In recent years, research and architectural innovation has once again turned towards social and collective housing. Following decades of a prevalence of private development in Spain, the construction of public housing has been reactivated, which has encouraged research in these areas. Moreover, as a consequence of the crises and tensions that have affected housing in our country, research has delved into aspects that extend beyond typological innovation to address issues related to ownership and models of cohabitation. As a result, in recent years, forms and formulas of living ─ what has been called “cohousing” ─ have been tried out in Spain, in which the concepts of community and cohabitation have been translated into new programmes and formal solutions associated with collective housing, proposing residential options that offer alternatives to traditional housing models. Similar experiments have had a long history in other European countries – since the early 20th century and continuing into the present – but in Spain, they were not always developed in consonance with social needs and demands.

Given this context, it is worth revisiting the 20th-century research that has contributed solutions to house the broad spectrum of experiences that can fall into the category of community living.

In the broadest terms, the aim is to reflect on the boundary line that separates common areas from private areas and, in the domestic sphere, the different gradients of privacy that define the physical and functional relationships between private rooms and shared spaces, between common spaces and the street, between the street and the city, etc. In other words, the goal is to analyse residential models, both in spatial terms and in terms of the provision of services, the relationship between private, shared and public spaces, and how all this transcends the idea of the traditional family unit as the only valid foundation for designing residential buildings.

Cohousing in transfer of use. La Borda. Coop, Lacol, 2018

Source: Barcelona Municipal Institute of Housing and Renovation

To understand the variety of possibilities offered by residential associations, collective housing must consider models of cohabitation that are not based on the repetition of a module intended for a traditional family: for example, religious communities, temporary housing (students, researchers, etc.), or alternative social models. In short, the goal is to understand how different architectural models have offered spatial solutions that can help create different social interactions and that transcend the canonical relationship between private rooms, dwellings, shared spaces, and public spaces.

History is full of experiments and examples of building models that have contributed diverse models for community life. From an architectural point of view, there are four typologies that encompass a majority of these models:

- The agricultural villa (suburban palace) and the productive colony: communities based on production – first agricultural and then industrial.

- The commune and its translation into various models of multi-family grouping, from a building to a residential neighbourhood with shared services – and many examples where the aim is to break down the barrier between neighbourhoods and buildings, between living spaces and the city.

- Religious communities.

- Temporary accommodations or halls of residence, including sanatoriums, boarding schools and accommodation for university students, which extends into typologies associated with tourism: hostels, hotels, spas, etc.

Translated into the architecture of the modern movement, convents, schools, university halls of residence, and investigations of new models of collective housing provide countless examples of alternative living communities.

Productive Communities

Since ancient times, the size of groups of humans living together in societies depended on their ability to supply themselves, first of all, with enough food. Agriculture and livestock anchored communities to a place; technological improvements and surplus became the basis for growth and an increase in organizational complexity, eventually leading to the foundation of the first cities. That said, small human groups dedicated to the exploitation of a small territory ─ enough to be self-sufficient and generate a minimum surplus, if any ─ offered the format for how the territory was organized historically. The need to provide security for this system, which in turn makes cities possible, gave rise to political systems such as feudalism and social classes based on land ownership.

In many cases, the model of community living was characterized by a strict hierarchical organization, where work – whether agricultural or industrial – constituted the cohesive element in the inhabitants’ lives. Since the era of Romanization, self-sufficient agricultural villages provided a model for territorial occupation that spread widely through Mediterranean countries, where it still persists today in the form of farmhouses and country properties scattered throughout the rural territory. During the Renaissance, this model of suburban life was elevated as a lifestyle associated with the nobility: Renaissance villas reflected this refinement with the addition of sophisticated gardens. Villas, palaces and châteaux associated with farms and agricultural production organized the landscape of many Western countries, where there was still a largely rural population and a social structure based on the ancien régime, with the nobility and the church at the top of the social structure maintaining ownership of the land. Although their principles were not strictly linked to working the land, the large suburban palaces built by absolutist monarchs offer great examples of community living that was enormously hierarchical and complex. The Palace of Versailles is the prime example and the height of sophistication in this regard, since it housed the entirety of the French nobility in a centralized way, along with all the nation’s power and decision-making structures. The aim was a disengagement of the nobility from their agricultural properties in pursuit of greater control for the monarch.

During the 20th century, the progressive abandonment of the rural world, driven by industrialization and changes in social organization, led to the decline of agricultural homesteads. In their place, new communities appeared associated with new forms of production and the exploitation of resources. In the second half of the 19th century, industrial colonies needed to be built in places with direct access to water; thus, many were set up in newly built communities and suburban spaces. Similarly, the mining towns on the Cantabrian coast and in Andalusia constituted new forms of social grouping derived from the construction of workers’ accommodations adjacent to production sites. These communities, built ex novo, had to provide not only accommodation but all the necessary associated services because of their isolation. In some cases, this isolation translated into a strict control of all aspects of the workers’ lives on the part of the employer and the company.

Image of the mining town of Fontao in poblado minero de Fontao in 1954

Source: Fontao Mining Museum

In the late 20th century, new communities associated with labour were created in the form of towns intended to compensate for the residents’ isolation with quality community services for employees and their families. The new towns built by the Franco regime throughout Spain are a good example of socially homogeneous communities, in which a series of shared services are provided. They were built to resemble rural towns, in keeping with a larger, comprehensive project. The church, town hall, shops and civic centre always occupy the heart of the settlement, which is laid out like a town square and serves as the setting for the community’s social life.(See the exhibition “New Towns under the Franco Regime”).

Later, the towns associated with nuclear power plants, like Hifrensa, built for the workers at the Vandellòs nuclear power plant, concentrated inhabitants in closed communities with abundant services and facilities for the workers and their families.

Communes: Research and Utopia in Collective Housing (1960-1970)

A commune, according to the dictionary, is not defined as a place, but as a group of people living in an economic, and occasionally sexual, community, outside the bounds of organized society. Communes are closed off, independent communities of people who constitute a group that is ideally self-sufficient, with its own code of conduct and relationships and with limited contact with the outside world – in other words, with society at large.

