“Today, in the machine age, each new object is the immediate expression of progress; every part and every new element is exactly adapted to a purpose, and anything useless is disregarded”

Miguel López González, 1935

Miguel López González (1907-1976), a member of GATEPAC, earned his degree from the Barcelona School of Architecture in 1931; he then moved to Alicante where he set up his practice, combining it with the position of municipal architect. From the beginning of his professional career, he embraced the axioms of the modern movement, picking up the currents of the European avant-garde. His architecture uses minimal volumes; they are simple, associated with a single use, and they follow a rational, decisive and radical geometry, unusual in Spain at the time. The blank walls with smooth, taut surfaces made a splash in the society of his time due to the sobriety of their forms without historicist references. Attuned to technological and material innovations, the architect’s production, spanning almost half a century, is remarkable within the architectural panorama of Valencia, along with that of Luis Albert Ballesteros, and he stood out on the national scene as a “modern architect from the periphery”, coherent in his functional and formal approaches. He is responsible for the transformation of Alicante and the introduction of modern architecture in this part of the Mediterranean. Almost 20 works from his career, still in good condition, are included in the Iberian Docomomo registry (hereafter: “the registry”). His professional career can be divided into three periods: the first two lasting a decade and a third spanning more than two, although the dates are not mutually exclusive.

