Tourism before the Spanish Civil War

The name Costa Brava refers to the coast of the province of Girona that stretches from the small rock formation called Sa Palomera, in Blanes to the Cap de Creus – between the towns of Cadaqués and Port de la Selva– although its extension is often considered to reach the French border in Portbou. The most emblematic image of this coast is its cliffs and rugged orography, but the Costa Brava also includes long sandy beaches along the Empordà plain and the Bay of Roses.

Although the Costa Brava didn’t enter the collective imagination until after the tourist boom of the 1960s, the name appeared for the first time in the magazine La Veu de Catalunya in 1908. Recent investigations such as the one carried out by the Roses City Council and the Institut d’Estudis Fotogràfics de Catalunya – following the donation of a private collection of photographs – have shown that beach tourism was already a widespread reality in the 1920s and 1930. In fact, there is evidence of this type of tourism in the form of villas, mostly in urban areas, in towns like Sant Feliu de Guíxols, Calella de Palafrugell and Begur, although its impact on the small fishing villages and its environmental effects at the time were limited.

Old picture of the first establishment of the Gavina de S’Agaró hostel, by the architect Josep Massó for the businessman Josep Ensesa. It opened its doors in 1932 with eleven rooms.

One of the first architecturally relevant tourist complexes was the development of the stretch of coast around S’Agaró and Sa Conca beach in Palamós, carried out by the architect Rafael Massó. The construction, which offered high quality in terms of the landscape and scenery, followed the garden city model, with an aesthetic characteristic of noucentisme. In the section closest to S’Agaró, the first luxury hotel complex was built; the La Gavina hotel – which is still in operation – opened its doors in 1932. At that time, tourism was beginning to attract the attention of the public administration, and in 1926 it was further promoted through the creation of the network of Paradores de Turismo [Scenic Hotels] – initially the Junta de Paradores y Hosterías del Reino, and its development continued to grow after the Spanish Civil War. Other initiatives fostered spa tourism, like at Vichy Catalán in Caldes de Malavella, or sea bathing areas associated with health wellness. The limited development of infrastructures delayed initiatives on the Costa Brava and its first and only Parador Hotel didn’t open its doors until 1966. It is an eminently modern building, built by Raimon Duran Reynals on one of the most spectacular spots on coast of Begur. Before the war, the GATPAC also developed proposals for sites intended for working-class holidays and leisure, which went hand in hand with important advances in labour rights. Examples include the Ciutat de Repòs i de Vacances [City of Rest and Holidays] in Castelldefels, a proposal that rounded out the design for the new Barcelona promoted by the Generalitat under the Second Republic, which was never carried out.

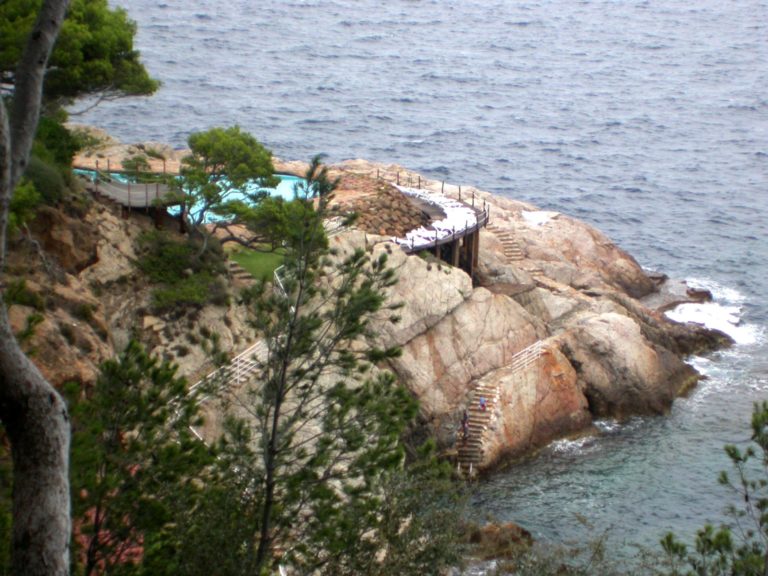

Current image of the Parador de Aiguablava in Begur, built by the architect Raimon Duran Reynals in 1966.

Mass Tourism and the Creation of an Imaginary

The geography of the Costa Brava and the difficult access via train hindered the establishment of large tourist complexes in the early 20th century, which delayed the area’s popularity.

