The pioneers of the automotive industry in Spain

The pioneering car manufacturers in Spain were concentrated in the Barcelona area: the entrepreneurs in the Catalan textile industry, whether due to personal interest or a business vision, promoted the manufacture of the first prototypes. In 1889, the textile industrialist Francesc Bonet patented and manufactured a “tricycle” for his personal use. It was a carriage in which animal traction had been replaced by a small engine, inspired by the vehicle designed by Göttlieb Daimler, considered the inventor of the automobile. A few years later, now in the 20th century, Damián Mateu and Marc Birkigt founded the Hispano-Suiza company, the first Spanish company to create large-scale serial models that would become famous the world over. At first, their vehicles were more associated with sport and recreation than utility. In the automobile’s infancy, competitions and races were all the rage throughout Spain. Outside cities, there was scant infrastructure suitable for vehicle circulation, and cars were lacking in autonomy, not to mention features associated with safety, comfort or maintenance. Nonetheless, the vehicles manufactured by Hispano-Suiza, very popular with the aristocracy and the monarchy, became symbols of the Belle Époque and modernity. From 1904 to 1946, the company manufactured 12,000 vehicles at its factories in Barcelona, Guadalajara and France.

Ramon Casas, Ramon Casas y Pere Romeu en un automóvil [Ramon Casas and Pere Romeu in an automobile], 1901, MNAC

In the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, Spanish cities witnessed the proliferation of new means of collective transport like the underground (metro) or streetcars. In many cases, these infrastructures determined the forms of cities and their vectors of growth. Yet, the number of private cars was still very limited, and few cities had a network of roads capable of accommodating them. All the same, the progressive increase in the number of vehicles began to demand cities be adapted with new infrastructures to serve them: the first garage buildings appeared at a time when the construction of underground parking was still unthinkable. In Soria, the same businessman who introduced the first vehicles into the city developed a building to be used as a parking garage in the city centre. The Docomomo Ibérico register includes several of these buildings, dating back to before the Civil War, associated with the earliest presence of automobiles in Spanish cities.

One of the most striking is the David building in Barcelona (although it does not correspond to rationalist architecture in stylistic terms). Built in 1931, it is a landmark of Noucentisme inspired by the Chicago School. With a length of 70 meters and located in the heart of the city, its classic and monumental language hides a building that was initially intended as a small-format vehicle factory and later as a garage: all eight floors could be accessed via a cylindrical ramp and internal circulation lanes. Office spaces were eventually added on all the floors, which could be accessed by driving a private car right up to the door, a system that is still in place today.

Edificio David, calle Aribau, Barcelona, Ignasi Mas Morell, 1931.

The first urban service stations also appeared, buildings that aimed to express the modernity of their function through their architecture. In Madrid, we find two futurist-inspired petrol stations designed by Casto Fernández-Shaw – one of them built in 1927 – that have been listed as cultural heritage as characteristic elements of the capital’s urban landscape.

LThe motorisation of the administration and the armed forces

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the burgeoning Spanish automobile industry, and particularly the Hispano-Suiza company, turned toward the manufacture of vehicles for the armed forces and later vans, trucks and especially diesel engines for land, sea and air vehicles.

The incorporation of motorised vehicles was key in the course of the war in Spain, and it served to test new models and technology that would later be used in the World War that was looming. The purchase of trucks and battleships was one of the great logistical battles between the two sides: Italian FIATs and German Panzers on the Nationalist side, and French Renaults and Soviet T-26s and BT-5s among the Republicans. The result was the total motorisation of the two warring armies. The importance of motor vehicles for the armed forces led to the creation of a School for Drivers and Specialised Workers, which opened in Madrid just after the Civil War. After the war, the public administration was also motorised, and the first fleets of vehicles for civil use were created.

“Since our Homeland lacks the mechanical culture that exists in other countries and which serves to support the mission of driving and maintaining the thousands of Army vehicles, we need ongoing education and technical training for drivers and mechanics. The low density of motorisation in civilian life, together with the youth of the recruits, which makes it impossible for them to have received trained in their trades before arriving at the barracks, are factors that make it necessary to intensify training within the ranks, to make up for the deficiency in quantity and quality. This educational effort ultimately benefits civil society, which receives an influx of knowledgeable men who, little by little, will provide the wealth of mechanical expertise that Spain so desperately needs.” Arias Paz, Manuel, Un aspecto de la educación militar, la escuela de automovilismo del ejército, Revista Nacional de Educación, Madrid, 1941.