Early Modernity: 1932-1942

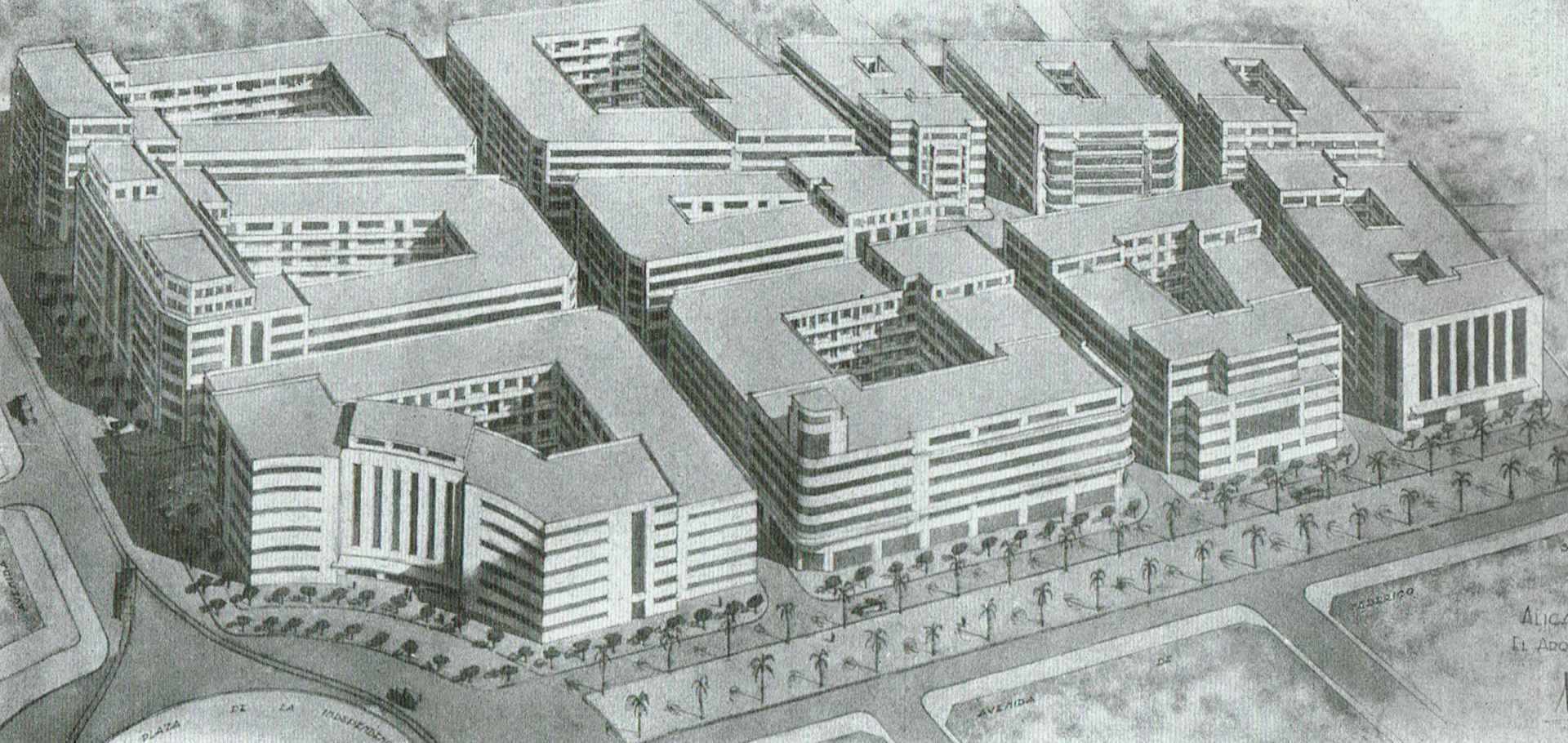

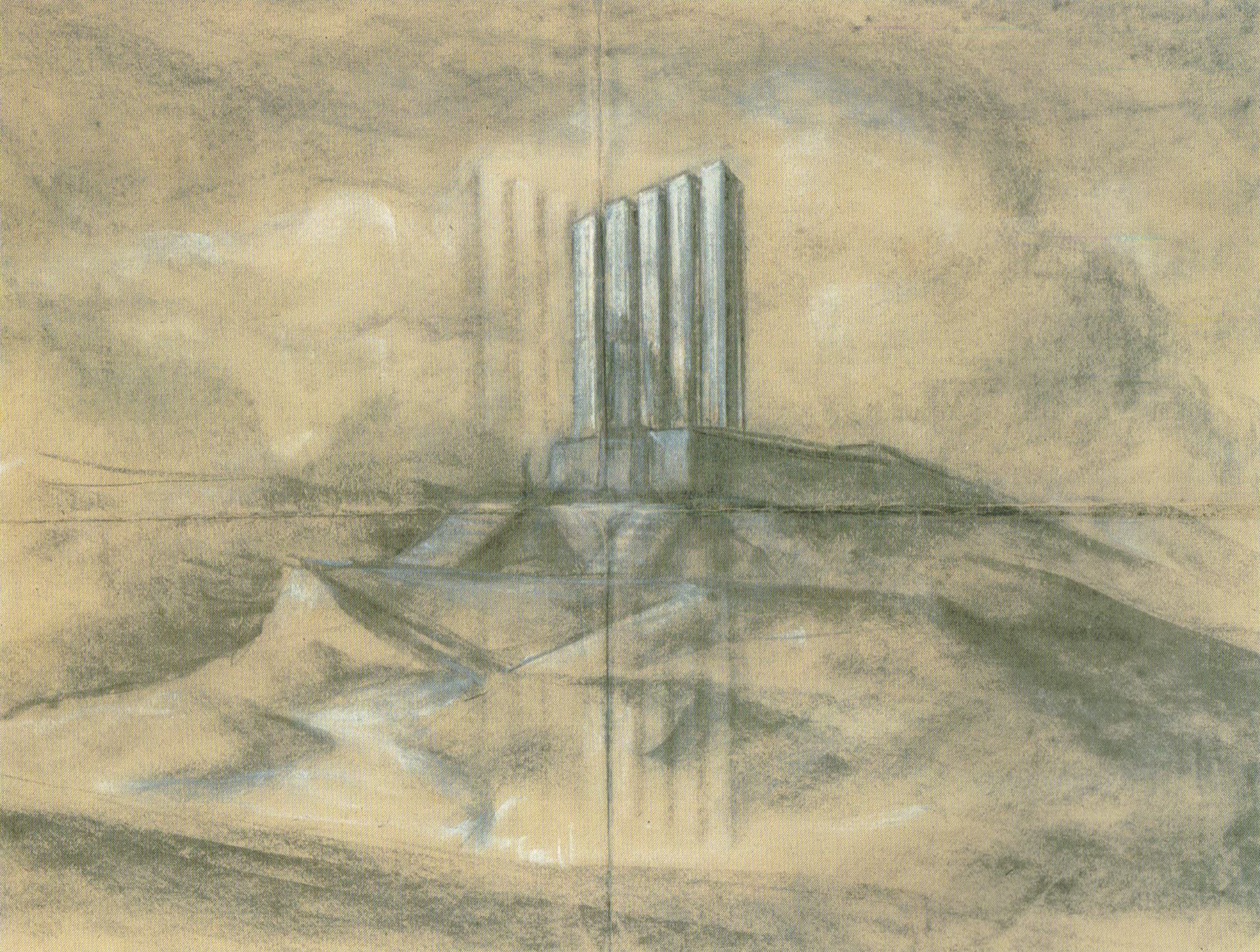

Perspective of the new urban land use plan for the Montanyeta area, Alicante, 1932

Source: Secretaría Municipal, “Memoria del Ayuntamiento de Alicante del 15 de abril de 1931 a diciembre de 1932”. Alicante City Hall, 1933

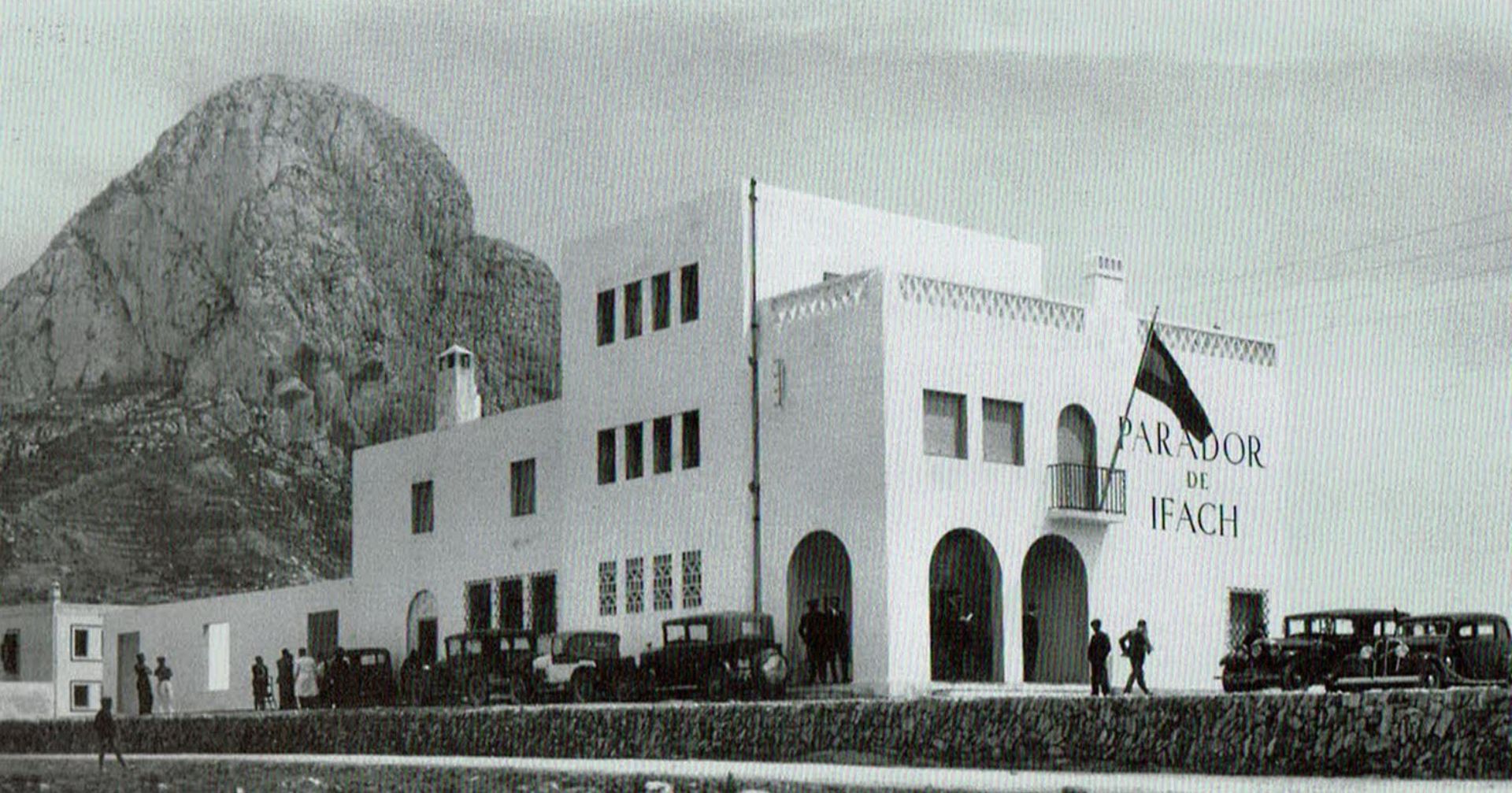

Miguel López González, a native of Valencia, became a full member of GATCPAC in August 1931 after graduating from the Barcelona School of Architecture two months earlier, where he had made friends with Josep Lluís Sert, Josep Maria Soteras, Josep Torres Clavé and Ricardo Bofill. He was 24 years old when he arrived in Alicante to manage a family business, and he decided to stay. He joined the City Council as an assistant architect, a position he occupied throughout his life except during the post-war period, when he was a victim of retaliation. A first project from 1932, designed from the municipal office together with the engineer Sebastián Canales, offers a clear example of his principles. It was the new urban land use plan for the Montanyeta area, a neighbourhood of run-down housing located on the small hill wedged between the historic centre, the city walls and the 19th-century expansion. The aerial perspective announces a new way of building the city: residential complexes that are articulated around large courtyards for views and ventilation, defining blocks formed by two bays or in a ring. The exterior and interior façades use an abstract language based on clean surfaces with long cuts traced into them by the window frames, aligned with the modern architecture coming in from Europe, using perspective drawings as advertising for the new political times: precise, clean and honest. The plan returns to the tradition of dense blocks, limiting their built depth and incorporating the novelty of a striking urban image. In 1932, López González drew the Parador de Ifach (published in the Revista Nacional de Arquitectura in 1950), now unrecognizable. A hotel with just a few rooms that was expanded over time, it is formed by a solid two-story white prism, intersected by a semi-cylinder and a terrace overlooking the sea. It is surrounded by a wall of arches, where a certain vernacular architecture approaches some of the formal characteristics of the continental avant-garde, which Mercadal would have called Mediterranean architecture.

