Jorge Oteiza, introduction and biographical information

The in-depth study of space inherent in Oteiza’s sculptural work has significantly influenced Spanish architecture. Likewise, the collaborations he undertook with architects and his own architectural and urban works are some of the most relevant examples of the integration of the arts and architecture in the 20th century in Spain. In broad strokes, his career can be divided into two periods: the first was focused on sculptural production that delved progressively deeper into a reflection on space. The second period began in 1960 when he abandoned sculpture making to focus more directly on the reflection linked to the architectural space itself, other artistic disciplines and cultural activism.

Jorge Oteiza was born in Orio, Gipuzkoa, in 1908. He moved to Madrid in 1927 to study architecture but ended up enrolling in medicine due to bureaucratic reasons, which he soon quit. Here, in Spain’s capital, he grew more aware of the importance of his Basque identity, from left-wing social positions. After the family business collapsed in 1928, he travelled to Argentina for the first time with his family, where he worked as a waiter and cashier at a greengrocer.

Upon returning to Spain, he began collaborating with a small group of young artists in the city of San Sebastián on sculptural works influenced by Cubism and Primitivism. In 1931, he was awarded the top prize of the IX Gipuzkoa New Artists Awards. It was precisely this interest in ancient arts that brought him back to Latin America in 1934 to learn first-hand about the art of pre-Columbian cultures. Key to understanding his later career, this trip was undertaken with the young designer Cristóbal Balenciaga, whom he had met in the artistic circles of Donostia. The Spanish Civil War broke out while he was travelling through Bolivia, Colombia, Argentina, and Chile, and he opted to stay put until the war came to an end. During that time, he worked as a ceramics professor at the School of Ceramics in Buenos Aires and later in Popayán, Colombia. In South America, he met important artists of the time and wrote influential art manifestos that lay the theoretical and aesthetic foundations for his work.

In 1948, he returned to the Basque Country, settling in Bilbao. In 1951, he received a Diploma of Honour from the Triennale Milano. This recognition was followed by others throughout the 1950s that definitively venerated him as an artist of relevance beyond the Spanish borders. Upon returning to Spain, he was commissioned through a competition to work on the friezes of the new Sanctuary of Arantzazu by the architect Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, with whom he would establish a prolific professional relationship. To understand his radical intervention in the church, we must look to one of the manifestos he wrote in South America: Aesthetic Interpretation of American Megalithic Statuary. As we will see later on, in the 1950s, Oteiza also began a series of reflections through his work that lies at the heart of his contribution to contemporary art. All the while, he had been branching out with his artistic mediums and, alongside his work on sculpture and architecture, he wrote books of poetry and philosophical texts.

In 1960, he decided to definitively abandon sculpture-making to focus on architecture and urban interventions. From that point on, he boosted his public presence through the creation of avant-garde groups and important art manifestos, such as Quosque tandem…! Ensayo de interpretación estética del alma vasca (1963). He also researched the Basque language and the popular protests of his people, becoming one of its most international cultural references.

In 1988, the La Caixa Foundation and the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum organised an extensive retrospective exhibition on his work. His relations with the authorities and the Basque world of art and intellect became increasingly more complicated. His criticism of the construction of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was notorious, going as far as to say that his works would never be exhibited there. Poor relations with the Basque government also led him to donate his entire fund to the Navarrese government. This donation was conditional on the creation of a museum foundation bearing his name. The Oteiza Museum in Alzuza was the work of his good friend and collaborator, Sáenz de Oíza. The museum was inaugurated in 2003, with neither Oíza nor Oteiza living to see its completion since they passed in 2001 and 2003, respectively.

Reflections on Space: Experimental Proposition

In the 1950s, after some initial highly valuable works of art that gained international attention, Oteiza began a personal investigation under the name of Experimental Proposition (1955). He presented work under this title at the São Paulo Biennial in 1957, where he won the first prize for sculpture, an important milestone in his career. The Experimental Proposition lays the foundations for the deep spatial reflection of Oteiza’s sculptures and blurs the borders with other disciplines that deal with constructing and understanding space. It is a series of works in bent steel and stone that, along with a later series called Conclusive Works, formed the basis of his contribution to sculpture, which he finalised in 1959.