The internal organization of these communities – which hark back to “tribes” and the first human collectives – can vary, although they are often characterized by not recognizing family as the basic social unit. Throughout the 20th century, communes saw an important evolution supported by new political systems, and they were especially characteristic of communist regimes (communist kommunalka, or communal apartments). That said, populist and fascist regimes also advocated prioritizing the collective over family. Following the Second World War, these communities emerged as a form of protest and as a project that ran counter to traditional social organizations, like in the case of hippie communes or pseudo-religious communities under the leadership of a guide or guru.

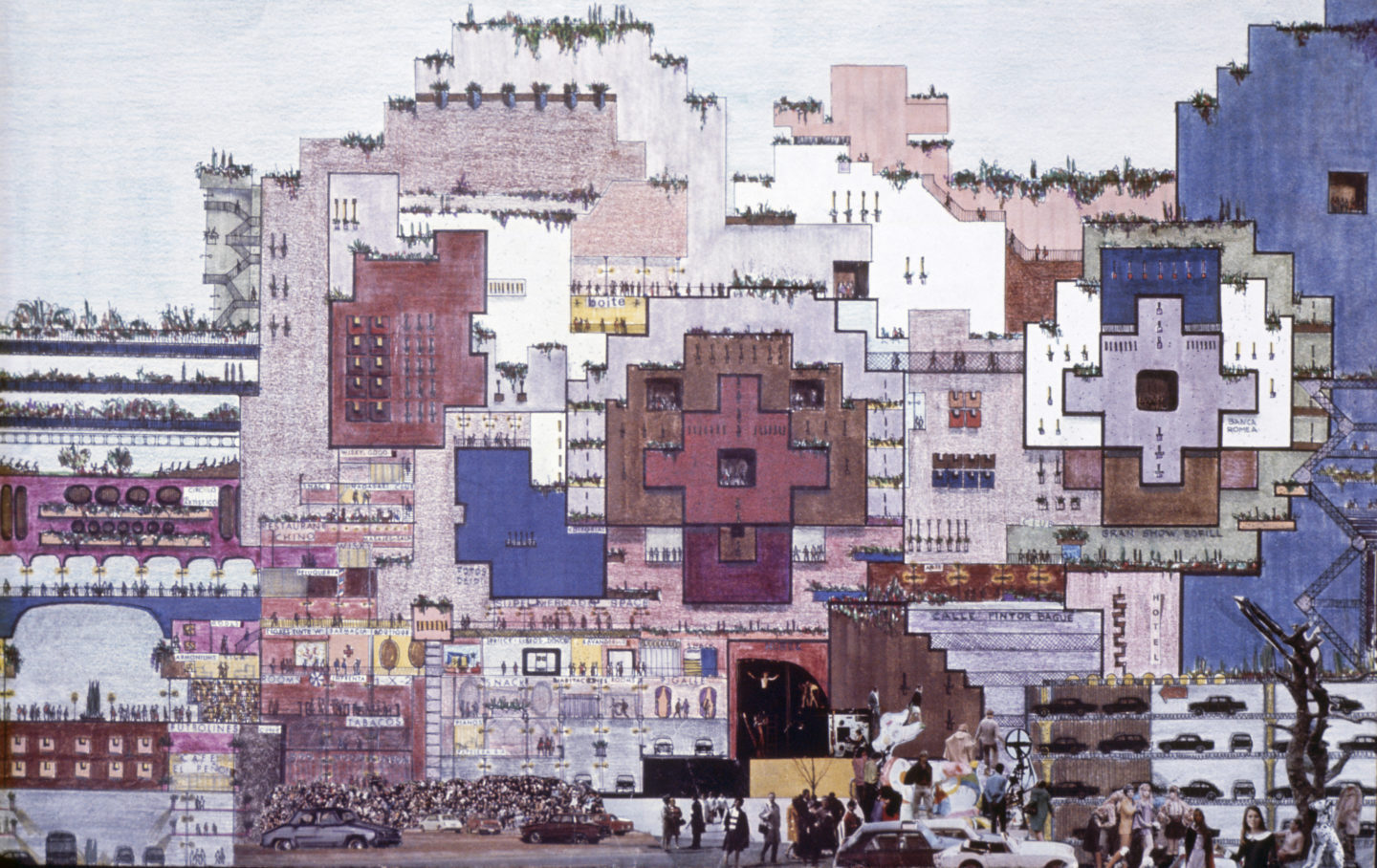

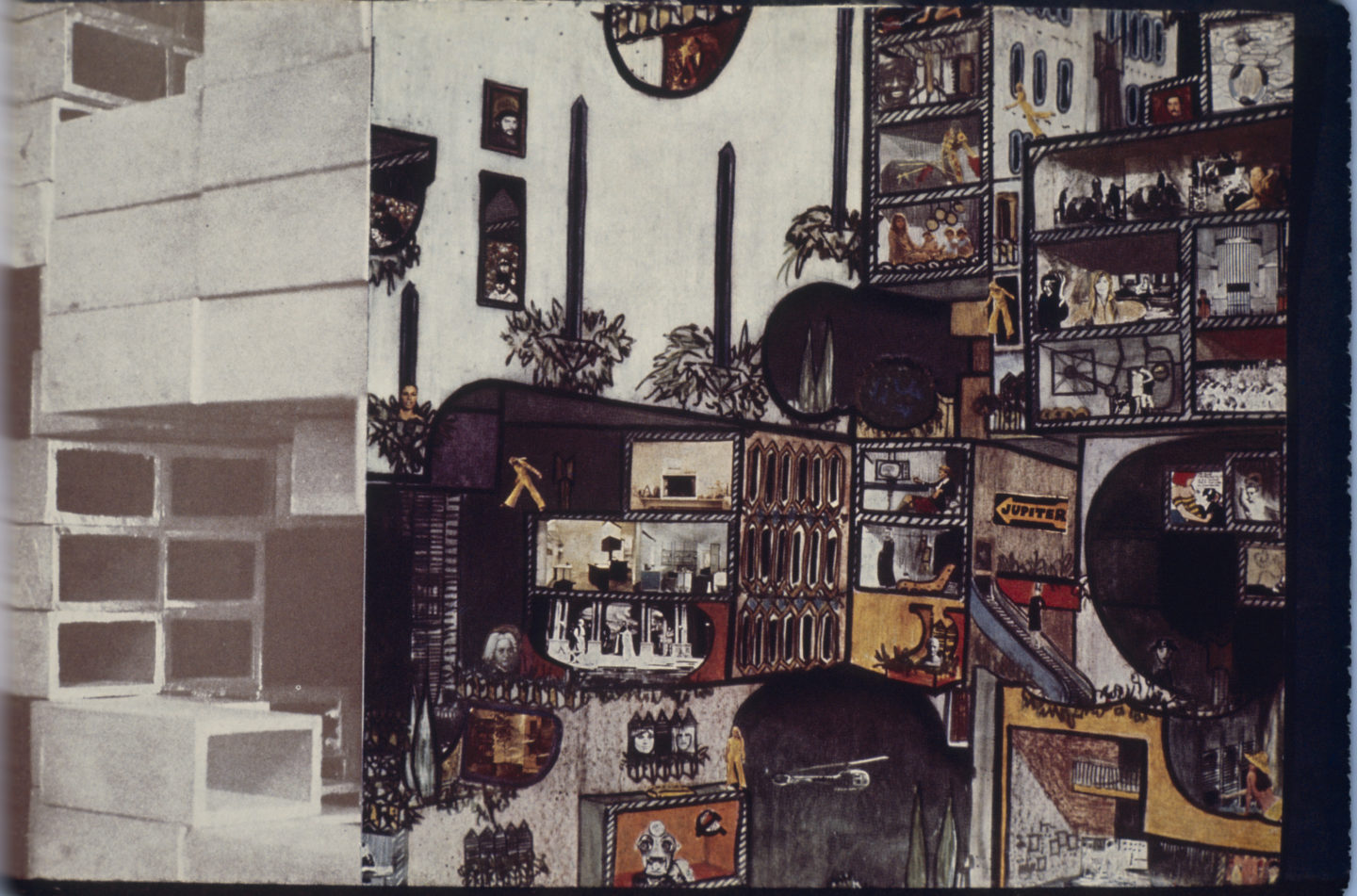

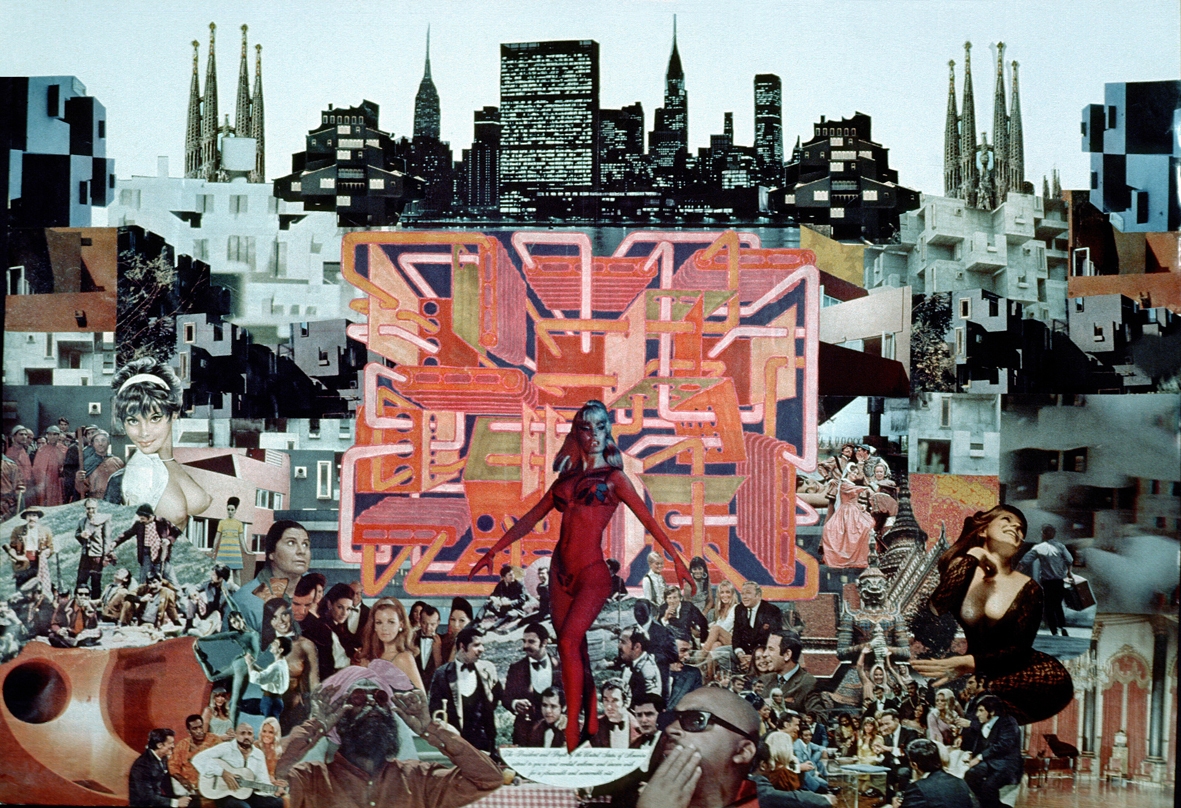

Certain multi-family architectures took a “romanticized” view of the commune as synonymous with a rejection of bourgeois social stereotypes. In the social and philosophical framework of the 1960s and 1970s, idealism and utopia permeated architecture that believed it was possible to advance towards a freer society through the creation of new architectural and urban forms. This translated into new forms of spatial groupings and typologies backed by a large amount of research. In Spain, the Taller de Arquitectura led by the Bofill brothers brought together professionals from various disciplines to develop their “City in Space”, a self-managed community where the different functions were spread across a three-dimensional structure that was elevated off the ground in a clear reference to Constant’s New Babylon project. Their research culminated in real achievements that represented a revolution in collective housing buildings, including Kafka’s Castle and Walden 7. Likewise, in Barcelona, the Fullà House by Studio PER is emblematic of a generation that, at the end of the 1970s, sought unconventional lifestyles rooted in counterculture, in which community was given more importance than the conventional family from the Christian tradition. As a result, the building was referred to as the hippie house, and its inhabitants included figures like Joan Brossa. Although the idea for the project drew on a political ideology that made reference to the concept of the commune, it does not contemplate the dissolution of the concept of private property or private space. Unique buildings were also built in Madrid, like the Torres Blancas, although the examples are more associated with a petit-bourgeois lifestyle.

