The Origins of Mass Tourism on the Coast of Málaga

One of the original hotspots of industrialization in Spain was the coast of Málaga, sustained by the blast furnaces built by the Heredia family in the cities of Marbella and Málaga in the early 19th century. The subsequent decline of the industry led to a serious crisis in the local economy, compounded by thegrape phylloxera plague that affected the winemaking business and sparked the need to seek new sources of wealth. In response, the Society for the Promotion of the Climate and Beatification of Málaga was formed in 1897, which included prominent members of civil society. The stated purpose was the promotion of tourism, which, at the time, was a minority activity and enjoyed by only the most well-to-do sectors of society. Curiously enough, the city’s benefits were meant to be exploited in the winter season as opposed to the summer, due to the mild temperatures in the coldest months of the year.

The first establishments intended for this new tourist activity were tied to existing urban centres. Their bourgeois architecture blended normally into the city’s streets and was not much different from that of similar hotels in other places, except for the subtropical characteristics and the exotic flora in their gardens, as well as their location near the beach. The most significant example at the local level is the current Hotel Miramar, initially called the Hotel Príncipe de Asturias. Located on Malagueta Beach, it was built in 1926 according to a design by the architect Fernando Guerrero Strachan.

Hotel Príncipe de Asturias (now Hotel Miramar), c. 1928. Source: L. Roisin, IEFC Historical Photographic Archive (Barcelona)

The origin of mass tourism along the coast of Málaga can be pinpointed to 1953, coinciding with the signing of the Pact of Madrid. The document marked the Franco regime’s opening to the exterior and kicked off the economic development of Spain, in which the phenomenon of tourism played a fundamental role. The Ministry of Information and Tourism was created in 1951; up to that point, the General Directorate of Tourism had been the body responsible for those functions. In Málaga, a Board of Trustees was created to handle development in the area called the Costa del Sol, the boundaries of which initially extended along the coastline into neighbouring provinces. The presence of an international airport provided the necessary momentum. In a novel way, the urban growth was disconnected from the existing settlements, and the larger area as a whole became the focus for the planning of the developments.

Camping Marbella, km. 191 of the N-340. Source: Archive of the newspaper La Opinión de Málaga

The N-340 as the Connector

The orography of the coast of Málaga is characterized by its mountains, which are located very close to the sea, leaving a narrow strip along most of the coastline with very few and difficult connections to the interior. The area is structured linearly along the old N-340 national highway, which ties together the different towns located along the shore. The towns of Torremolinos, Benalmádena, Fuengirola, Marbella and Estepona sit along the coast to the west of the city of Málaga. Initially, and until the respective bypass roads were built, the national highway served as a kind of “main street” that crossed the historic town centres and concentrated the urban activity. The new urban developments associated with tourism inevitably continued this type of occupation, lining up along the road, which became the virtual boundary between the beach and the mountains, as well as the only mode of communication. From that point forward, the N-340 began to be dotted by developments all along its edges, laying the foundations for what has sometimes been described as a linear city, ultimately resulting in an urbanized continuum of some 80 km in length.

Until the late 1960s, the first tourist developments followed the garden city pattern, and their predominant typology was that of the single-family home. In stylistic terms, the architecture took on the typical features of the Andalusian vernacular, and the designs were mostly carried out by local architects. However, there was soon a significant leap in scale, fuelled by a large influx of foreign capital – a product of the opening of the regime and the take-off of the economy. This resulted in numerous designs drafted by prestigious architects, many of whom came from outside Málaga and were prominent on the national scene, who had embraced the postulates of the Modern Movement.

The precise moment of this paradigm shift can be dated to the construction of the Hotel Pez Espada in Torremolinos, designed by the architects Juan Jáuregui Briales and Manuel Muñoz Monasterio in 1959. Without the constraints imposed by an existing urban layout, and serving a recreational programme aimed at tourists engaging in leisure activities of a markedly seasonal nature, the architecture that began to emerge took its only references from orientation, climate, and the untouched natural settings that offered enormous landscape and environmental values at the time.