In the early 1950s, Oteiza took a radical turn in his sculpture work. Massive and monolithic sculptures, or solids, gave way to work focused on emptiness and space. He was no longer interested in reflecting on the object itself but on the space encompassed by said object or created by its negative. The mass that is sculpted is the very space contained by the sculpture; it is an “active emptying of space”.

The emptying of form moves the work from matter to energy: light is the element that fills the void and gives it form; in a way, Oteiza “frees the light” and puts it at the centre of his work. This is how he created the static and dynamic pieces known as Light Condensers, Open Formal Units and Fusion Mechanics. For the piece that he presented in São Paulo, Oteiza went one step further: he discovered what he called the Malevich Unit, which he refers to as a “small surface, the light, dynamic, unstable, floating nature of which should be understood in its full scope”. This was embodied by a trapezoid with one right, static angle and another diagonal, dynamic one, reminiscent of the irregular trapezoidal shapes that the Russian artist used in his paintings to symbolise “permanence and change”. Oteiza describes it as follows: “Malevich signifies the only living foundation of new spatial realities. In emptying the plane he left us a small surface, the light, dynamic, unstable, floating nature of which should be understood in its full scope. I describe it as the Malevich Unit”.

Unlike his previous works, with the Malevich Unit, the sculpture is created by a plane, a trapezoidal figure created from a square or rectangle that has lost two of its right angles and, therefore, has one stable element – the right angle – and one moving element – the diagonal –, which Oteiza used in planes and curves, and solid and empty areas. The sculpture became a sequence of “absolutely secondary forms” that define a space.

To a great extent, it was this reflection at the IV São Paolo Biennale – held only four years after the Kassel Documenta –, that laid the foundations for Oteiza’s legacy in the field of contemporary sculpture and forged the connection with architecture through a methodology of reflecting on empty space.

Collaborations with Architects

There is extensive literature highlighting the important “architectural” nature of Oteiza’s work, as well as his collaborations in specific works of architecture and the influence that his work had on other architects, such as Rafael Moneo.

From an artistic point of view, Oteiza became aware of the need to inhabit art, both physically and spiritually. This concept was already present in his South American manifestos and, later, when his reflections move towards the void, his interest in architecture was almost inherent to his formal investigation. After all, architecture is the only artistic expression that is meant to be lived in, and it is only in the voids created by the work in which we can live. The piece is no longer intended for the viewer but for the inhabitant. Therefore, the connection between architecture and Oteiza’s work is almost fundamental and inevitable, in a sense.