The City in Space. 1970 Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura. Source: RBTA

Swimming pool on the roof of the Walden 7 Building. Sant Just Desvern. (1975). Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura. Source: RBTA

Also in Madrid, the National Housing Institute focused on housing prototypes where the experimental nature of the designs addressed constructive, economic and sociological aspects. The housing complex Módulo L explored grouping modules in space according to complex compositional laws, aligned with the research of Taller de Arquitectura or other international examples from the moment such as Habitat 67 in Montreal, by Moshe Safdie, or buildings by Candilis, Josic and Woods.

While the previous examples focus on collective housing, solutions for workers’ housing were also tested out, in this case required by the scarcity of public resources that demanded maximizing and pooling shared services. The different Neighbourhood Absorption Units (Unidades Vecinals de Absorción, or UVA) are small neighbourhoods that were built quickly in Madrid using industrialized construction in response to the proliferation of shanty towns. The UVAs were outfitted with shops, a church, healthcare facilities, a bathhouse, school pavilions, a nursery, a building for administrative services and green spaces. In the official description from the National Housing Institute catalogue, the shared facilities are detailed as follows:

“Different pavilions, with highly varied modern architecture, were created in strategic places in each neighbourhood unit, where the residents of the UVAs can acquire everything they need for their daily lives. The pavilions house different shops to satisfy all their material needs. The healthcare pavilions built in all the new neighbourhoods have a surface area of 100 m2 and comprise offices for doctors, first aid supplies, and examination rooms. The administrative services pavilion, also measuring 100 m2, contains the mayor’s office, the post office, the police headquarters and offices for maintenance and upkeep. The bathhouses, separate for men and women, have hot water and different rooms allocated for washing, laundry, etc. There are fenced areas for rubbish collection. They are to be used by dwellings located within a maximum radius of 100 meters. They have running water and drains for cleanup, and they are surrounded by perimeter walls measuring at least 1.80 metres high”.1

