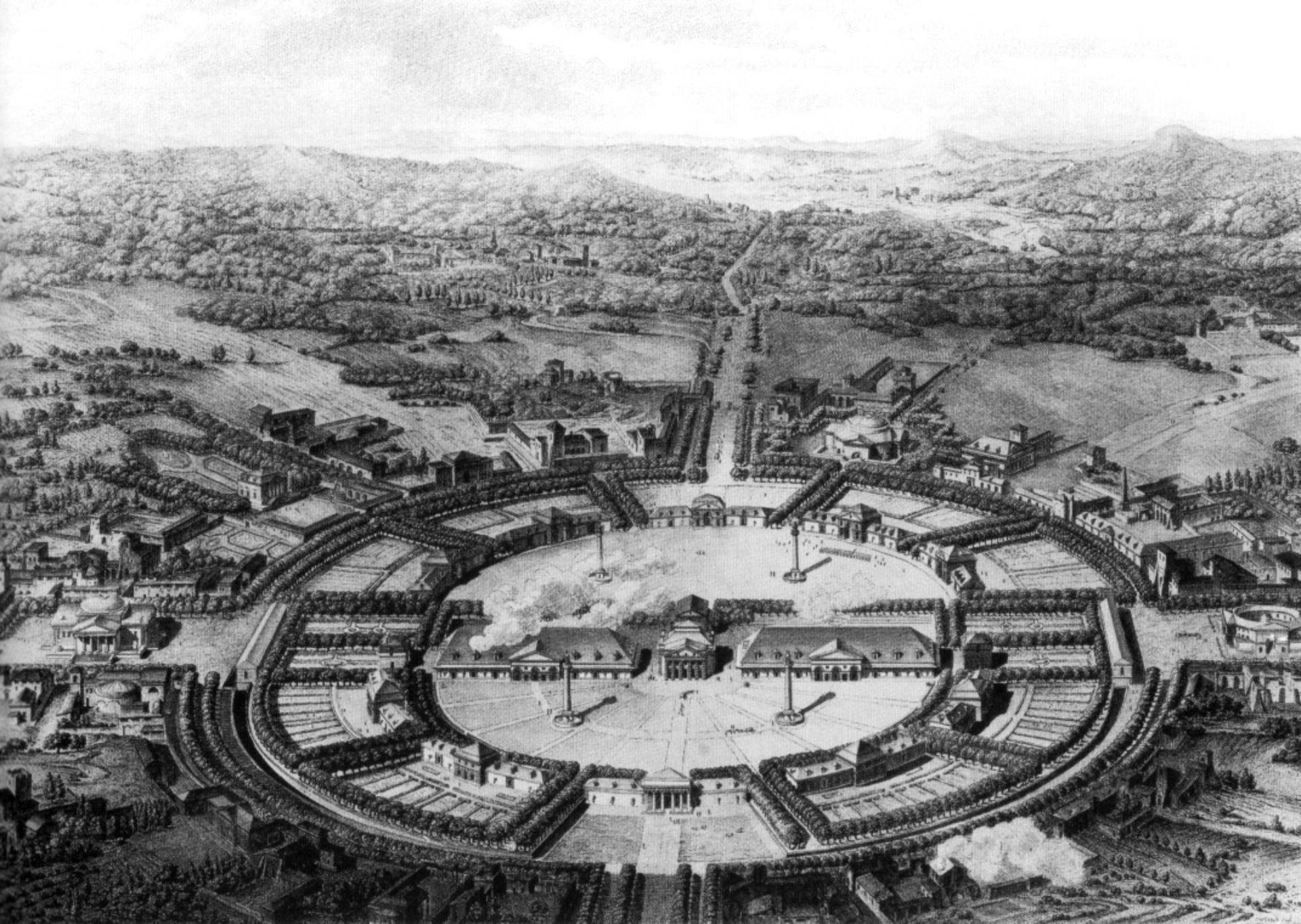

The first images in the book are of Soufflot’s Pantheon in Paris, Boullé’s Cenotaph for Newton, Durand’s treatise, Ledoux’s Ideal City of Chaux, and Schinckel’s Altes Museum. There can be no doubt that, for Frampton, the beginning of modern architecture fell somewhere between 1800 and 1850, and in geographic terms, between France and present-day Germany. According to Frampton, the earliest modern architecture uses the unequivocal language of classicism, with “Vitruvian orthodoxy” and “geometrical purity” [3], but it cannot be understood without considering a number of civil engineering projects associated with new construction technologies.

But is modern architecture compatible with the classical language? For Frampton, it is. He justifies this statement with a very clear and compelling argument: it is during the Enlightenment when we find the enormous changes that will make modern architecture possible, and Enlightenment architecture is neoclassical. While this architecture is not completely modern, he sees in it the tendencies that will become the defining traits of modern architecture: a schematization and progressive erasure of decorative elements and architectural language, which means that the volumes are expressed in an increasingly forthright or “pure” way and there is a progressive rationalization in plan through the adoption of regular, orthogonal layouts or grids.

[1] “Introduction”, in FRAMPTON, Kenneth, Modern Architecture. A critical History, Thames and Hudson, London, 1980, p. 8.

[2] Ibíd.

[3] “Chapter 1. Cultural Transformations: Neoclassical Architecture, 1750-1900”, in FRAMPTON, Kenneth, Modern Architecture. A critical History [1980], Thames and Hudson, London, 2020, p. 16.