Picture after completion (1950′) of Ifalch Parador, Calpe, 1932-ss

Source: Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 127, 1952

During this period, and well into the 1940s – since the cultural mandates of the Franco regime were not immediately enforced in the provinces – his architecture, abundant in residential buildings in Alicante, is characterized by taking up the aesthetic, functional, and technical characteristics of interwar modernity, expressed through simple volumes, a transparency of programme, and frame structures. The envelopes of his bourgeois buildings, between party walls, surprised society with the bareness of their white or soft-toned plaster façades, entrusting their plasticity to the play of light and shadows coming from the projecting elements (overlooks, balconies, terraces, canopies, pergolas, etc.) and the openings with flush frames that incorporated roller shutters, making their elevations even more weightless: through the use of pillar and girder structures the façades were freed from their load-bearing role. Two formal variants can be seen within this production: a more “prismatic” group, with emphatic volumes and the predominance of walls, that would include the buildings Borja (1935-1936), Barón de Finestrat (1939-1941) and Rambla Méndez Núñez (1941-ff., with a design by Manuel Ignacio Galíndez Zabala), and another more “expressionist” group (inspired by the poetics of Mendelsohn), with the prominence of overhanging volumes, that would include the buildings Galiana (1934-1936), Roig (1935-1936) – a twinned cylinder on the corner of a parallelepiped – where he installed his studio, the Adriática (1935-1936) and Montahud (1939-41); all of which are included in the registry. The exterior image of those final four buildings is unified and powerful thanks to the façades that overhang the street, characterized by the overlapping of the solid horizontal bands of the walls alternating with the continuous, dark lines of the horizontal windows letting in abundant light and air, and capturing views over the urban landscape.

Perspective of the Southwest Market, Gravina Street, Alicante, 1941 (collaborator: Miguel Abad Miró, Architecture student)

Source: Archivo Histórico de Alicante

Another of the fronts in his work was that of social architecture, specifically in programmes related to education and healthcare, supporting the policies implemented by the Second Republic, as well as small markets for various neighbourhoods; a majority of those designs remained only on paper. One example is the Sureste market on calle Gravina from 1941 – on which Miguel Abad Miró collaborated as a draftsman – with its double-height central space covered by parallel, shallow reinforced concrete vaults. López González designed various school complexes with housing for teachers, including those in the neighbourhoods of Carolinas, Benalúa and San Blas in Alicante, as well as those in Sax (1934) and Santa Pola (1935) in the province. In all of them, he experimented with the new typologies of free-standing or L-shaped blocks, where the educational programme is articulated through the circulations because utility was a fundamental principle in his work. However, the most rational projects associated with the axioms of the new objectivity were designed in this decade and built in the next. We are referring to the Instituto Provincial de Higiene (1935-1945) and the Sanatorio y Casa de Reposo Virgen del Socorro (1942-1948) – published in the Revista Nacional de Arquitectura in 1950. Both are in the registry; the first was a public initiative and the second private. In the latter case, according to the architect, there was a focus on “Distel’s three principles: 1) Utility, 2) Flexibility and 3) Economy.” However, due to their late execution, under unfavourable conditions with regard to certain aesthetics of utility, we understand these two works as a resistance to the imposition of returning to the architecture of Spain’s imperial past. Thus, we will analyse them in the context of their time: that of autarky.

It is clear that, in just 10 years, through his designs and built proposals, Miguel López González had renewed the urban image of Alicante through several residential buildings, various public facilities, some small commercial premises, and even a couple of flour factories: Cloquell (1936-ss) and Bufort (1941-ss), the latter of which is included in the registry. He did this precisely by removing all added decoration from the buildings and resorting only to essential volumes (each with its own use), smooth surfaces and clean lines, whether straight or curved, all governed by a rational geometry: form was, therefore, subordinated to function, with no a priori features. The architecture of the modern movement had arrived in the eastern provinces and had come to stay, beginning to cement a new tradition: aesthetics without a functional foundation were meaningless.

Autarkic Resistance: 1942-1952

On 30 March 1939, the Nationalist troops entered and took Alicante, the last capital of the Second Republic, but it would still take some time for the implementation of nostalgic cultural orders (academist compositions and classicist languages) in private architecture to take hold under the new regime, which rejected modern architecture as foreign. The dictatorship, with ties to European fascism and politically and economically isolated from Western allies, opted for autarky and isolation. The victors were quick to honour the victims from their side: monuments and crosses were erected across the peninsula in the five years following the end of the Civil War. Miguel López, who designed several of these landmarks before being retaliated against, took special care to simplify them to ensure their proper interpretation. The first was the Monument to the Fallen for Spain and for the Homeland (1939), located on one of the city’s boulevards, for which he designed a stylized Latin cross with the lower arm braced by an arch; the whole, clad in stone, needed no framing. The second, the “Monument to the Fallen of La Vega Baja”, from 1941-1944 was more ambitious. On the outskirts of the city, its sculpted base, completed together with the sculptor Daniel Banyuls Martínez, consists of five vertical prisms in an allegory of the arrows in the motif of the Falange, standing on a platform from which to harangue the crowds gathered around. Both monoliths – given new meanings – symbols of the victory of the rebel faction, take their inspiration from Nazi propaganda and Italian fascist architecture, showing echoes of Terragni in their formal abstraction, geometric rigor and pursuit of timelessness.