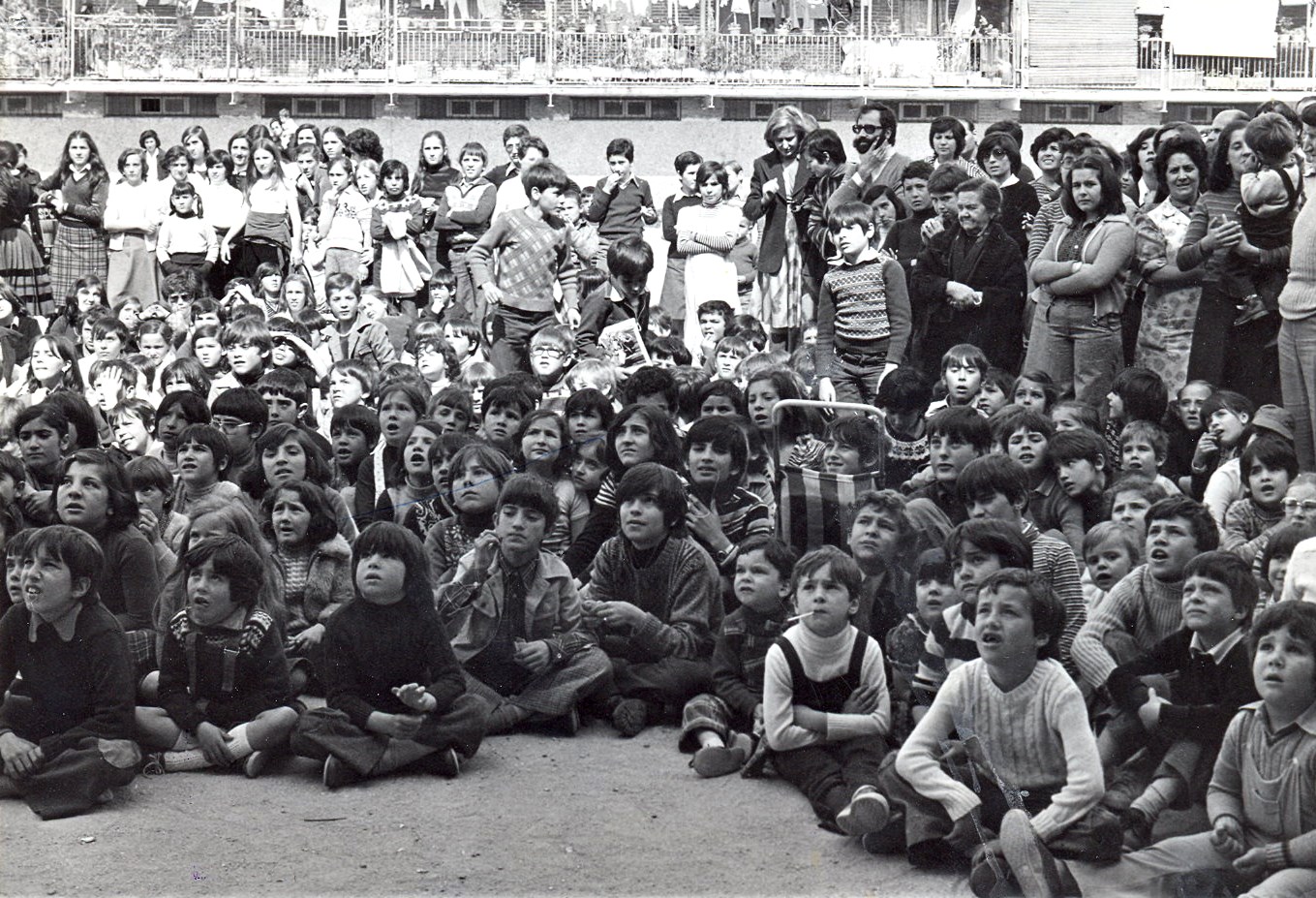

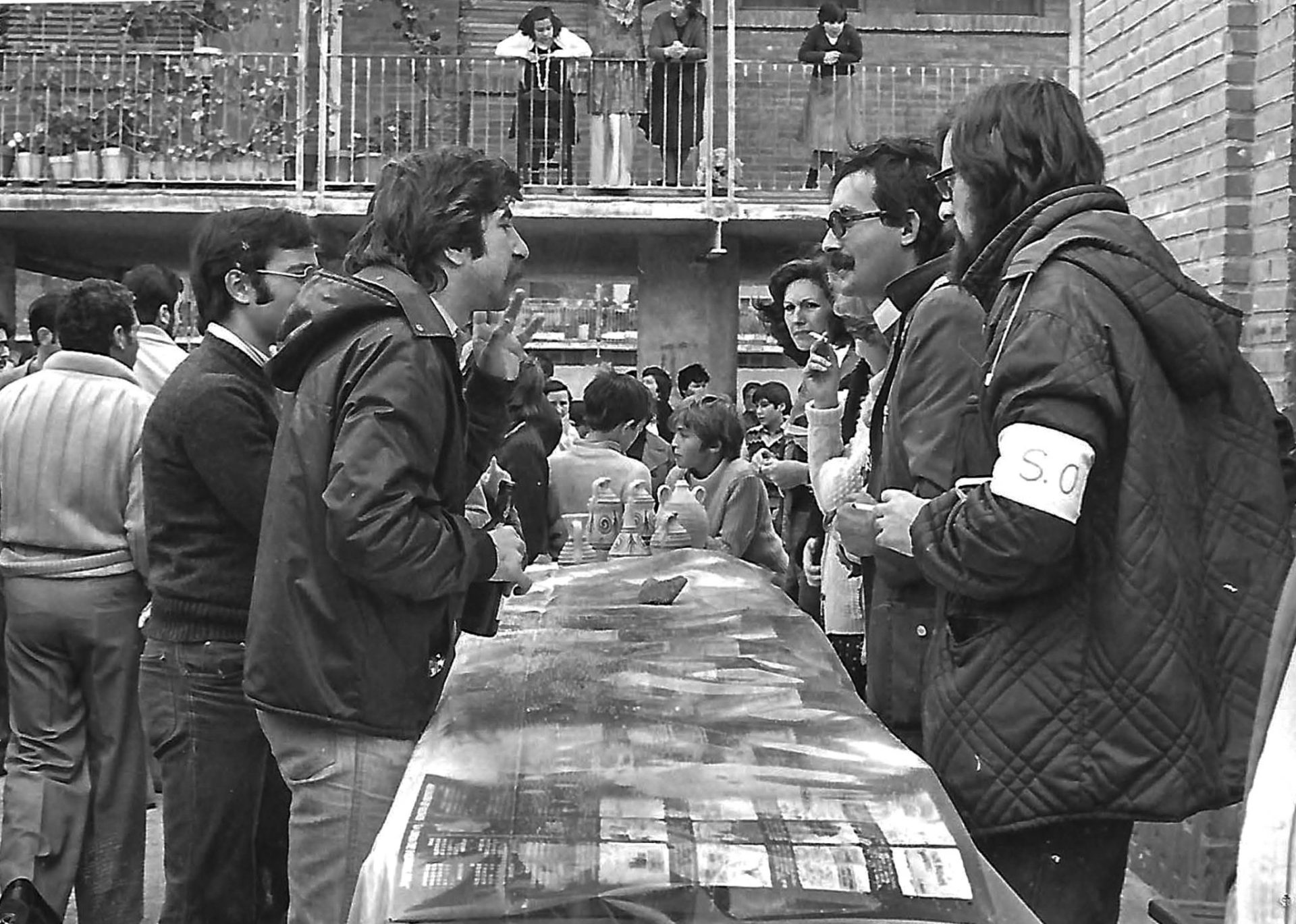

Spring festival at the UVA de Hortaleza. Source: Hortaleza Neighbourhood Newspaper

Majorettes during the spring festival at the UVA. 1977. Source: Memoria de Madrid (CC licence)

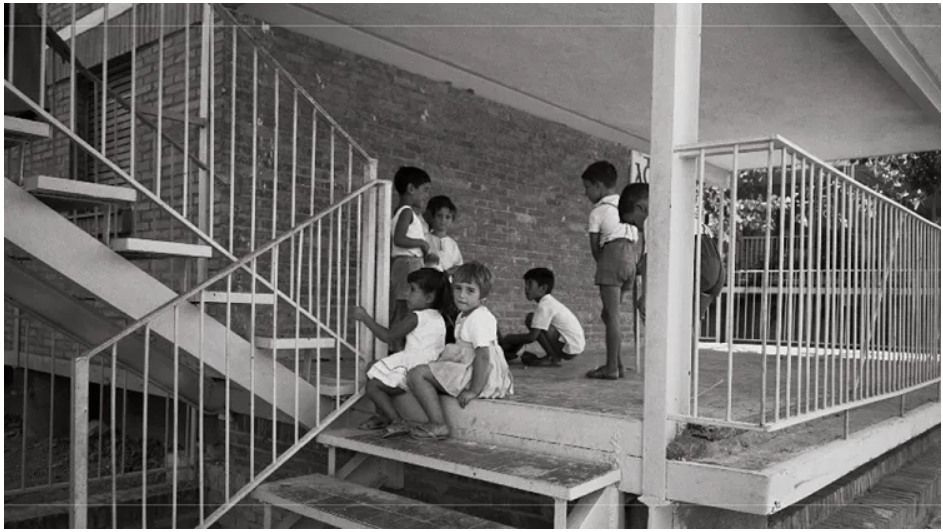

Children in the common spaces of the UVA de Hortaleza. Source: Hortaleza Neighbourhood Newspaper

