The National Institute of Colonization was created by decree on 18 October 1939, published in the Official State Gazette on 27 October. It took the place of the Agrarian Reform Institute (Instituto de Reforma Agraria, IRA), an organization created by the Republic in 1932 for the purpose of improving the economic and social situation of Spanish agriculture.

The issues of the distribution of land ownership, housing for farmers, and inadequate irrigation had been analysed by the Regenerationist Joaquín Costa in the late 19th century, and, for years, various initiatives had sought an adequate solution. In 1932, the Irrigation Works Law (Ley de Obras de Puesta en Riego) and the Agrarian Reform Law (Ley de Bases de la Reforma Agraria) were passed, which failed to satisfy either large landowners or farmers and had important political and social consequences.

The Irrigation Service was created to implement the Law on Irrigation Works; the service drafted the plans for the lower valley of the Guadalquivir and Guadalmellato Rivers and organized a competition for the construction of a series of new towns that would support the colonization and cultivation of the territory. The brief and results of this competition, published in 1934 in issue number 10 of the journal Arquitectura, edited by the Architects’ Association of Madrid, included an important analysis of the problem and selection of diverse and varied solutions, many of which were eventually implemented by the National Institute of Colonization.

Between its creation in 1939 and its absorption in 1971 by the Institute of Agrarian Reform and Development (Instituto de Reforma y Desarrollo Agrario, IRYDA), the National Institute of Colonization built some 300 towns spread across the territory. For those purposes, it was organized into various regional delegations linked to the different river basins, with provincial delegations: Ebro (Lleida, Zaragoza and Tortosa), Duero (Valladolid and Salamanca), Tagus (Madrid, Talavera and Cáceres), Guadiana (Ciudad Real and Badajoz) and Guadalquivir (Jaén, Granada, Córdoba, Seville and Jerez). Additionally, delegations were created for the North (La Coruña), South (Almería and Málaga) and East (València, Alacant and Murcia). Seventy percent of the towns that were built are concentrated between Andalusia (about 110), Extremadura (around 60), and along the Ebro River in Navarra, Aragon and Catalonia (around 40); the rest are distributed throughout the other geographical areas in 27 provinces. The first intervention was the expansion of Láchar (Granada, Tamés, 1943), and the construction of the first new town, El Torno (Cádiz, D’Ors and Subirana, 1944).

The structure of the INC included a large staff of officials who handled all the technical and administrative issues. The architect José Tamés Alarcón directed the Architecture Service from Madrid between 1941 and his retirement in 1975. Under his supervision, some 80 architects carried out projects for the INC, approximately 30 of whom were civil servants employed by the central office in Madrid (Jesús Ayuso Tejerizo, Pedro Castañeda Cagigas, Agustín Delgado de Robles, José Luis Fernández del Amo, Manuel Jiménez Varea and Manuel Rosado Gonzalo) and the various provincial delegations. The other architects were independent contractors and were awarded the commissions directly (Alejandro de la Sota, José Antonio Corrales, Juan Piqueras Menéndez, Carlos Arniches, Antonio Fernández Alba, etc.).

To ensure smooth operations within the INC, a series of internal handbooks were necessary, covering a wide range of technical, labour and administrative issues. More than 500 were written between February 1940 and December 1971. This timespan reflects the evolution of needs and how the Institute dealt with the problems that arose over time. In addition, the organic structure of the INC required intense correspondence between the Central Offices and the various delegations, and there was frequent communication during the development, supervision and control of the design and construction processes.

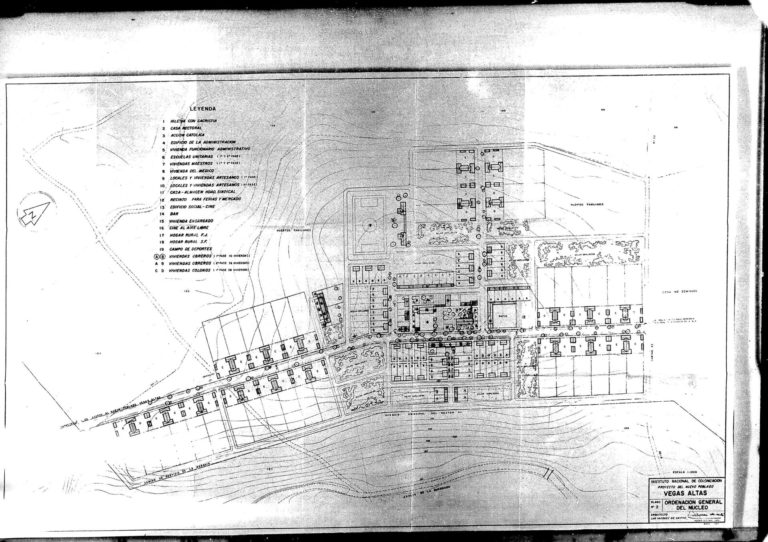

Territorial Implementation and Urban Planning

The development of the INC’s colonization policy was supported by a series of progressive planning instruments: Feasibility Studies, the Declaration of Areas of National Interest, the General Colonization Plan, the Coordinated Construction Plan, and the Land Division Plan. These were all steps that took place prior to the design of the towns themselves.