After the Spanish Civil War and the initial autarchic period, the Stabilization Plan of 1959 paved the way for the development and reopening of the Spanish economy. At the time, attracting tourists became a priority for the administration. It was also the beginning of mass tourism: on the one hand, workers’ rights to paid holidays and weekly rest were fully accepted by the business community and the authorities; additionally, workers began having access to private transportation. On the other hand, the development of civil aeronautics made it possible for workers from richer countries to seek out the mild Mediterranean climate for their holidays. Spain offered everything they needed: a cheap country that was largely a blank slate, an unbeatable climate, and one of the longest coastlines in Europe, with spectacular landscapes yet to be discovered. Additionally, there was the fascination and curiosity elicited by the uniqueness of its political regime and a powerful cultural and folkloric imaginary, which exerted a pull on richer countries. Beginning in the 1950s, mass tourism emerged as a genuinely Spanish phenomenon, becoming one of the pillars of the country’s economy. The result was that seasonal tourist movements came to constitute the largest migrations in history: in 1954, 116,453 people arrived in Spain by plane; in 1963 it had grown to 1,061,724, and it had risen to 8,361,468 just 10 years later. Over 20 years, the figures increased 80 fold. This demanded a large-scale development of infrastructure and services.

Ava Gardner during the filming of the Hollywood movie Pandora and the Flying Dutchman in 1950.

Mass tourism on the Costa Brava began at several points simultaneously. One of the first large operations was developed by the architect and businessman Josep Maria Bosch i Aymerich, who joined forces with a family of hoteliers from Barcelona to build a large tourist complex in Begur. It was the Cap Sa Sal hotel, which he designed, and which has one of the best examples of modern gardens in Catalonia, the work of Nicolau María Rubió i Tudurí.

Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich showing the model of the hotel Cap Sa Sal in Begur. The construction began in 1955. Arxiu històric COAC.

Culture and cinema played a fundamental role in making the Girona coastline famous worldwide. Truman Capote finished writing In Cold Blood at a house in the port of Palamós, which was just a small fishing port at the time, the home of an English couple he was friends with. But the real turning point in the tourist development of the Costa Brava was the filming of the Hollywood movie Pandora and the Flying Dutchman in 1950. It brought the most popular movie star of the day, Ava Gardner, to Tossa de Mar. Her glamourous love affairs attracted photojournalists who portrayed the spectacular local landscapes as the backdrop for the glitzy evenings the actress spent with her famous companions, including Ernest Hemingway, one of the main figures responsible for disseminating the images of Francoist Spain across English-speaking countries.

In Palafrugell, the writer Josep Pla used his writing to publicize the landscapes and gastronomy of the Costa Brava. But without a doubt, one of the main reasons this remote coast of north-eastern Spain became known worldwide was Salvador Dalí.

Salvador Dalí (left) and Federico García Lorca (right) in Cadaqués, Girona, summer of 1927. Colection Fundación Federico García Lorca.

Cadaqués

Cadaqués is a town characterised by its geographical location on the Cap de Creus, with very difficult access and spectacular rocky landscapes. Before the Spanish Civil War, Cadaqués was earning fame because of Salvador Dalí, who used its landscapes, especially Port Lligat, as the setting and backdrop for many of his paintings. Artists like Luís Buñuel and Federico García Lorca gathered there.

View of Cadaqués before the tourist boom of the 1960s. 1957 picture from the Archivo Fotográfico de la Dirección General de Turismo

Beginning in the 1950s, marked by Dalí’s imaginary, Cadaqués became an important cultural centre where figures from the artistic avant-garde came together, including Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Mary Fugazzola, among others. Some of the architects who joined this select group, in particular Lanfranco Bombelli and Peter Harnden, attracted by the well-preserved, picturesque town centre, began to design a new kind of architecture which, although modern, showed absolute respect for the local vernacular architecture. Among the Catalan architects, Federico Correa and Alfonso Milà were the first to build in Cadaqués, with a head-on opposition to the “poorly named modern house” which they called a “Cadaqués-style house”. The Casa Villavecchia was their first important work, which ushered in a golden age of modern Catalan architecture concentrated in this enclave on the Costa Brava. It was an old three-storey house with views of the sea, to which Correa and Milà added another half-storey to create a porch and a terrace that appears as a large opening in the façade. The famous Casa Senillosa by Josep Antoni Coderch and Manuel Valls drew inspiration from this early modern house. Magnificent examples of modern urban and suburban architecture emerged in subsequent years. Notable examples include the Jiménez del Pulgar chalet, by Barba Corsini, and the Casa Rumeu by Correa and Milà. Recent doctoral dissertations, like the one by Marc Arnal focusing on the work of Harden and Bombelli, have delved into the study of the architecture of Cadaqués and its close relationship with the artistic avant-gardes of the mid-20th century.