Just after the Civil War, there was a dramatic increase in passenger transport by road, which made use of cheaper infrastructure than railway transport. The famous omnibuses began as passenger cars pulled by horses or mules, and their natural evolution was towards electrification or the incorporation of combustion engines (an option that provided total freedom of movement and which ended up prevailing). Barcelona introduced its network of buses in October 1922, which eventually replaced the extensive system of streetcars. After the Civil War, regular bus lines were introduced beyond the city limits in long routes crossing the province and even the country. These bus lines supported the exodus from the countryside to the city, and many of the people who were displaced during the great waves of internal migration in the 1960s travelled on long, one-way bus trips.

Consequently, bus stations became central elements of great importance in many Spanish provincial capitals, resulting in magnificent examples of buildings whose association with transport justified architectural languages rooted in modernity and with ties to rationalism.

In 1959, the growing motorisation of the country justified the creation of the General Directorate of Traffic, a body dependent on the then Ministry of Governance, now Ministry of the Interior. It was created with the aim of combining powers that had previously been scattered across other departments of the administration and attending to the expansion in the circulation of motor vehicles that was taking place in Spain.

SEAT: the Spanish automobile company

After the war, the drop in profits at Hispano-Suiza led to its progressive nationalisation between 1944 and 1946. The public company ENASA was created, which eventually became the Sociedad Española de Automóviles de Turismo, SA (SEAT) in 1950. In 1949, the Francoist regime had commissioned the National Institute of Industry (INI) to create a state-owned automobile company with the aim of motorising post-war Spain through the manufacture of Italian FIAT cars under a licensing agreement. The INI was the majority shareholder, the Spanish Bank was the second shareholder, and the Italian company FIAT held a 7% participation.

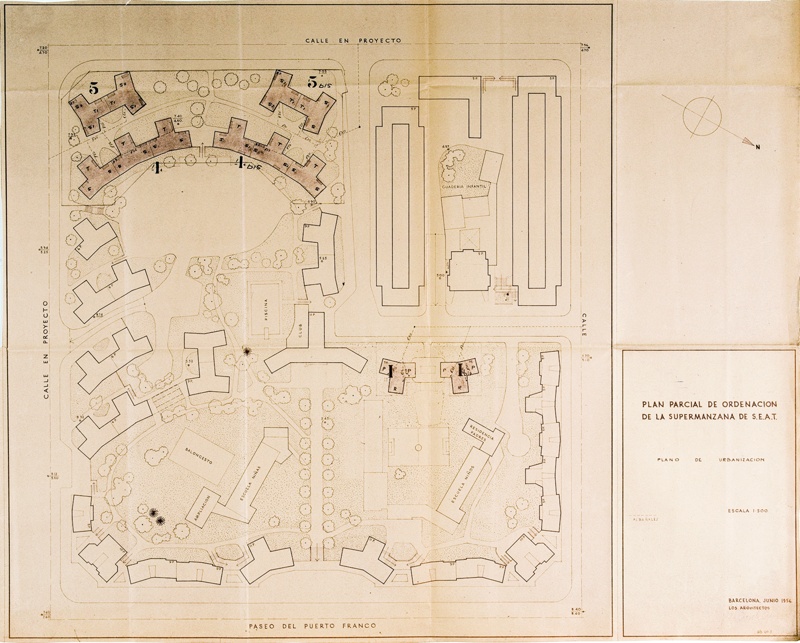

SEAT began its industrial activity in Barcelona’s Zona Franca. The option of the Bilbao estuary had been considered for the location of the main factory, but the Catalan engineer, architect and businessman, José María Bosch Aymerich, who had considerable influence in the INI (he was technical director of the Zona Franca), seems to have been responsible for the option of Barcelona winning out in the end. Over the years, Bosch Aymerich would be one of the architects who played a prominent role in the major works required for the expansion of the company, specifically in the construction of a housing district on Passeig de la Zona Franca in Barcelona, with its corresponding services and facilities, intended for the company’s workers.

Partial Plan for the SEAT Superblock in the Zona Franca. Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich, Antoni Pineda i Gualba. Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich Collection, COAC Historic Archive.

Type plant of a housing block by Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich in the supersquare of SEAT, in the Zona Franca (Barcelona). Cuadernos de Arquitectura 14, 1953, COAC Historic Archive.

Production began in May 1953 with the SEAT 1400, a direct derivative of the Fiat 1400 from 1950. The popular SEAT 600 did not arrive until June 1957, at a price of 65,000 pesetas, which fell in subsequent years.

