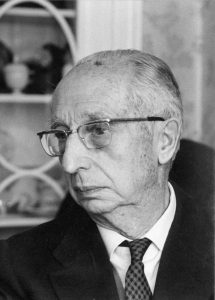

Francesc Mitjans Miró

Barcelona, 1909-2006

Francesc Mitjans earned his degree in architecture in 1941. He was an enduring architect with a long professional career. Before graduating, he was a member of the GATPAC and built some clearly rationalist works, such as the Casabó House. His first built work as an architect, the Oller House on carrer Amigó in Barcelona, was where he lived until he died. In it, he prematurely recovered the rationalist language during the autarkic years following the Spanish Civil War. His last projects were multi-family buildings in the Olympic Village in Barcelona from 1992, built in a language similar to that of the designs by MBM at the time. Consequently, his broad and lengthy professional career spanned the most relevant currents and incorporated the shifts in Catalan architecture over the second half of the 20th century, remaining faithful to, while constantly reinterpreting, the principles of modern architecture that influenced him so much in his youth.

Throughout his professional career, he reflected intensely on residential architecture. Initially, in the years after the Civil War, he built large homes in Barcelona’s “zona alta”, which were intended to be an alternative to the bourgeois housing of the Eixample, often in raised volumes designed for collective housing. As the “zona alta” densified, his projects also became more compact and denser, and the units became smaller in surface area. The housing problem also led him to reflect on the scale and construction of the city, a subject that interested him from the beginning of his career when he won first prize in the competition called “The Housing Problem” in 1947.

Although the construction of his first projects from the 1940s was traditional in nature, with load-bearing brick walls, Mitjans did not pick up the historicist language that he had been taught at architecture school, not even when the new regime rejected the languages most associated with rationalism. Mitjans talked about the great influence Mies van der Rohe’s architecture had on him – it is worth remembering that the Barcelona pavilion was built when he was already 20 years old and had shown a clear interest in becoming an architect. Perhaps for that reason, Mitjans once again embraced modernity soon enough, sharing the concerns of Grup R, although he was not a member.

The Oller House, from 1943, is one of the first examples in Barcelona of a break with the neoclassical language imposed by the regime, demonstrating that the new authorities were incapable of (or had no interest in) associating architectural language with an ideological expression. This early “return to modernity” astonished young architects, who saw the horizontal expanses of the building’s large terraces as an expression of architectural freedom. According to Mitjans, the aim was to bring the transition between city and dwelling onto the street façade – a transition that had been limited to the interiors of city blocks in the Eixample, and which Le Corbusier had praised during his visit to Barcelona when Mitjans was a student.

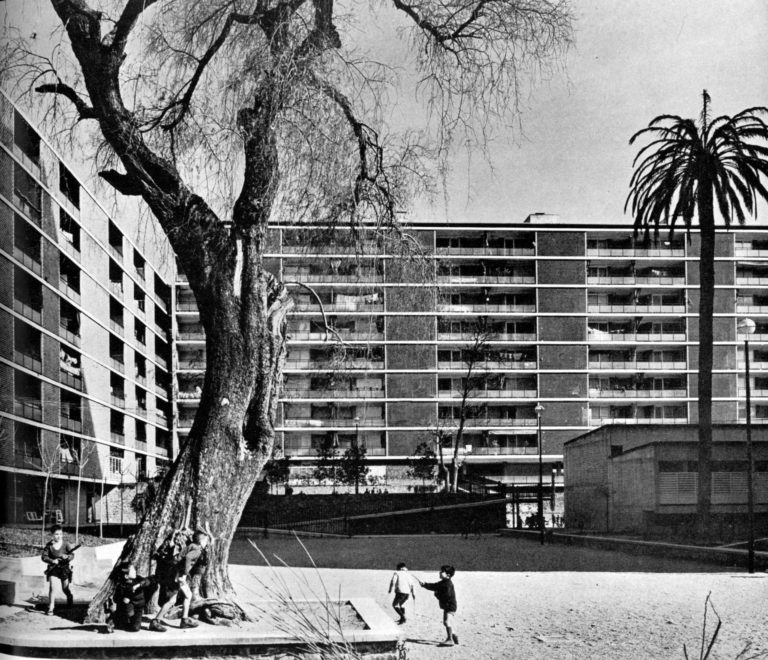

This reflection was continued in the Tort House and La Colmena House and in the Tokio building, where he added lightweight construction elements such as brise-soleils, awnings and sliding shutters to the façade. Mitjans never turned away from this reflection: the entire composition of the SEIDA building, a massive block over 100 meters long, can be understood as an immense brise-soleil built on the scale of the city, through habitable terraces and cantilevers. The building adopts all the principles of the modern architectural movement: the open plan layout, the ground floor on pilotis, flat roofs, and the use of reinforced concrete as a finishing material. Years later, in the Roma 2000 complex, Mitjans built one of the few examples of an open block typology, with a total of six high-rise housing blocks (without ventilation shafts), within the framework of Cerdá’s Eixample. He used reinforced concrete, not only in the structural elements but also for the façades and side walls.

The expressive use of reinforced concrete is also a hallmark of one of his most relevant and recognized works in Barcelona: the Futbol Club Barcelona stadium, the Camp Nou, which was considered the most modern and functional stadium in the world in its time.

Although Mitjans hardly left any legacy in the form of articles or interviews, his intellectual curiosity led him to travel more than other architects of his generation. On his travels he met Jacobsen in Copenhagen and visited buildings by Asplund, who, he asserted, was as much of an influence for him as the American Philip Johnson. In preparation for designing the Camp Nou, he also visited Paris, London, Zurich, Copenhagen, Basel, Berlin and Rio de Janeiro. The influences that came from his travels were reflected in projects such as the Banco Atlántico skyscraper, with clear connections to Gio Ponti’s Pirelli Tower in Milan.

In the final years of his career he was invited to teach at the school of architecture and received numerous awards, including the FAD medal in 2000.

Bibliography

- DPA 31 [Francesc Mitjans], Documentos de Proyectos Arquitectónicos, Departamento de Proyectos de Arquitectura de la Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2015.

- AAVV, Francesc Mitjans arquitecte, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya/Actar, Barcelona, 2012.

- CÁNOVAS, Andrés, ed., “Casa Oller: calle d’Amigó, 76, Barcelona, 1941-1944”, in AA VV, Vivienda colectiva en España: siglo XX (1929-1992), General de Ediciones de Arquitectura, Valencia, 2013, pp. 54-57.

- Mitjans, Francesc, COMPANYS, Antoni, Conversa amb Francesc Mitjans i Miró, Francesc Mitjans Arquitecte, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1996, p. 7.

- AA VV, Francesc Mitjans arquitecte, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1996.

- MONTEYS, Xavier, La Arquitectura de los años cincuenta en Barcelona, MOPU/ETSAV/COAC, Barcelona, 1987, p. 40.

- “Clasicismo, ̔espontaneismo̕ y estilo internacional: una incursión por la obra de Francesc Mitjans”, in Quaderns: d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme, 145, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1981, pp. 54-76.

- Mitjans, Francesc, “Inmueble en Barcelona”, en Cuadernos de arquitectura 13, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1950, p. 27.

Biography by Roger Subirà