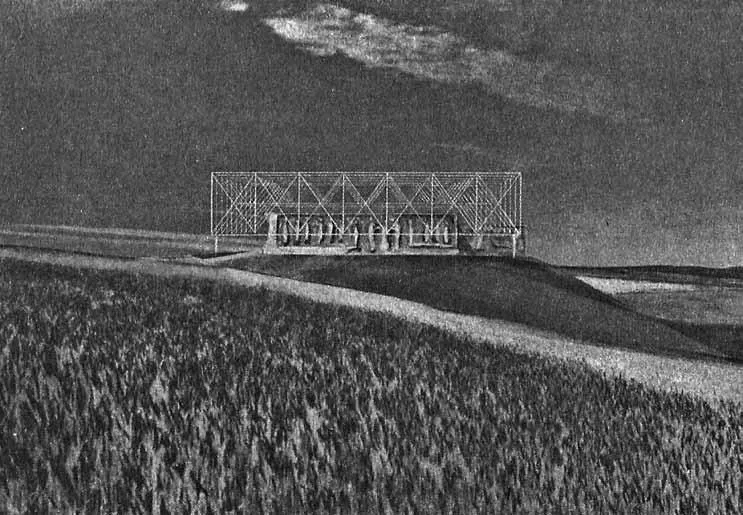

He collaborated in the world of architecture many times throughout his career. He participated in the competition for the José Batlle y Ordóñez Monument in Montevideo with Roberto Puig. He also participated in other competitions with the architect Juan Daniel Fullaondo, such as for the San Sebastián cemetery. His most intense connection to architecture came through Sáenz de Oíza. In 1954, the project for a chapel on the Camino de Santiago by architects Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and José Luis Romaní was awarded the National Architecture Prize, even though it was never built. The chapel was integrated into the landscape through a meandering structure from which sculptural friezes by Oteiza would hang and large metal meshing would be spread. In 1955, Oteiza completed numerous figurative and abstract relief studies for the Universidad Laboral de Tarragona in which he explored the technique of debossing. Meanwhile, he participated with Oíza in the construction of one of his most acclaimed works, the new Sanctuary of Arantzazu, and collaborated on the work that Miguel Fisac was carrying out for the Dominican Fathers of Valladolid with a sculpture for the apse of the church.

In 1955, Oteiza also took part in what would be the first work by Rafael de La-Hoz Arderius and José María García Paredes: the Córdoba Chamber of Commerce. The hand of Oteiza is especially visible in the spectacular foyer where, in addition to several sculptures, he designed a unique piece: a cantilevered counter fully integrated into the architecture and decorative programme of the space.

From 1957 to 1958, Oteiza designed what would be his home and workshop with the architect Néstor Basterretxea. The construction is on avenida de Iparralde in Irun and is currently under restoration after having been abandoned. Two sculptures by the artist can be found on this very avenue: the stele on the Puente Internacional bridge and the sculpture Empty Edge, in front of the Palace of Justice.

In his more urban works, such as in 1955 on the façade of the Livestock Artificial Insemination Institute, his art remains subject to the architecture, aimed at decorating and not daring to interfere in the urban space. This would begin to change after 1960.

Sculpture from Oteiza in the façade of the Instituto de Inseminación Artificial en la Ciudad universitaria in Madrid, 1952.

One of Oteiza’s great patrons was the Huarte family. When the family construction company was working on the Nuevos Ministerios complex in Madrid, they commissioned Oteiza to create a series of murals. They set up an on-site workshop for him where he could also carry out personal work. According to some sources, it was through mediation by Oteiza that the Huartes hired Sáenz de Oíza for such important works as Torres Blancas and the Huarte house itself. Although there is no documentary evidence, some critics have observed a clear influence of Oteiza in these works through the compositional play of solids and voids.

Architecture and Urban Work

In Lima in 1960, Oteiza announced that he had reached the end of his sculpture work and had decided to leave it behind to explore other forms of reflection in which architecture and the city would occupy a central role.

A variety of circumstances led him to this decision. Three years earlier, in 1957, he wrote several preparatory texts for two works that are clearly linked to architecture and urban works: Propósito Experimental Irún and Estrategia inicial: del techo de Irún al muro de la plaza Colón. These texts accompany a series of interventions in which the sculptor’s participation is presented as an architectural performance: a mural on the ground floor of some houses in Irun and two friezes in hotels, one in Plaza Colón in Madrid and the other in Bilbao. In 1958, Oteiza travelled from Irun to the World’s Fair in Brussels. There, he discovered important architectural and sculptural references that deeply influenced him.

Studies from Oteiza for the unbuilt bas-relief of the Babcock & Wilcox building in Bilbao. The building, located in the Gran vía in Bilbao, was built in 1965 by Álvaro Líbano and José Luis Sanz Magallón.

In this period, he built lesser-known works in which the landscape played an essential role. This is the case of the monument chapel in honour of Aita Donostia, a musician and priest who died shortly before the Expo and commissioned Oteiza himself, along with the architect Luis Vallet.