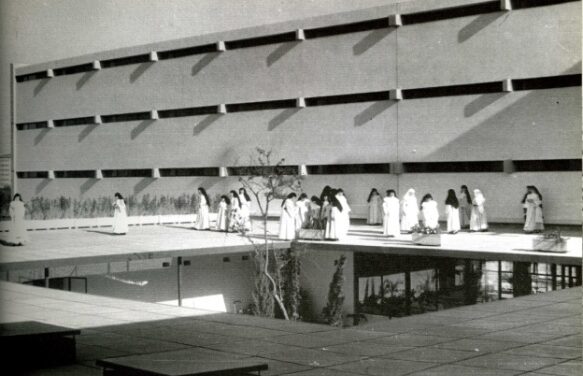

New Religious Communities

The contemplative life of religious communities is, by its very definition, a type of community life. Religious communities are organized based on a collection of norms that constitute what is called a “rule”; these norms often have consequences for the organization of living spaces and the relationships between the public and private spheres, within a community that is usually necessarily isolated.

Essential to understanding the importance and influence of these architectural models on how housing was conceived is a reflection by Le Corbusier who, when he was very young, visited the Florence Charterhouse in the Ema Valley. The organization of the cells, generating small private living units with a private garden, and the overall organization of the complex – the circulation areas, aggregations and relationships between public and private spaces and services – made a lasting impression on him. He later studied other models of convents belonging to the Carthusian order. In Precisions on the Present State of Architecture and City Planning (1930), Le Corbusier writes of the Charterhouse:

“I thought I had never seen such a happy interpretation of a dwelling. The back of each cell opens by a door and a wicket on a circular street. This street is covered by an arcade: the cloister. Through this way the monastery services operate – prayer, visits, food, funerals. This ‘modern city’ dates from the fifteenth century. Its radiant vision has always stayed with me.”

It wasn’t just Le Corbusier’s projects for religious communities, like the La Tourette convent, that were imbued with the architectural experience of Carthusian space; other typologies like his immeubles-villas, designed as an aggregation of individual units with their own garden and stacked in a block, are also related to the profound impression made on him by his visit to the Italian charterhouse.

Teologado de los Padres Dominicos in Madrid. Miguel Fisac. Source: AV

In Spain, the architecture of religious communities in the late 20th century produced a large number of buildings that are characterized by a radical modernity. The Franco regime placed religion at the centre of public life, especially in the period from 1943 to 1969, when the Falange party began losing power to ecclesiastical leaders. New congregations, like Opus Dei, were born, and the architecture associated with religious orders experienced a revival. After the Second Vatican Council (1963-1965), local churches took on a more central role; they were more progressive and with a marked social character, expressing new ideals through new architectural models. In general, the airs of modernization and innovation laid out by Vatican II meant that the new ecclesiastical and convent architectures also reflected the desire to rethink architectural and aesthetic models. Rationalist architecture offered the simplicity and evocative capabilities that they hoped to express. Miguel Fisac, Antonio Fernández Alba and Fray Coello de Portugal, among others, were able to lend the new religious architecture the sobriety and modernity heralded by the Council, although the most significant spatial implications affected the spaces for worship.

Miguel Fisac built an initial project for the Dominican order in Valladolid, the Colegio Apostólico, and its success led him to receive a commission to build the order’s convent, theology school, and church in Madrid. From this project, Fisac highlighted the difficulty of organizing the three types of users that form the three communities coexisting in the complex: teachers, ordained priests, and theology students.

Colegio Apostólico de los Padres Dominicos en Valladolid. Miguel Fisac. Source: Metalocus

Fray Coello de Portugal was himself a Dominican and unexpectedly began working on projects for the order, although he had assumed that his role as a member of the religious order would make it impossible for him to practice as an architect. Like Fisac’s projects, most of Fray Coello’s designs for convents also incorporated educational institutions. While Fisac’s designs often articulated the different parts using covered exterior paths that recalled historic cloisters, Coello’s projects were more forceful and based on a single volume. In the building for the Misioneras Dominicas del Rosario in Barañain, different blocks house different functions, but the convent building occupies a single block that is 115 meters long. More than 40 cells per floor are accessed through a single corridor that runs the entire length of the block.

Monasterio de Santa Inés in Zaragoza by Fray Coello de Portugal. Source: Zaragoza. Arquitectura. Siglo XXl

Source: Arquitectura Zaragoza Siglo XX

In the case of Fernández Alba, his knowledge and respect for traditional and vernacular architecture led him to respect the typological principles of monastic buildings. For the Convento del Rollo in Salamanca, the convent cloister is at the centre and organizes the complex, respecting the most canonical architectural configuration, with porticos and vaults. As is usually the case with monasteries, the pleasant interior space contrasts with the perimeter and exterior walls, which are solid and have few openings, emphasizing their protective role while offering isolation from the outside world.

With a similar configuration ─ although even more schematic ─ the Convento de las Madres Carmelitas Descalzas in Ourense, by José Javier Suances Pereiro, contrasts a staggered building for the cells with another dedicated to shared spaces and worship. The space between them is understood as a cloister, separated from the outside by two blank walls accompanied by minimal overhangs serving as a roof.

There are great examples of architecture for religious schools associated with the same principles as the new convent architecture. A large number of these buildings combined educational uses with accommodation for students and for the members of religious communities that served as teachers. Playing a similar role, although to a lesser extent, are halls of residence and sanatoriums where members of religious communities care for the sick, elderly or disabled.

Temporary Residences

Tourism or studying away from home are situations that require temporary housing in minimal accommodations – often just a bedroom with a desk and a bathroom, supported by shared services. Setting aside the hotel typology, we will focus on temporary residences; in that category, university halls of residence best exemplify the concept of community living, since they combine study with social and cultural activities. Historically, famous university halls of residence served as first-rate cultural hubs, and toward the end of the Franco regime, they became centres of activism and political engagement.