The placement of the settlements in the territory was inextricably linked to the availability of land that had been declared surplus – i.e., it could be expropriated – since the Law on the Colonization of Large Areas (Ley de Bases de Colonización de Grandes Zonas), enacted on 26 December 1939, aimed to stimulate private initiative for the transformation of areas of high national interest. In addition, handbook number 255, dated June 1950 and titled “Standards for the study and drafting of projects for the general colonization plans for irrigable areas in keeping with the provisions of the law passed on 21 April 1959” established the so-called “wagon module”, which limited the distance between farmland and settlers’ homes to minimize the time spent traveling by wagon. This module was estimated at 2.5 km, so it is common to see a distance between towns of about 5 km, when permitted by the property structure and the availability of surplus land. The property structure also conditioned the establishment of the new towns’ inhabitants, who might be colonists proper – granted their own plots for cultivation – or agricultural workers, who worked on an owner’s lands and would have a small kitchen garden.

There were two contrasting options in terms of where the settlers’ housing was situated in relation to the farms: either scattered near the different fields to minimize travel or grouped into towns. The option of scattered housing implied a higher infrastructure cost and interfered with relations between the settlers, which was a priority for the regime. As such, it was only implemented in exceptional situations. The relationship between the new towns and the existing communication routes was also decisive: the towns could be tangential, located at a crossroads, or at terminal points.

In any case, the design of entire new towns was a challenge for the architects of the INC. The organization of a complex program of housing, agricultural buildings, roads, facilities and public spaces also entailed the creation of a new society, a social framework, and a setting for the inhabitants’ daily lives. And although the architects enjoyed great freedom in their designs, the Institute developed a series of guidelines and formal criteria, both through the aforementioned handbooks and through supervision reports, which stipulated:

- Breaking perspectives, avoiding an excessively rectilinear layout, designing backdrops and public spaces.

- Dividing circulation by type, making vehicle and pedestrian traffic independent, and separating the accesses to the agricultural constructions from the housing.

- Avoiding monotony, using unique elements, variations and public buildings to break up the rhythm.

- Attention to detail, which despite the economic limitations, contributes to a personalization and humanization of the spaces.

The layout of the towns is based largely on orthogonal, curvilinear or mixed networks of streets. They overlap in different ways to achieve the aforementioned objectives. Thus, towns with a completely orthogonal layout and continuous streets are very unusual. This situation does occur in Llanos del Sotillo, however, designed in Andújar (Jaén) by José Antonio Corrales in 1956, where the pedestrian streets lead towards the civic centre built in the central part of the town.

Because public spaces are places for relating and socializing and serve a representative function, the main buildings in the towns are connected to them, in particular to the main square. The first squares were designed following traditional criteria, rectangles closed off with porticoes on several sides, and with public buildings around the edges ─ a town hall, a church, artisans’ workshops. Sometimes a square may limit a main road or passage and the buildings form an L, as is the case of El Solanillo in Roquetas de Mar (Almería), designed by Francisco Langle Granados in 1968.

A common resource in designing public spaces, especially small-scale secondary spaces in new towns, was the plaza turbina [rotor square]: a space formed by leaving a void at the intersection of two perpendicular streets, which are pulled out of alignment, generating a new wealth of perspectives with very few resources.

The scarcity of resources did not prevent the architects from taking great care and paying close attention to detail: the use of simple materials in pavements, including soft paving materials in some cases, the use of stone curbs, and the design of fountains, street lighting, and drinking troughs are some of the examples of the efforts put into the designs.

The Functional Programme: Public Buildings and Housing

The objective of the INC was to ensure settlers would have access to adequate services and enjoy quality of life in all aspects: economic, religious, educational, social, healthcare, etc. Two handbooks are essential to understanding the program of the new towns. On the one hand, number 222, from 1947, titled “Instructions for drafting the designs of new towns”, lists a series of studies to be carried out, including, among other topics, the determination of the number of homes for professionals, doctors and teachers, the number and quality of homes for merchants, artisans and industrialists, and the program of public buildings: a town hall or district office, housing for the bailiff or government secretary, schools, a church or chapel, laundry, a slaughterhouse, barracks for the military police, recreational halls, a cemetery, sports fields, etc. On the other hand, number 246, dating from 1949 and called “Standards to define the construction plan for the new towns built by the National Institute of Colonization”, classified the new towns based on their size and possible evolution, and the functional programme was adapted to that classification taking into account the number of inhabitants expected in the short term and in the more distant future.

The basic program contemplated the construction of a church ─ a chapel-school, since the teachers also used the space for their lessons, an administrative building ─ with a public information service, a mayor’s office, an assembly hall, courtroom, post office, housing for government employees and a medical clinic, artisans’ workshops and shops. As the size of the towns grew, the plans incorporated separate schools for boys and girls, with housing for teachers, a civic centre ─ to serve as a dance hall and cinema, a trade union warehouse ─ centralizing the grain silos, warehouses and sheds for agricultural machinery, and the offices of the Frente de Juventudes [Youth Front] and the Women’s Section ─ generally independent buildings, with a game room, meeting room, a library and an office. Some of the towns also had a cemetery, although these often remained empty.