Hotel Costa del Sol, Torremolinos, 1959. Source: Estudio Fotográfico Arenas, Historical Archive of the University of Málaga

The Dogma of Sun and Sea

By contrast, the predominant typology from that point forward became the hotel and, later, the apartment block. These were free-standing buildings, stacked vertically to free up the area around them for gardens and swimming pools, and they were built on virgin land. The only connection between these towers and the urban centres was the N-340.

Hotel Carihuela Palace under construction, Torremolinos, 1959. In the background, the silhouette of the Hotel Pez Espada can be seen rising above the Montemar holiday district, which follows the garden city typology. Source: Estudio Fotográfico Arenas, Historical Archive of the University of Málaga

The novel Torremolinos Gran Hotel – published in 1971 – referred to the Hotel Pez Espada, perfectly recognizable in the text, as a “gigantic ocean liner with its prow on the beach”. The description precisely defines a type of implementation in the territory that served as the foundation for a model that would spread and proliferate for years. With the well-intentioned criterion of avoiding obstructing views of the Mediterranean from the buildings in the second row, the building ordinances dictated that built volumes must be oriented perpendicular to the coast. The units were distributed across numerous rectangular floors that were repeated vertically, organized along a corridor that served as a connector, and facing outward to provide sea views and the best orientation. Sometimes, the angle of the balconies was rotated with respect to the main axis of the building’s floor plan to generate a sawtooth profile, in order to get the best out of both the orientation and the views. This is the case of the Pez Espada, for example, where the main vertical communications core, as well as the entrance and reception, are situated on the least desirable façade – to the north – facing the N-340.

Hotel Pez Espada, Torremolinos, 1963. In the background, several blocks from the Eurosol complex can be seen in various phases of construction. Source: Estudio Fotográfico Arenas, Historical Archive of the University of Malaga

Subsequently, other more complex floor plans were tested out once the regulations requiring a strictly perpendicular arrangement with respect to the sea were no longer in force. The consequence was the creation of a line of buildings along the oceanfront, but also the appearance of typologies with Y-shaped floorplans or in the form of boomerangs, as is the case of the Hotel Don Pepe in Marbella, a design by Eleuterio Población Knappe from 1961. Of particular interest in this respect is the Hotel Tres Carabelas, designed by the architect Antonio Lamela in that same year – and expanded in 1975 – which reconciles optimal orientation with the unfavourable geometry of the site.

On the other hand, the nature of summer leisure in southern climates encourages outdoor activities, not only on the beach and in the gardens but also in the rooms themselves, where the terraces are seen as a natural extension of the interior, resulting in an unusually large ratio between exterior and interior in each unit. Facing south and west, cantilevers and lattices are recurring elements for protection against sun exposure. When the intense summer sun hits these volumes, which are repeated across the entire envelope of the building, the stark shadows they project onto the façade generate a highly plastic effect, a result that is particularly effective in floorplans with a serrated profile.

Hotel Tres Carabelas, Torremolinos, 1961. The complex was demolished in January 2007, when it was called the Hotel Meliá Torremolinos. Source: Estudio Lamela