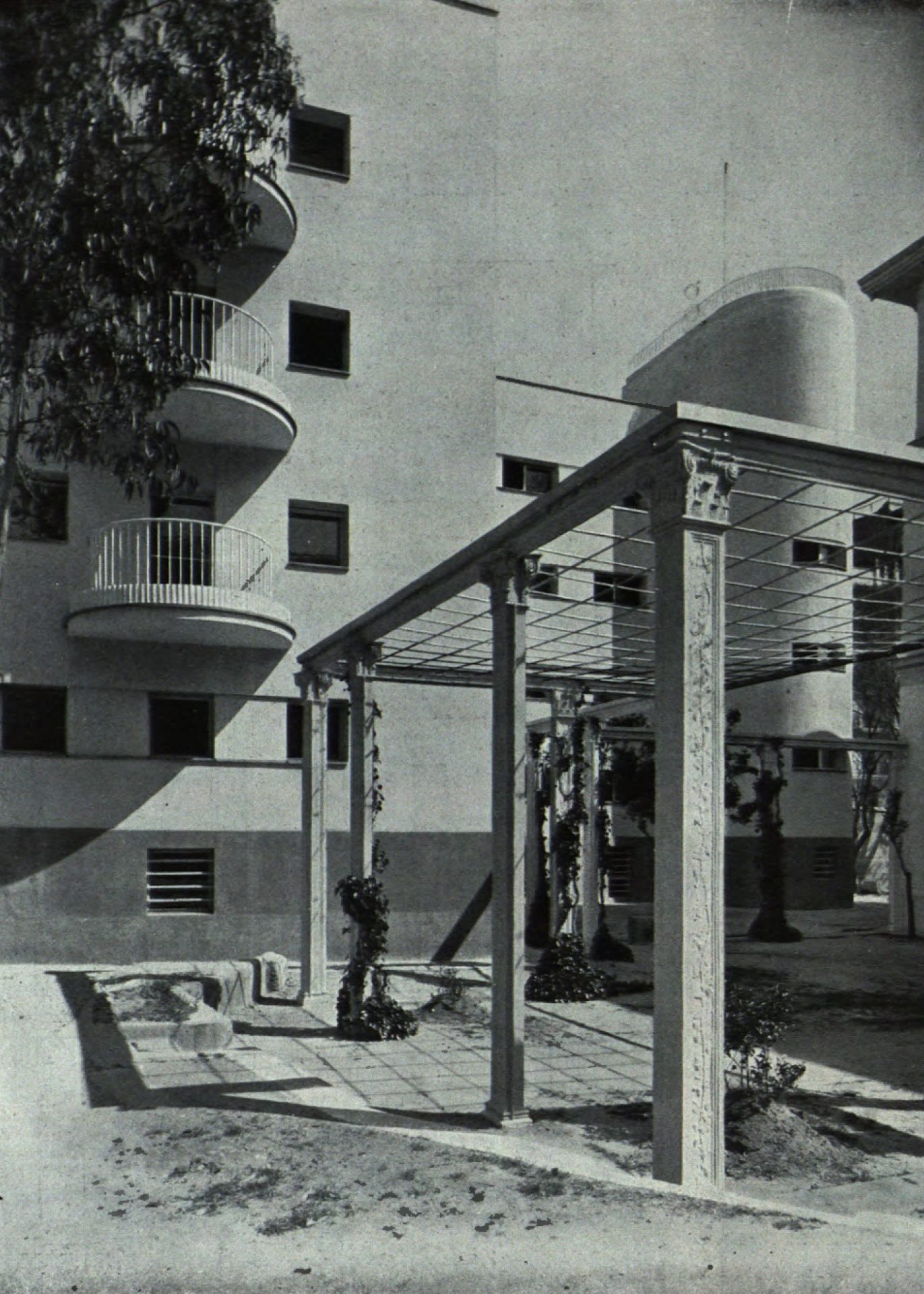

Courtyard of the Residencia de Señoritas. Madrid. 1932. Source: Fundación Giner de los Ríos

Although by the end of the 20th century there were many universities in Spain, at the beginning of the century only the historical universities existed, like the ones in Salamanca or Alcalá, for example, and the ones in large capital cities, many founded in the 19th century and with high expectations for growth. The Universidad Complutense was founded as an offshoot of the University of Alcalá in 1822-23, but its expansion was spearheaded at the end of the 1920s and in the later years of the Second Republic, just as the University City in Madrid was beginning to take shape. Its origins date back to a Royal Decree of 1927 by King Alphonse XIII, by which large plots of land in the Moncloa area were allocated to be developed according to a Master Plan by the architect Modesto López Otero. The promotion of university studies was key during those years, and new institutions such as the Board for the Expansion of Studies aimed to make it easier for students from different social classes to access university studies. Projects such as the Residencia de Señoritas in Madrid, from 1932, promoted the incorporation of young Spanish women into the ranks of university students.

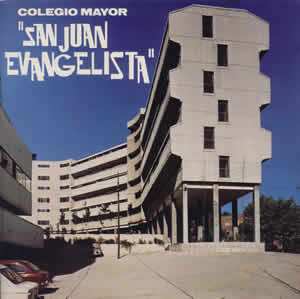

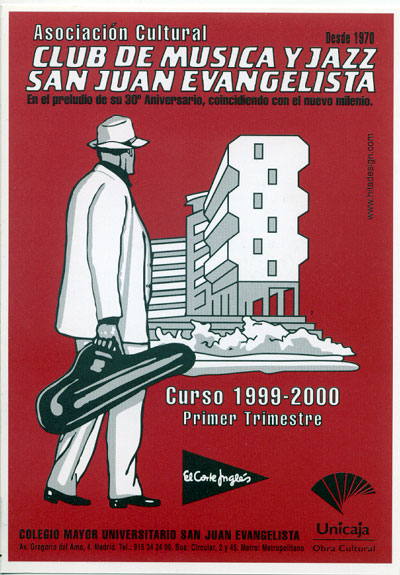

Posters from two editions of the Jazz Festival at the Colegio Mayor San Juan Evangelista in Madrid