Sketch of the Monument to the Vega Baja Heroes (Falangists) in the area of Agua Amarga, Alicante, 1941-1944, together with Daniel Banyuls Martínez, esculptor

Source: M. López González Professional Archive

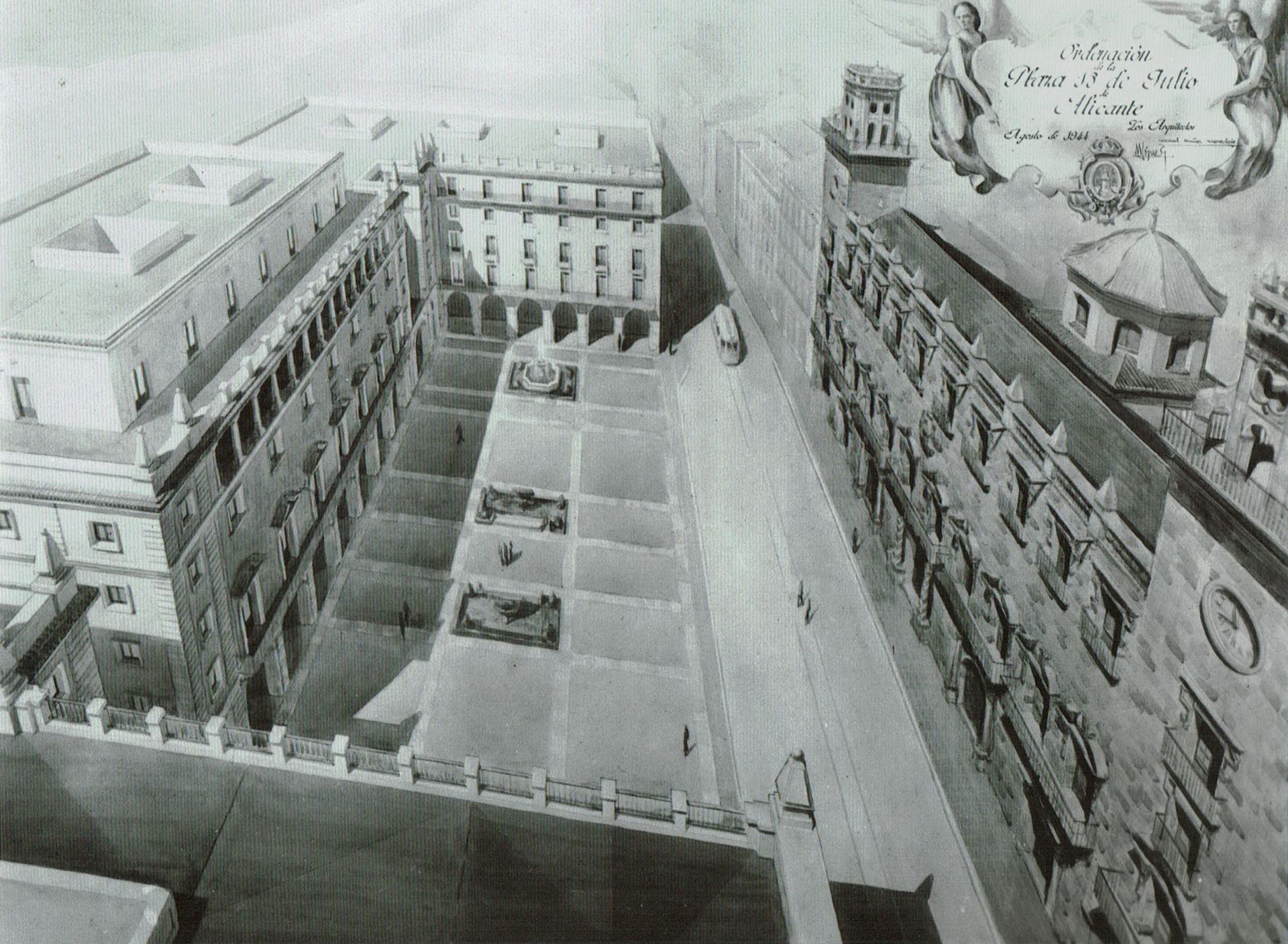

Miguel López was removed from his post as a municipal employee from 1942 to 1948, although he was able to continue practicing through private commissions, which he adapted to the tastes of the early Franco regime: pilasters, cornices, balustrades and pinnacles began appearing in designs and built work. From this somewhat anachronistic production, it is worth highlighting both the Paseíto Ramiro buildings (1943) and El Águila (1948), as well as various preliminary projects for bourgeois buildings, bank offices and insurance companies in Madrid. The architect’s relationship with the capital arose from his friendship with Manuel Muñoz Monasterio, with whom he formed a tandem for the 1944 national competition for the Planning and Remodel of the Plaza del Dieciocho de Julio (current Plaça de l’Ajuntament). His winning proposal for that competition laid out a “Spanish main square”, with a regular modulation and a rectangular footprint (deviating from the Valencian tradition) bordered by a uniform portico around the perimeter under the new residential buildings and the Court buildings, which created a public square suited to “civic concentrations”. There are no trees to “block the view of the main focus”: the historic baroque Town Hall. A selection of the drawings was printed in the Revista Nacional de Arquitectura in 1945, notably, the perspective drawing with three vanishing points.

Aerial perspective of the project area for the Remodel of the Plaza del Dieciocho de Julio (now Plaça de l’Ajuntament) in Alicante, 1944, together with Manuel Muñoz Monasterio (collaborator: Miguel Abad Miró, Architecture student)