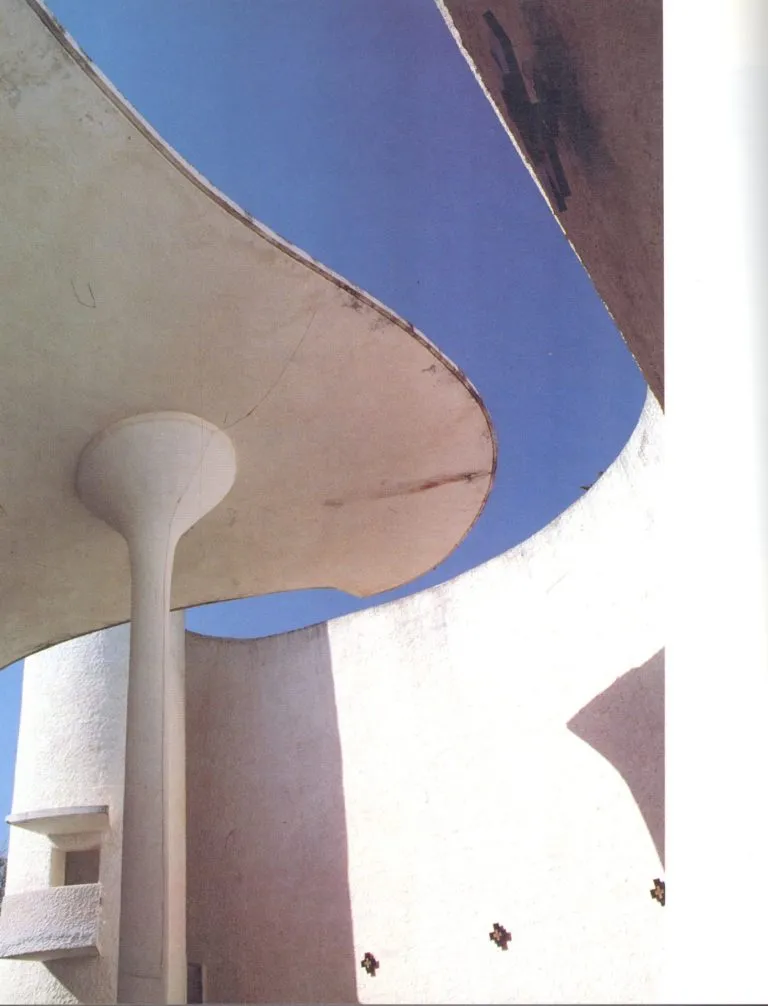

The interior floors are reserved for the services in complexes that are intended to be self-sufficient, thus avoiding the need for guests to leave for the entirety of their stay. With a height limited by the aforementioned easement of views, the volumes dedicated to services extend horizontally at the foot of the towers in long adjacent modules. They act as a base while housing the lobbies, lounges, and shopping areas, among other uses. This results in open unobstructed spaces, where the structure of the tower can take on an imposing presence. Sometimes, this provides the occasion – as in the Hotel Don Carlos in Marbella, the work of the architects José María Santos Rein and Alberto López Palanco – for adopting striking solutions for the design of the supports, with impressive sculptural forms. In other cases, suggestive surface treatments are used, like the amoeba-shaped columns in the entrance hall of the Hotel Pez Espada. When the topography allows it, underground levels can be used to reduce the visual impact of the buildings, a solution made possible by the position of the N-340 with respect to sea level, as seen in the Hotel Alay in Benalmádena, designed by the architect Manuel Jaén Albaitero in 1962.

Also noteworthy are the various technological innovations, hitherto unheard of in Spain, that were implemented in some of the hotels along the Costa del Sol, such as the introduction of entire storeys dedicated to plant rooms or the centralization of services on standard floors. The Hotel Tres Carabelas in Torremolinos was pioneering in that respect.

Entryway to the El Remo building, Torremolinos. Source: Photograph by the author

“Relax Style”

Beyond the volumetric forms described above, the leisure-oriented architecture on the Costa del Sol is set apart by a particularly liberal use of functional and decorative features. Numerous elements, including tile, murals, signs, furniture and wrought iron pieces are integrated as parts of a whole. This characteristic resulted, initially, from a lack of modernization in the construction processes, which relied on artisanal solutions and the architect’s own creativity – with remarkable outcomes in many cases. The phenomenon was dubbed “relax style”, an appropriate name that was seen for the first time in a book with the same title published by the Architects’ Association of Malaga in 1987. By then, the excesses in development had already resulted in a considerable deterioration of the area’s landscape heritage, and the book suggested the interest of documenting the “archaeology of leisure” in catalogue form, since the architectural heritage was also coming under threat at the time, and there was no legal instrument to ensure its protection.

The cultural phenomena that emerged surrounding this architecture is also relevant. It had repercussions, for example, in the visual arts, particularly in the new figurative painting from Malaga in the 1980s. Worth citing is the work of Guillermo Pérez Villalta, who did several paintings of the hotel architecture on the coast. One example is Personaje indeterminado frente al Pez Espada [Unidentified Figure in Front of the Hotel Pez Espada], from 1975, or his various versions of the Carihuela Palace hotel.