The ultimate purpose of these towns, however, was to provide decent housing for the inhabitants: in the 300-some towns developed by the INC, almost 30,000 homes were built. And although the fundamental goal of colonization was for the settlers to be the owners of the land they worked, some of the new inhabitants were not landowners but would work on other people’s farms, as agricultural workers. The fundamental difference between settlers’ housing and housing for these agricultural workers was that the latter did not have auxiliary buildings for storing tools or keeping animals. The lots for workers’ housing were significantly smaller. Some unique cases have been seen of towns in the province of Jaén in which all the housing was for agricultural workers, although later reforms incorporated small agricultural buildings.

In both cases, the housing programme was very similar: most of the dwellings had three bedrooms, although some were designed with two, four, and exceptionally, five. They all had a small living-dining room, often a walk-through space including a kitchen and built-in fireplace, and they did not have their own bathroom. In the late 1950s and 60s these programs evolved, and the first foyers, independent kitchens and private bathrooms began to appear. The new towns were an interesting field for experimentation among architects, and the issue of minimal housing was no exception.

Churches and Art

If there is one building in the program of the new towns that allowed architects to engage in greater formal exploration, because of its representative nature, it was undoubtedly the church, since religious celebrations played a significant role in town social life. Although the floor plans frequently take the form of a basilica, one can see an evolution over time toward experimentation with novel triangular or circular layouts. The celebration of the Second Vatican Council promoted a closer relationship with the congregation with the separation of the altar, and placed special emphasis on how mass and the liturgy were conducted, which resulted in a gradual transformation of religious spaces.

The representative character of the churches was highlighted by the bell tower or belfry, the tallest element in these towns, and their presence and verticality served as a landmark in the surrounding landscape.

The Second Vatican Council also promoted the renewal of religious art, but there can be no doubt that the work of José Luis Fernández del Amo, an employee of the Architecture Service at the National Institute of Colonization and director of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, appointed by Joaquín Ruíz-Giménez in 1952, played a central role in the incorporation of abstract works of art in the churches of the new towns: some 70 artists, including José Luis Sánchez and Pablo Serrano (sculpture), Antonio Hernández Carpe and Antonio Suárez (painting), Arcadio Blasco (pottery), and Ángel Atienza (stained glass) contributed artwork for the churches, often without knowing their final destination.

The work of the National Colonization Institute constituted the largest intervention of its kind in 20th-century Europe, entailing a complete territorial transformation that included a series of hydraulic, communication, energy, and housing infrastructures. In terms of architecture, the work of Tamés as director of the Architecture Service allowed broad design freedom for the architects and an acceptance of the values of popular architecture, as it moved in synch with the principles of the modern movement and incorporated a valuable experimental mixture.

Bibliography

- DELGADO ORUSCO, Eduardo, El agua educada. Imágenes del Archivo Fotográfico del INC. 1939-1973, Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente (MAGRAMA), 7 DVD Madrid, 2015.

- DELGADO ORUSCO, Eduardo, Imagen y memoria. Fondos del archivo fotográfico del Instituto Nacional de Colonización 1939-1973. Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, Madrid, 2013.

- CENTELLAS SOLER, Miguel, Los pueblos de colonización de Fernández del Amo. Arte, arquitectura y urbanismo, Colección Arquia/tesis nº 31, Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2010.

- PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, CALZADA PÉREZ, Manuel, scientific coord., Pueblos de colonización durante el franquismo: la arquitectura en la modernización del territorio rural, Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura, Sevilla, 2008.

- CALZADA PÉREZ, Manuel, Itinerarios de Arquitectura nº 5. Pueblos de colonización III: Ebro, Duero, Norte y Levante, Fundación Arquitectura Contemporánea, Córdoba, 2008.

- CALZADA PÉREZ, Manuel, Itinerarios de Arquitectura nº 4. Pueblos de colonización II: Guadiana y Tajo, Fundación Arquitectura Contemporánea, Córdoba, 2008.

- CALZADA PÉREZ, Manuel, Itinerarios de Arquitectura nº 3. Pueblos de colonización I: Guadalquivir y cuenca surFundación Arquitectura Contemporánea, Córdoba, 2006.

- VILLANUEVA PAREDES, Alfredo, LEAL MALDONADO, Jesús, La planificación del regadío en los pueblos de colonización. Historia y evolución de la colonización agraria en España. Volumen III, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo e Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública, Madrid, 1990.

- TAMÉS ALARCÓN, José, “Proceso urbanístico de nuestra colonización interior”, in Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 83, 1948, págs. 413-424.

- TAMÉS ALARCÓN, José, “Actuaciones del Instituto Nacional de Colonización 1939-1970”, Urbanismo COAM, 3, 1948, págs. 4-12