Source: Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 43, 1945

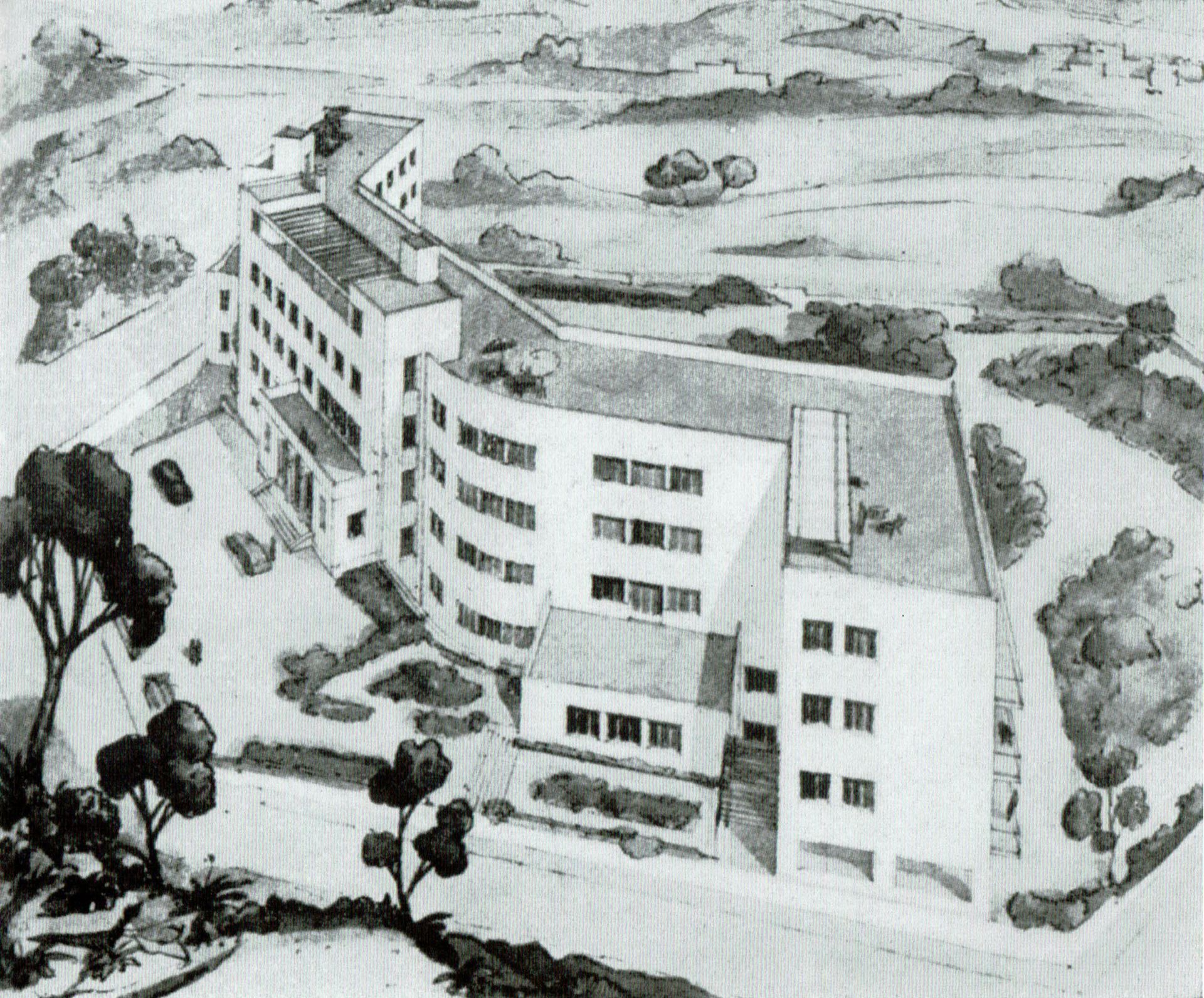

On the other hand, as we stated earlier, not all of his production is associated with historicist references: his intellectual resistance shows through in certain projects, such as the Instituto Provincial de Higiene (1935-1945) and the Sanatorio Virgen del Socorro (1942-1948), both in the registry. Both health centres were designed as white volumes – using white as an allegory for hygiene and, therefore, for health. They are well oriented in terms of sun exposure as a result of the organization of the programme. The former uses a metallic structure to resolve the volumes of the L-shaped floor plan, and the latter uses parallel load-bearing walls, justified by their lower cost, to articulate the three prisms with curved pieces that generate an organic quality and provide panoramic views over the garden and the sea in the distance. Precisely, when the Sanatorium was published, the author took the opportunity to explain the ideas that went into its conception: “the criteria adopted […] were those marked by European trends, taking as an example […] the Hospital Beaujon in Paris, which […] is characterized by […] the predominance of the horizontal dimension over the vertical; thus patients are given direct access to the garden.” Furthermore, “another of the basic conditions [was the] linear floor plan with load-bearing walls running laterally, [which provides] enough flexibility to allow for possible future modifications and extensions.” In fact, “the form of the floor plan is a direct consequence […] of its function, […] structured along corridors that, in turn, are connected vertically by stairways”, a feature that he describes using a circulation diagram in an axonometric projection that is reminiscent of Gropius’s design for the Bauhaus.

Aerial perspective of the Sanatorio and Casa de Reposo Virgen del Socorro in Alicante, 1942-1948 (collaborator: Miguel Abad Miró, Architecture student)

Source: Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 101, 1950

From the end of this decade, it is worth citing some of the housing developments subsidized by the state in which the architect participated, along with other colleagues, including the single-storey semi-detached houses for Valenciana de Cementos in San Vicente (1944) and the Colonia Rabasa in Alicante (1945-1955), in which traditional architecture is refined in its types and forms. Other examples include the housing blocks for the Pla del Bon Repòs (1950-ss), San Francisco de Asís (1953-ss), Sagrada Familia (1951-ss) and División Azul en Alicante (1952-ss), the latter developed by the INV and included in the registry. Containing 532 units in five-story blocks without courtyards, and resolved with minimal programmes, they were an extension of the peripheral neighbourhoods intended for families of immigrants who had left the countryside for the city, and they served as a new laboratory for exploring the principles of the Modern Movement applied to collective residential uses. These designs presaged a new phase in the architect’s career.

Reuniting with the International Community, 1952-1976

The international rehabilitation of the Franco dictatorship was a slow process that culminated in the 1950s with the signing of the Pact of Madrid with the United States (1952, when ships from the Sixth Fleet arrived in the port of Alicante) and the Concordat with the Holy See (1953), along with Spain’s entry into the UN (1955) and the IMF (1958). The country, little by little, began to change, laying the foundations of the future welfare state. Housing, schools and hospitals were among the political priorities, and Miguel López returned to his modern principles with the new times that were beginning in 1953, embracing the currents of international architecture, now with improved technical quality, better materials and framed structures, leaving behind both historicist references and the naive mechanist universe. Two pairs of projects, contrasting in terms of their representative quality and scale, are early evidence of this turn, one centred on industry and the other on urban elements. The pair of factories, Aluminio Ibérico (1953-1956), included in the registry, and Manufacturas Metálicas Madrileñas (1954-ff., demolished), located next to one another on the outskirts, emerge as a paradigm for the large scale. The former, which had the precedent of a project abandoned by Cano Lasso, resolved 50,000 m2 of warehouses with serrated concrete frames, fitted with skylights, and bays of up to 25 metres. The other pair, the Sandoval petrol station (1950-1953, demolished) and the new bandstand, derived their expressiveness from the singularity of their exposed concrete structures. In fact, the bandstand or “Concha” (shell) – a nickname related to its shape reminiscent of an open bivalve – also in the registry, is a cantilevered slab with a graceful organic profile in plan and section that became an icon. It was the starting point for the remodel of the Explanada promenade (1957-1959), which López González designed as a municipal employee together with Alfonso Fajardo Guardiola. The Explanada became a symbol of the city’s cosmopolitan nature and its openness to tourism with its undulating pavement in waves of three colours – cream, red and black: a Roman mosaic inspired by the historic Copacabana promenade in Rio de Janeiro and works by Niemeyer.

Once again working at the municipal office, and teamed up with Francisco Muñoz Llorens, architect and deputy mayor under Agatángelo Soler (1954-1963), López González designed various facilities, in addition to the Concha and the Explanada (a firehouse, a slaughterhouse, etc.). He also worked on the master plan for Alicante in 1958, in keeping with the new Land Use Regulations of 1956, which applied zoning criteria, overall systems, and uses that would ultimately usher in an era of excessive building heights and density. The first high-rise residential buildings began to be built following modern pre-war principles (distribution, ventilation, views and metallic or concrete structures), incrementing the surface area dedicated to terraces and using new materials: ceramics and tile, natural stone and exposed brick, wooden roofs and panels. Examples that illustrate this change in scale and material quality include the residential property on the corner of calle Duque de Zaragoza and avenida Constitución (1957-ff), characterized by the use of green tile, and the residential building on the corner of Plaza Calvo Sotelo and Federico Soto (1956-1958), included in the registry, which, with its asymmetry, deep terraces, pergola and solid vertical walls (inspired by Gutiérrez Soto), decidedly opts for the abstract languages suggested by industrial architecture. In the 1960s, Miguel López’s residential architecture, always orderly and elegant even in social housing, followed along with the typical international style, comfortable and commercial, since the programmatic principles of the interwar period had been standardized upon being incorporated into the building code, appearing, in most cases, in volumes composed of superimposed layers that seem to be floating.