Under the Franco regime, many of the halls of residence and residential colleges that were built in the University City were governed by religious institutions. Prestigious architects like Fray Coello de Portugal, José Luís Fernández del Amo, Alejandro de la Sota, and Ramón Vázquez Molezún built halls of residence for the Universidad Complutense, which became the main pole of attraction for students in the Spanish territory. As we stated earlier, many of these institutions became centres for political, intellectual and cultural agitation in the 1970s. This was the case of the San Juan Evangelista residential college, which, in addition to being a hub for political activism, became one of the most important centres for musical culture in the late Francoist era. The biggest names in music performed at its legendary Jazz Festival and it played a major role in the popularization of cante flamenco; Camarón de la Isla gave his final concert there in 1992. “El Johnny”, as the San Juan Evangelista was popularly called, closed its doors in 2004 and, today, has fallen into neglect.

Former interiors of the Siao-Sin residential college in Madrid.

Source: Informes de la Construcción, Volume 22, p. 219 (1970).

In typological terms, the residential colleges and halls of residence in Madrid were often characterized by their large size and by offering a wide variety of services in their facilities – for sports or cultural activities or spaces for socialization. In many cases, they were on plots surrounded by gardens. They are varied in terms of their architecture: the Santa María de Luján residential college in Madrid takes the form of a large, stepped amphitheatre, where the rooms open onto a garden. The Siao-Sin residential college is a much more compact building, with a brutalist concrete façade that is highly valued today. Unfortunately, the interiors – of great interest – have not been preserved, and it no longer serves its original purpose as a residential college.

Outside the core of the University City, we also find halls of residence and residential colleges in more urban contexts, both in Madrid and throughout Spain. Without a doubt, however, the concentration and high quality of the works in the Moncloa area of Madrid represent an unparalleled collection of examples of this typology in the Spanish territory.

Conclusion: Research on Collective Housing

In Spain, the financial crisis of 2008 laid bare the enormous dysfunctions in the residential market, with a nearly non-existent stock of public housing intended for rental. The “right to housing”, protected by the Constitution and which became a slogan and a talking point for political platforms, joined together politicians and legislators with architects in the search for imaginative solutions. At the same time, the limited capacity for public investment and the scarcity of available land made it necessary to invent, or borrow, solutions based on “new models of tenure”. In these solutions, community living and collective housing draw on longstanding research and historical typologies in which attention was focused on the relationship and the balance between private spaces and spaces for common uses in buildings and residential environments.

But those are not the only reasons behind the growing interest. There has also been a rise in tenant turnover in primary residences, together with changes in family structures; the aging of the population, which requires spaces that facilitate both autonomy and caregiving; job insecurity among young people that prolongs cohabitation models that were once limited only to periods of study; and environmental concerns that focus more on recycling and reconverting buildings than on demolition. All of this has led to experimentation with new solutions ─ such as occupying shipping containers with housing typologies ─ with conditions that offer new possibilities for community living. The demand ─ a necessity, in the wake of the pandemic ─ for access to transitional spaces between the private sphere of the home and public space and the city, together with the need for these spaces to provide respite – but also and above all, climate relief – has also generated new typologies.

Given the persistent housing crisis, it is also urgent to find decent solutions for the accommodation of people with a temporary need for housing due to economic reasons, migratory movements, etc.

In short, there has been a change in perspective regarding cooperative economic initiatives, grassroots associations, and the ideal of returning to models of cohabitation that industrial urban development had rejected. And, in the opposite sense, there are the exorbitant prices of options that present housing as a luxury, while introducing more and more shared services into the buildings to justify their sky-high prices, both for purchase and rental.

In recent years, relevant research has been carried out on historical models outside the European and Western context and their translations into contemporary models such as in the famous Gifu building by SANAA and Kazuyo Sejima (1994-1998), to highlight just one example among many. In the academic world, research groups like the one led by Xavier Monteys at the Technical University of Catalonia (UPC) have expanded perspectives on the meaning of collective housing in the 21st century. The academic research that has emerged from this group includes the work of Anna Puigjaner, who, under the title “Kitchenless City”, shines a light on models of cohabitation with shared services such as New York’s luxury hotels, where it was common to find stable communities of residents who benefitted from the establishments’ services. Without a doubt, in the coming years the study of historical models of community living will further stoke the revolution we are currently seeing in the typology of collective housing and the contributions that major public investment can make in terms of research and innovation.

Bibliography

- BRIONGOS, Anna Maria, CLOTET, Lluís, FAURA, Ramón, ROVIRA, Josep Maria, TUSQUETS, Oscar, La casa Fullà. Tot estava per fer i tot era possible, Editorial Tenov, Barcelona, 2023.

- ÁBALOS, Iñaki, Palacios comunales atemporales “genealogía y anatomía”, Puente Editores, Barcelona, 2020.

- FERNÁNDEZ-COBIÁN, “Fray Coello de Portugal y el debate sobre la pobreza en la arquitectura religiosa durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX”, in Arquitecturarevista, volumen 7, número 3, págs. 112-115, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos São Leopoldo, Brasil, 2011.

- PLA, Elisenda, RODENAS, Juan Fernando, Antonio Bonet: Poblat HIFRENSA, L’Hospitalet de l’Infant, COAC Demarcació de Tarragona, Barcelona, 2005.

- ÁLVAREZ ARCE, Raquel, La última comunidad walden (7). Taller de arquitectura y la vivienda colectiva (1971-1978) (tesis), Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2021.

- AA VV, 6 Unidades Vecinales de Absorción en Madrid, Ministerio de la Vivienda, Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda, Madrid, 1963.

Notes

1.- 6 Unidades Vecinales de Absorción en Madrid, Ministerio de la Vivienda, Ediciones del Instituto Nacional de la Vivienda, Madrid.