The first chairman of the company was the military engineer José Ortiz Echagüe, who, from the outset, placed special importance on avant-garde design as part of the company’s brand identity, not only in the design of the vehicles but also in the architecture. As part of the development and expansion of the production complex, which was at a high point thanks to the popularity of the 600 model, a series of canteens were built for the company’s employees. José Ortiz Echagüe gave the commission to his son, César Ortiz-Echagüe Rubió, who had just been certified as an architect in Madrid.

The building he proposed, in collaboration with two other designers (Manuel Barbero Rebolledo and Rafael de la Joya Castro), offers an atmosphere of peace, on a human scale, contrasting with the massive size and frenetic activity of the factory itself. Its resounding modernity was no doubt inspired by buildings published in the first international architecture magazines that were beginning to arrive in Spain, rather than the atmosphere the architect had been exposed to at the Madrid School of Architecture at the end of the 1940s. The building’s construction is nearly entirely mortarless, with industrialised elements on its façade and an innovative load-bearing aluminium structure, using technology inspired by aeronautical construction. After its construction, the designers submitted the project for consideration for the Reynolds Prize, organised by the American Institute of Architects, which recognised the use of aluminium as a construction material. The jury, whose members included Mies van der Rohe and W. M. Dudok, among others, awarded the prize to the building by the young Spanish architects, which served as a milestone in their career and was one of the first international awards for Spanish modern architecture. Also worth noting is the attention the authors gave to the design of the exterior spaces, pergolas and gardens that contrast geometrically with the rigorous, serial architecture of the pavilions intended for dining rooms and kitchens.

The trio of architects who designed the dining rooms maintained a close connection with the company, for which they designed a series of buildings in the 1950s, both as a team and individually.

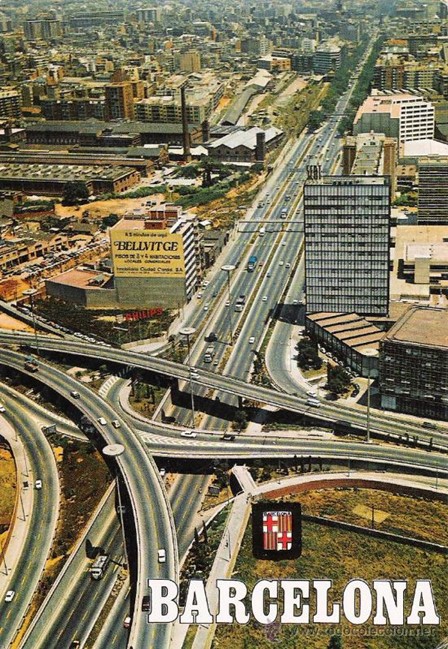

Notable among them is the office complex, quite disfigured at present, on what is now Plaça Cerdà. It was a tall office building and a six-storey garage-exhibition space, connected by a low-rise volume. The three volumes were designed with a curtain wall and were clearly influenced by the American architecture of Mies van der Rohe. The vehicles exhibited inside the large glass box, brightly lit at night, suggested an association between their modernity and a ground-breaking, spectacular kind of architecture. The building, on the main road leading into Barcelona from the city’s airport, was intended as an advertisement, a reflection of the image of industrial strength and modernity that Barcelona hoped to project during the 1960s.

Postal de Barcelona postcard showing the western access to the city, with the Gran Via as the main road and Cerdà Square in the foreground. On the right, the office buildings and the showroom, by César Ortiz-Echagüe Rubió, Manuel Barbero Rebolledo and Rafael de la Joya Castro.

The Seat 60o model

The creation of a national automobile industry responded to a clear need: there were hardly any private vehicles in the national territory. The sum total of cars, motorcycles, trucks, and tractors barely reached 100,000, and most of them belonged to public institutions, passenger transport companies, or the Army.

This foundational purpose behind the SEAT company would be fulfilled in 1957 with the introduction of the SEAT 600 model, its most emblematic vehicle. The 600 is the iconic, quintessential element representing the incipient industrial and social development in post-war Spain, and it was the first car ever purchased for hundreds of thousands of Spanish citizens. A total of 795,000 units were manufactured and sold at a very affordable price, which was maintained or reduced over the years despite the technical innovations incorporated into the different models. For the Franco Regime it represented an excellent focal point for propaganda: the working class could finally have access to a car and a home of their own (thanks to an ambitious programme to build public housing estates). Through the use of propaganda – in films, television and advertising – a car and a house became seen as elements of tangible material progress and symbols of development and modernity, proof that the hardships of the post-war period were finally in the past.