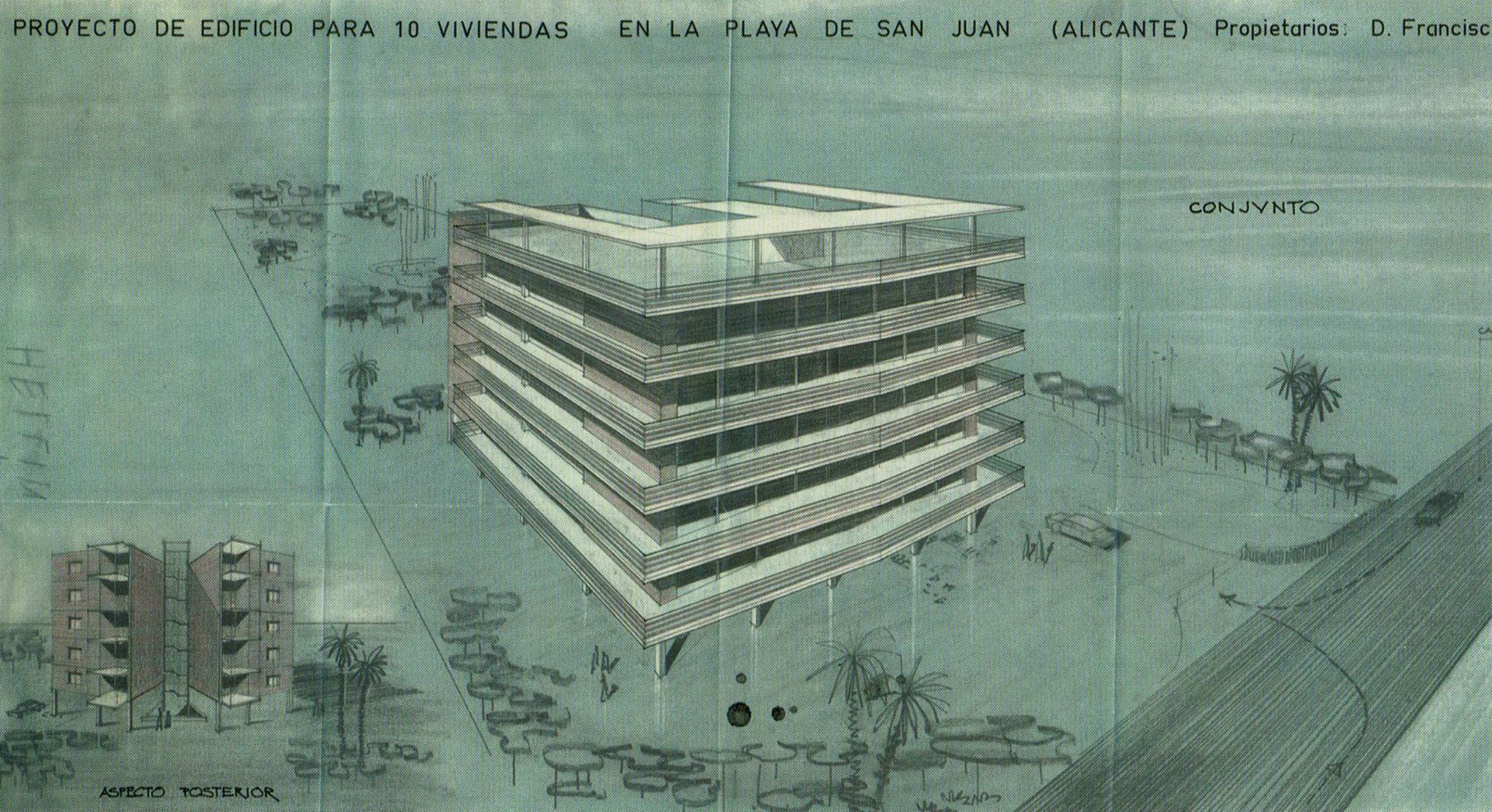

Perspective of Holliday block buildings for Francisco Hellín, in Playa de San Juan, Alicante, 1962-ss

Source: M. López González Professional Archive

Almost at the same time, in 1958, and with the precedent of having adapted, together with Muñoz Monasterio in 1953, the plan for Playa de San Juan (almost 10 km2), which had been developed by Muguruza Otaño in 1933, López González designed the first estate for that immense “holiday city” (which Guardiola Gaya took over a year later), authorizing open block housing developments to replace the bourgeois “little hotels”. The middle classes would be able to occupy seaside flats, and the culture of mass tourism began to take off. These open block buildings – hygienic, sun-filled and well-ventilated – on plots equipped for summer leisure (with gardens, swimming pools, play areas or sports courts, and parking), are exemplified by the tourist complexes in Playa de San Juan, as well as the four residential blocks for the Constructora del Sudeste (1958) and the block for Francisco Hellín (1962). In these properties, the terraces – conspicuously horizontal and lightweight – are understood as one more room where people can enjoy spending time with family during the summer: the tourist habitat became a new testing ground for minimal housing. The principles of the modern movement were easier to implement with the new functionalist urban development intended to receive the flows of tourists and residents. For the same purposes, hotels and residences for employees of large companies were also being planned all along the coast. A catalogue would include the Hotel Playa in Playa de San Juan (1952-1958), published in the Revista Nacional de Arquitectura, the Hotel Hipocampos (Calpe, 1955-ff.), the centre for workers at the Bank of Bilbao (Villajoyosa, 1958, demolished), and the luxury accommodations Montiboli (Villajoyosa, 1966-68). The latter, situated on a promontory above the sea and adapted to the terrain with a certain sensuality, referenced “the local Mediterranean character” through a mimetic reproduction of historical popular architecture but nonetheless earned López González the national award from the Ministry of Information and Tourism in 1972.

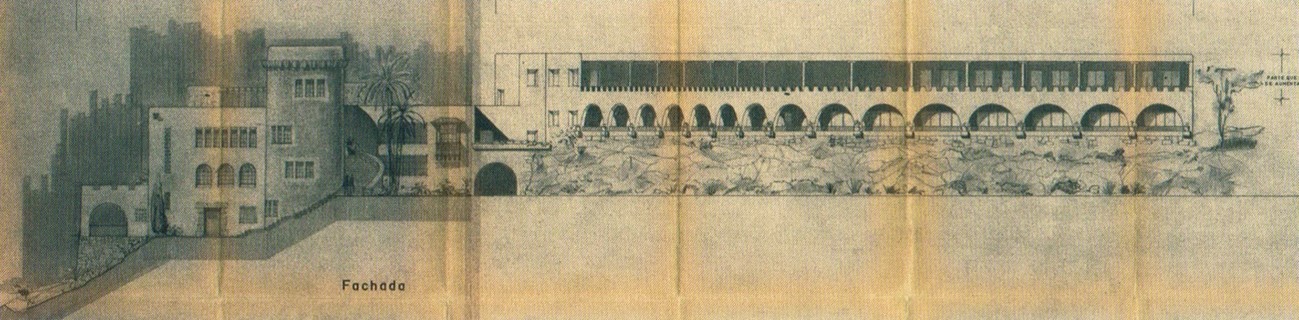

Elevation of the Hotel Montiboli after the extensions, 1966-1968, Villajoyosa, Source: M. López González Professional Archive