Urban Development in the 1960s

With the arrival of mass tourism, starting in the 1960s the Costa Brava underwent an intense transformation: the areas around its picturesque fishing villages served as a territory for experimentation where two opposing city models converged: the garden city and collective housing. Although most of the urban developments grew up around an existing urban centre – except in Empuriabrava and Platja d’Aro – the lack of order in the initial expansions is evident: pre-existing urban cores were transformed through an increase in density and vertical growth on the seafront. Alongside the hotels and urban and suburban tourist complexes – like the Hotel Alga in Sant Feliu – the territory surrounding the urban centres was invaded by single-family housing developments on mountainous terrain – like Coderch’s unbuilt complex, Torre Valentina – and blocks of tourist apartments on the flat stretches facing the sea – like the Golf de Pals apartments by MBM. A number of luxury villas were built in places that would be unthinkable today: for example, the Casa Rozes by Coderch in Roses, the Casa Cruylles and Casa Castanera by Antoni Bonet Castellana, or the Casa Petín by Josep Pratmarsó, all of them in Begur; the Casa Sendrós by Jordi Adroer and Robert Terradas in Sant Feliu, or the villas built by Pratmarsó, in this case in inland towns.

Images of the Torre Valentina (1959), complex, a project from José Antonio Coderch (Archivo Coderch). This unbuilt complex was located in Palamón and included 131 apartments with 26 different typologies, a hotel with 80 rooms ans an underground parking dor 250 cars.

The First Environmentalists Speak Out

Although it is true that the orography of some stretches of the coast prevented the massive occupation – which did occur in other places further south, at the end of the 1960s the effects on the landscape were still very clear. Projects like the marina in Empuriabrava, which drew inspiration from the tourist complex La grande Motte by Jean Balladur and Georges Candilis in the Camargue region of France, irreparably damaged a part of the valuable ecosystem of the marshlands of the Empordà. Its system of navigable artificial freshwater canals has had an ecological impact far beyond its perimeter and led to an unacceptable change in the scale of the tourist occupation of the coast. New complexes that were intended to extend this model of tourism, like one designed for construction at the mouth of the Fluvià River, were prevented by early environmental groups.

Current image of Marina d’Empuriabrava with the with the mouth of the Muga in the foreground, in the municipality of Castelló d’Empúries.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the first ecologists made their voices heard. Around that time, Ramón Margalef, the first professor of ecology in Spain, published Nautra: ús o abús. El llibre blanc de la natura a Catalunya [Nature: Use or Abuse. A Guide to Nature in Catalonia], which became an international benchmark in scientific study and in denouncing environmental harm. In 1966, the geographer and historian Yvette Barbaza published Le Paysage humain de la Costa Brava [The Human Landscape of the Costa Brava], based on her doctoral dissertation, which became a point of reference in disseminating the human and landscape values of the Costa Brava and in denouncing the aggressions against it. Salvem l’Empordà was one of the first environmental groups organized in Spain, and it managed to obstruct the large-scale real estate developments that were pending as the transition toward a democratic regime began. Despite their efforts and interventions to restore the coastline, like at the former Club Méditerranée in Cadaqués, the progressive occupation of the territory continued until recently. The recent moratorium put into effect should bring an end to the construction of new buildings along the entire coastline of the region of Girona.

Tourist complex of La grande Motte from Jean Balladur and Georges Candilis in the Camarga (Southeast of France) 1960-1975.

Beginning in the 1960s, the coast, with its picturesque little fishing villages, served as a territory of experimentation where two opposing city models converged: the garden city and collective housing. Despite the disarray of the early attempts, specific parameters were adopted in the new fabrics, and the buildings’ relationships with their surroundings mark a clear difference from the older urban areas.

Bibliografía

AA VV, Catàleg de paisatge de les Comarques Gironines, Observatori del Paisatge de Catalunya, Generalitat de Catalunya, Diputació de Girona, Barcelona, 2014.

RAMOS CARAVACA, Carolina, “Costa Brava, los retos urbanísticos del turismo de masas. La huella de la ciudad jardín y algunos principios racionalistas en el tejido turístico de masas”, en Identidades: territorio, cultura, patrimonio 4, Máster Oficial de Urbanismo, Departamento de Urbanismo y ordenación del Territorio, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2013.

FABREGAS i BARRI, Esteve, 20 anys de turisme a la Costa Brava, La Costa Publicacions, Lloret de Mar, 2010.

TATJER, Marta, “En los orígenes del turismo litoral: los baños de mar y los balnearios marítimos en Cataluña”, en Scripta Nova, Revista electrónica de Geografía y ciencias sociales Vol. XIII, núm. 296, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2009.

BARBAZÀ, Yvette, El Paisatge humà de la Costa Brava, Vol. I, Vol. II. Edicions 62, Librarie Armand Colin, Barcelona/Paris, 1988.