Views of Bajondillo Beach. Playamar Towers. Torremolinos, 1973. Source: Estudio Fotográfico Arenas, Municipal Archive of Málaga

The Difficult Conservation of a Valuable Legacy

The progressive urbanization of the Costa del Sol ended up filling in the increasingly small unbuilt interstitial spaces remaining between complexes that were designed, in their day, as independent islets. The result was an unbalanced puzzle, in which the different pieces were impossible to fit together. However, the oil crisis of 1973 put an end to the process as described here, in what Joaquín Aramburu called, “The first invasion of large rectangular towers [that] extended up to the shoreline.” This global crisis made international travel much more expensive and triggered a sharp decline in demand in the tourism industry. With the passage of time, the crisis abated and a new sensibility arose that demanded different, more extensive models of occupying the territory, which were seen as less harmful in their occupation of the landscape and the territory, but which, ultimately, consumed more surface area. The architecture was neo-vernacular in its appearance, although the inspiration remained more cosmetic than real, and stood in sharp contrast to the language inherited from the Modern Movement that characterized the buildings from the period immediately before.

In the same way, coinciding with this change in sensitivity, there was a growing awareness of the problems caused by the absence of effective protection for this valuable architectural legacy. The threat that the authors of Relax Style had intuited ended up coming to a head in the form of serious heritage losses; the high point came in 2008 with the demolition of the old Hotel Tres Carabelas. It was meant to be replaced by a much larger hotel, which did not get built in the end. In a more silent but equally damaging way, a misunderstood desire for renovation has chipped away at the material quality of many of the hotels, with the removal of original elements from their interiors, as well as finishes and ornamentation. A good example of this was the attempted destruction of the entryway to the apartment building located at paseo Marítimo 31 in Málaga, and the movement that emerged in protest offers some hope in this regard.

The building, the work of the architect Antonio Lamela from 1971, had maintained the original decoration of its common areas, which the management board intended to renovate without any regard for the original design. The protests that emerged in response, with the support of the Architects’ Association, ultimately managed to stop the planned intervention. The event had a significant impact in the media and led to the declaration of the building as cultural heritage by the regional administration, which resulted in a greater awareness among the general population regarding the heritage of the Modern Movement.

Bibliography

- ARAMBURU, Joaquín, “Perplejidad y consternación en la arquitectura”, in A&V monografías 4, Andalucía: El Sur, Madrid, 1985, pp. 12-15.

- ARCAS CUBERO, Fernando, GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ, Antonio, “Los orígenes del turismo malagueño: la Sociedad propagandista del clima y embellecimiento de Málaga”, en Jábega 32, Centro de ediciones de la Diputación de Málaga, 1980, pp. 42-50.

- BONILLA, Juan, La Costa del Sol en la hora pop, Fundación José Manuel Lara, Sevilla, 2008.

- LOREN MÉNDEZ, Mar, “La arquitectura de la Costa del Sol y la relatividad del pecado especulativo de los sesenta. De la censura y el pudor a la protección”, in Revista de historia y teoría de la arquitectura 8, Universidad de Sevilla, 2006, pp. 29-46.

- MESALLES, Félix y SUMOY, Lluc, coords., La arquitectura del sol, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Col.legi Oficial d’Arquitectes de les Illes Balears, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Murcia, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Almería y Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Málaga, Barcelona, 2002.

- MORALES FOLGUERA, José Miguel, La arquitectura del ocio en la Costa del Sol, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, 1982.

- PALOMINO, Ángel, Torremolinos Gran Hotel, Alfaguara, Madrid-Barcelona, 1971.

- PÉREZ ESCOLANO, Víctor, PÉREZ CANO, María Teresa, MOSQUERA ADELL, Eduardo, MORENO PÉREZ, José Ramón, 50 años de arquitectura en Andalucía. 1936-1986, Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes, Junta de Andalucía, Sevilla, 1986.

- RAMÍREZ, Juan Antonio, El estilo del relax. N-340. Málaga, h. 1953-1965, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Málaga, Málaga, 1987.