His institutional architecture, mainly associated with education and the promotion of religious institutions, was much more innovative and experimental. Spain entered into a close relationship with the Catholic church in 1953, and that same year legislative reforms were undertaken for primary and secondary education and vocational training. In addition, many public school projects dating from the Republican era were completed during this period. Three new works, included in the registry, reveal this evolution: the Colegio de los Jesuitas (1955-sq.), symmetrical, using a vocabulary of vertical openings but with rooms topped by a series of concrete vaults; the Casa Sacerdotal (1958-1963) defined by three prisms, with different dimensions and uses, sitting above a landscaped site; and the Colegio Sagrada Familia (Elda, 1962-1967). In the latter, which was based on the symmetrical layout of the Colegio de Huérfanos Ferroviarios (1952-ff., in collaboration with Francisco Alonso Martos) and the Juniorado in Guardamar (1960-1963), the Y-shaped floor plan is articulated by a helical ramp, like a hinge, located at the intersection of the three wings that are specialized by uses: education, events and student housing. Each of these designs include a chapel, as a singular space, which is always laid out as a well-defined container with perpendicular edges – a vertical pavilion. Using a renewed religious iconography (windows, finishes, furniture and artwork), they form modern sacred spaces characterized by a somewhat industrial asceticism that integrates the arts, for which the architect collaborated with painters and sculptors of national or provincial relevance, including José Luis Sánchez, José María de Labra, Francisco Farreres, Esteve Edo and Antonio Carrillo, among others.

One of the initial perspectives for the Hotel Gran Sol, Alicante, 1962-ss

Source: M. López González Professional Archive

To close out this final period of almost a quarter century, it is worth mentioning the first skyscraper built in Alicante: the Hotel Gran Sol (1962-ff), on a corner in the historic centre, a vertical landmark with a square floor plan, with a 1:6 proportion between the base and the height, with two slender 30-storey party walls (painted by M. Baena). It was designed using photomontages and built using metal profiles and a curtain wall on its three mezzanine levels and the final three floors. The skyscraper was the subject of controversy in the media: detractors denounced the lack of respect for the urban surroundings and the excessive density, while defenders argued for its modernity and how it represented progress, issues already subject to debate in the critical sessions organized by the Revista Nacional de Arquitectura and the journal Arquitectura between 1955 and 1960. To some extent, the dialogue between the renovated Explanada promenade, 500 metres long, and the Gran Sol hotel, 100 meters high, offered a modern reinterpretation of the historical relationship between tower and square, now on a metropolitan scale, incorporating the profile of the Gran Sol into the skyline of the seafront.

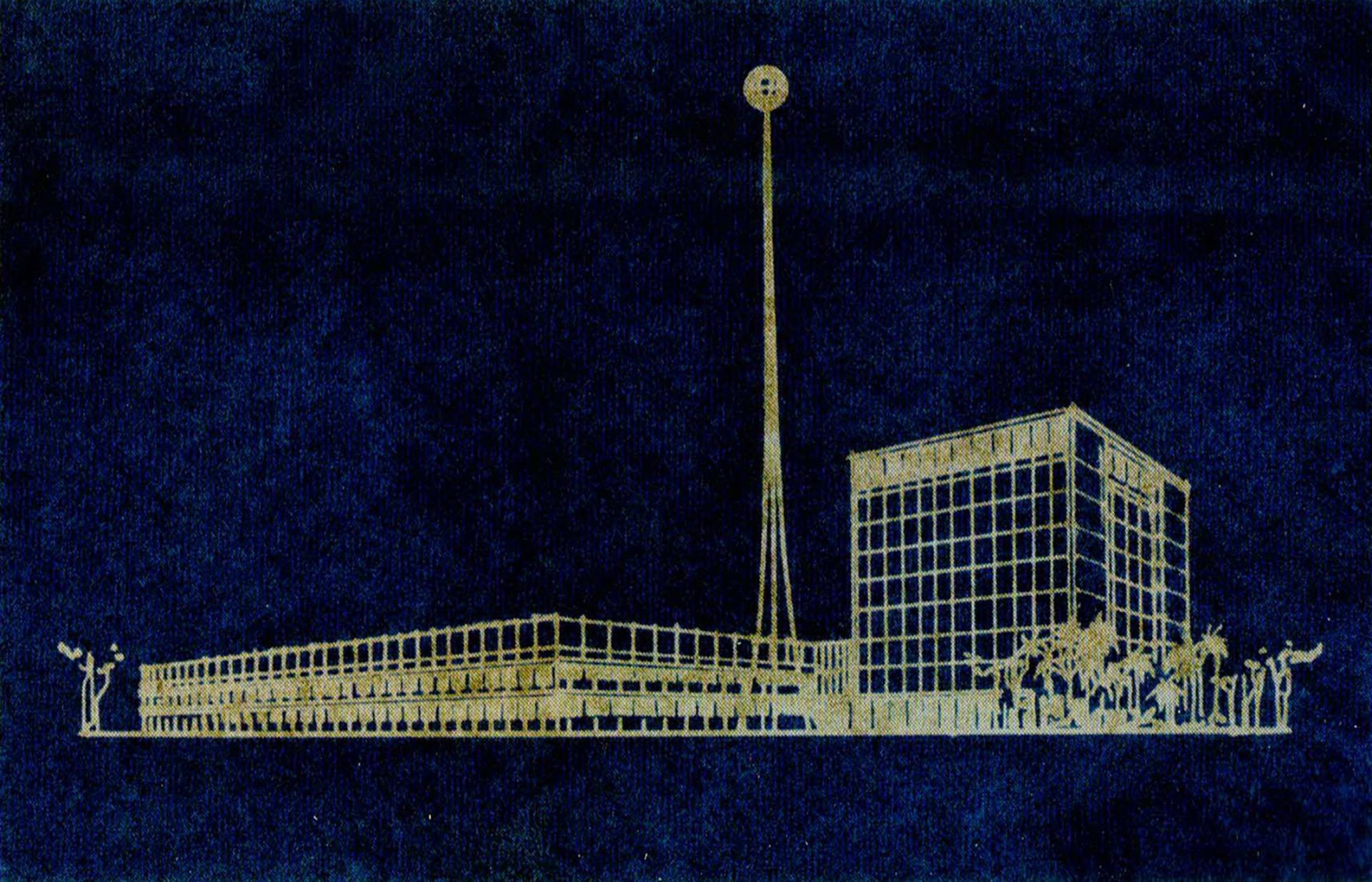

Perspective of the area of the Fair of Footwear and Related Industries (FICIA), Elda, 1963-1966

Source: M. López González Professional Archive

A shorter skyscraper (designed to have nine floors, although only five were built), for offices, event halls, a hotel and cafeteria, and a horizontal pavilion (two storeys) built as a counterweight, for the exhibition of products, were the two types used for the International Fair of Footwear and Related Industries (FICIA) (Elda, 1963-1966): the tower as an urban landmark and the pavilion as a covered plaza, along with a monolith serving as a broadcast antenna. The exposed brick surfaces and the curtain walls in both volumes demonstrated an architecture of Miesian descent. As was the case throughout his career: simplicity, austerity and an economy of means all contribute to an architecture that is adapted to a strict and forceful modernity.