In his final years of artistic creation, he dedicated his work to architecture. Later, numerous sketches, chalk drawings and small models have come to light that, today, are no longer considered preparatory documents but works of art in themselves.

La Basílica de Aránzazu

The Sanctuary of Arantzazu marked a turning point in Oteiza’s relationship with architecture. On the one hand, it was his first collaboration with Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza and the start of a prolific professional relationship. On the other, his interventions in the sanctuary inaugurate a series of works in which Oteiza goes beyond a purely decorative and superficial vision and delves into reflections on architectural space itself.

In 1950, after the old church was destroyed in a fire, a contest was held and the winners were the architects Luis Laorga and Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza. Oteiza, who was very active in promoting and revitalising Basque art at the time, was called upon to collaborate in the sculptural decoration of the sanctuary. His intervention took on a symbolic nature and received acknowledgement that few of his later architectural works would achieve.

In a remote area of the Oñate mountains in Gipuzkoa, surrounded by a rugged landscape of great beauty, stands the Franciscan sanctuary that has guarded the image of Our Lady of Arantzazu for more than 500 years. The building, with its vehement presence and the radical use of raw materials in allusion – according to the architect himself – to the ancestral character of the place, acquires an almost geological character.

Oteiza’s work, specifically the frieze of the apostles, is also a reflection on the megalithic art and pre-Columbian sculptures that he had encountered on his recent trip to Latin America. His intervention was controversial from the start. The heterodox iconography of the frieze of the Apostles – he portrayed 14 – as well as its aesthetics – too avant-garde in the opinion of ecclesiastical institutions – led the Church to halt the placement of the pieces considered sacrilegious. It was not until 1968 that the ecclesiastical veto was lifted and the frieze of apostles and the image of the Virgin with her dead son at her feet were put into place. This is why the great influence of this work on young generations of Basque artists comes after the time of its conception.

One of the keys to understanding the importance given to Arantzazu in contemporary Basque culture is the number of artists who worked on it, many of them young people who would later become established artists. The iron, geometric doors of the temple by a young Eduardo Chillida made a deep impression on Oteiza.

Legacy

At the end of his career, Oteiza resumed his relationship with Oíza and, together with Juan Daniel Fullaondo, submitted a risky proposal for the competition for the renovation of the Alhóndiga de Bilbao, another project that would never come to fruition. During an earlier visit to the building, in 1988, the news that the sculptor had received the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts was made public. Oteiza’s improvised statements to journalists waiting for him at the exit exemplify the pessimism and disappointment that marked the last years of his life: “This town is culturally ruined. The Basque Country has more than enough energy to get ahead in politics, the economy and industry. But Basque culture has been corseted, compartmentalized and stifled by our politicians. Magnificent projects could be done, but they are nothing more than small patches. An overall revival of our culture is now impossible”.

The creation of the Jorge Oteiza Museum Foundation in 2003 in Llodio has been key to maintaining and understanding the artist’s work, as well as deepening our knowledge of and sharing the impact he had on contemporary Spanish and international art. Despite the bias that it would have caused the artist, it was necessary to create a reasoned and definitive catalogue that would allow new generations to understand the breadth and depth of his work.

Bibliography

BADIOLA, Txomin, Oteiza. Catálogo Razonado de Escultura, Editorial Nerea, Donostia, 2019.

MORAL ANDRÉS, Fernando, Oteiza. Arquitectura desocupada. De Orio a Montevideo, Cátedra Jorge Oteiza, Universidad Pública de Navarra, Pamplona, 2016.

ÁLVAREZ MARTÍNEZ, Soledad, Jorge Oteiza: una experiencia escultórica singular y genial, Publicaciones Menhir, Bilbao, 2004.

de Anasagasti, Pedro, “Oteiza en Aránzazu”, en ARA. Arte Religioso Actual, Año VIII núm. 31, Guipúzcoa, 1972.

AA VV, “Concurso de monumento a José Batlle en Montevideo”, en Arquitectura 6, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos, Madrid, 1959, pág. 17-23.