The popularisation of the 600 model demanded the creation of SEAT subsidiaries in multiple Spanish cities and the opening of new factories. The subsidiaries were not exactly factories, but marketing and distribution points housing a variety of programmes: showrooms, new vehicle warehouses, workshops, offices, etc. Due to their strategic location in large capital cities and in highly visible places, they acted as the precursor to today’s car dealerships, which are so characteristic of the urban landscape on the outskirts of many Spanish cities.

A country on wheels

The popularisation of the private vehicle, through the SEAT 600, brought about a veritable revolution. In the first place, the urban spaces of the vast majority of Spanish cities were not prepared for large-scale traffic, nor did they have spaces for the storage of vehicles. Consequently, cities needed to be quickly redesigned or adapted to accommodate cars, both in public space and in the private sphere. This took place rapidly and often without planning, which had a serious impact on the urban landscape of city centres. In the medium term, because cars were a symbol of progress and modernity, the redesign of cities to suit them was also a symbol of forming part of the avant-garde and was seen as something desirable. In Barcelona, the push for development wholeheartedly embraced car culture in urban design: road junctions entered into the imaginary as associated with cities, not just motorways. The problems derived from congestion, the colonisation of public space by private vehicles and the loss of environmental quality – due to combustion engines – are still among the main challenges facing urban planning today. Patterns of urban growth were also strongly affected: the capacity for individual mobility served as justification for disconnected pockets of urban growth, in discontinuous and more remote spaces, feeding phenomena such as “bedroom communities” and suburban industrial estates or shopping centres that are only accessible by car.

The entire country had to adapt to the invasion of vehicles with new infrastructures that changed the territory. Highways and national and provincial roads offered a new way of understanding the territory, and new landscapes were born around them that included repair shops, petrol stations, motels, service areas and roadside restaurants.

The total freedom of movement for families, the improvement of working conditions and workers’ rights, and the new infrastructures made it possible for people to set out toward the coasts and natural landscapes on weekends and for their holidays. Parallel to the arrival of foreign tourism, local Sunday drivers discovered the beaches, reservoirs and mountains, forever changing the collective idea of leisure and rest and thoroughly modifying the landscape through campsites, hotels, holiday homes and tourism infrastructures. A holiday home by the beach became another of the aspirations of the late Francoist Spanish working class.

Unions, large corporations and public companies, encouraged by the regime, built vacation complexes for workers and their families. These small seasonal cities, mostly on the coast, were comprised of dozens of bungalows or simple small constructions, along with restaurants and sports and leisure facilities. These complexes offered the possibility of experimenting with new small-format architecture and layouts that were more in harmony with the landscape, which led to the recovery of ideas and models that dated back to before the Civil War, like the “Ciutat de Repòs i Vacances” designed by the GATPAC on the coast south of Barcelona.

Ciutat de repós i vacances [City of Rest and Holidays], GATPAC, COAC Historical Archive..

Bibliography and references

Arias Paz, Manuel,”Un aspecto de la educación militar, la escuela de automovilismo del ejército”, in Revista Nacional de Educación, Madrid, 1941.

López Carrillo, José María, “Los orígenes de la industria de la automoción en España y la intervención del INI a través de ENASA”, Documento de Trabajo 9608, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Departamento de Historia Contemporánea, Fundación Empresa Pública, Madrid, november 1996.

CARCELÉN GONZALEZ, Ricardo, “Cuando la clase obrera se hizo turista”, Pasos, revista de turismo y patrimonio cultural, vol. 17 num. 5, Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, Cartagena, 2019.

Museo SEAT: Génesis del Seat 600. Diseño, gestación y desarrollo Estructura y características básicas.

RTEV PLAY RADIO (online repository), El SEAT 600, la España de las cuatro velocidades, 2013.

SAUQUET LLONCH, Roger, Carlos (dir), La ciutat de repòs i vacances del Gatcpac (1931-1938). Un paisatge pel descans, Phd Thesis, Universitat Politècninca de Catalunya, UPC, Barcelona, 2012.

OCHOTORENA ELÍZEGUI, Juan Miguel dir., POZO MURICIO, José Manuel, coord., AACC 02 | Comedores de la SEAT, Arquitecturas Contemporáneas, T6 Ediciones, Pamplona, 1999.