A Final Consideration: Regarding Modernity

Miguel López was an architect faithful to the modern principles he picked up during his education (and kept current via books and magazines) and put into practice throughout his career, which was doubly peripheral in Alicante due to its geographical and cultural conditions. Despite this disconnection from the centres of political, economic and academic decision-making, we can consider our protagonist, due to his professional coherence, as one of the “founding fathers” of the new tradition of modern architecture: one that takes people into account and that responds to the principles of hygiene, functionality, advanced techniques and formal refinement, without neglecting the construction budget. As an architect, López González focused more on volumes than on spaces – as evidenced by the drawings that have been preserved, in which exterior perspectives abound – as a result of volumes being designed for exclusive uses. There are few conic perspectives of the interiors, which emerge as immediate enclosures inside the containers due to the directness of the exposed frame structures. Miguel López González was also influenced by Le Corbusier’s statements from his early period. Here are his words from 1935: “Primary forms act on our senses directly. Volumes, light, planes, spaces are the only elements that come into play.” Finally, where the modern movement sought to improve people’s lives through architecture, making it more amenable and comfortable, Miguel López espoused it as a matter of principle.

References

- GARCÍA BRAÑA, Celestino, GÓMEZ AGUSTÍ, Carlos, LANDROVE, Susana, PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, eds., Arquitectura del movimiento moderno en España. Revisión del Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edificios del Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, / Arquitectura do Movimento Moderno em Espanha, Revisão do Regisro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965. Catálogo inicial de edifícios do Plan Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural del Siglo XX, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Arquia, Barcelona, 2019.

- MARTÍNEZ MEDINA, Andrés, OLIVA MEYER, Justo, OLIVER RAMÍREZ, José Luis, “La factoría del Aluminio Ibérico: maquinaria de la metrópoli”, in LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Actas del VII Congreso Internacional Docomomo: La fábrica, paradigma de la modernidad, Fundación Docomomo Ibérico, Barcelona, 2012, pp. 103-108.

- OLIVA MEYER, Justo, MARTÍNEZ MEDINA, Andrés, GUTIÉRREZ MOZO, María Elía, “Memoria gráfica de la Feria Internacional del Calzado (1960-1970)”, in PÉREZ DEL HOYO, Raquel, ed., Apuntes en torno a la arquitectura, Departamento de Expresión Gráfica y Cartografía, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, 2012, pp. 309-341.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos II: Ocio, comercio, transporte y turismo, 1925-1965, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2011.

- LANDROVE, Susana, ed., Equipamientos I: Lugares públicos y nuevos programas, 1925-1965, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2010.

- CENTELLAS, Miguel, JORDÁ, Carmen, LANDROVE, Susana, eds., La vivienda moderna, Registro DOCOMOMO Ibérico, 1925-1965, Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico/Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, Barcelona, 2009.

- JORDÁ SUCH, Carmen, MARTÍNEZ-MEDINA, Andrés, PRIOR LLOMPART, Jaume, Arquitectura Moderna y Contemporánea de la Comunitat Valenciana, 1925-2005, Generalitat Valenciana/Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunitat Valenciana, Valencia, 2009.

- MARTÍNEZ MEDINA, Andrés, OLIVA MEYER, Justo, Dibujos y arquitectura de Miguel López González. 1932-1968, Colegio Territorial de Arquitectos de Alicante, Alicante, 2008.

- JORDÁ SUCH, Carmen, com., Vivienda Moderna en la Comunitat Valenciana, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunitat Valenciana/Conselleria de Medi Ambient, Aigua, Urbanisme i Vivenda, Valencia, 2007.

- COLOMER, Vicente, ALONSO de ARMIÑO, Luis, dirs., Registro Arquitectura del siglo XX en la Comunitat Valenciana, Generalitat Valenciana (2 vols.), Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunitat Valenciana/Universitat Politècnica de València/Instuto Valenciano de la Edificación y Generalitat Valenciana, Valencia, 2002.

- GRANELL I MARCH, Jordi, MARTÍNEZ-MEDINA, Andrés, CORRAL JUAN, Luis, LÓPEZ MARTÍNEZ, José María, VILLANUEVA PLEGUEZUELO, Eusebio, PÉREZ AMARAL, Andrés, dirs. and coords., La arquitectura del sol_Sunland architecture, Barcelona, Colegios de Arquitectos de Catalunya, Comunitat Valenciana, Illes Balears, Murcia, Almería, Granada, Málaga y Canarias, 2002.

- OLIVA MEYER, Justo, “Miguel López González, arquitecto: el ejercicio de la modernidad en la periferia (Alicante 1931-1976)”, in Vía-Arquitectura 9, 2001, pp. 132-137.

- MARTÍNEZ-MEDINA, Andrés, La arquitectura de la ciudad de Alicante: 1923-1943. La aventura de la modernidad, Instituto Cultura Gil Albert/Colegio Territorial de Arquitectos de Alicante, Alicante, 1998.

- VARELA BOTELLA, Santiago, Guía de Arquitectura de Alacant (vol. 2º), Colegio de Arquitectos, Alicante, 1980.

- OLIVA MEYER, Justo, “Turismo y arquitectura: la modernidad por respuesta”, in Vía-Arquitectura 1, 1997.

- MARTÍNEZ MEDINA, Andrés, OLIVA MEYER, Justo, Dibujos y arquitectura de Miguel López González. 1932-1968, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunitat Valenciana, Alicante, 1987.

- GIMÉNEZ GARCÍA, Efigenio, GINER ÁLVAREZ, Jaume, VARELA BOTELLA, Santiago, Sobre la ciudad dibujada de Alicante: del plano geométrico al plan general de 1970, Delegación de Alicante del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de la Comunidad Valenciana, Alicante, 1985.

- VARELA BOTELLA, Santiago, Guía de Arquitectura de Alacant (vol. 2º), Colegio de Arquitectos, Alicante, 1980.

- LÓPEZ GONZÁLEZ, Miguel, “Sanatorio y Casa de Reposo ‘Virgen del Socorro’ en Alicante”, in Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 101, 1950, pp. 219-225.

- MUÑOZ MONASTERIO, Manuel, LÓPEZ GONZÁLEZ, Miguel, “Ordenación y reforma de la Plaza del Dieciocho de Julio”, in Revista Nacional de Arquitectura 43, 1945, pp. 250-253.