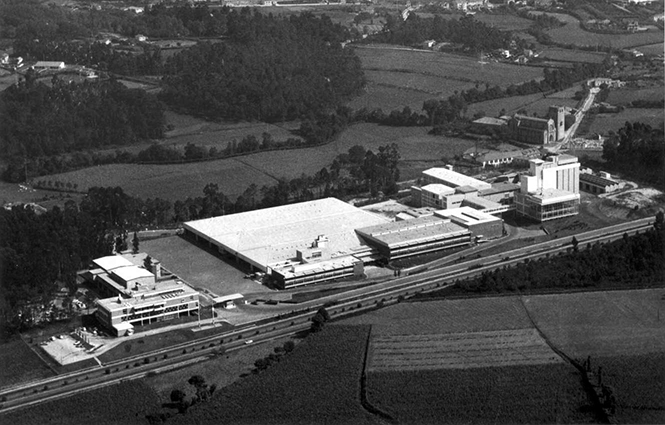

Publicamos dos nuevos reportajes fotográficos de Luis Argüelles: la Estación Marítima de Vigo y la Lonja de pescado de Ribeira (A Coruña).

Acceso al reportaje fotográfico de la Estación Marítima de Vigo

Acceso al reportaje fotográfico de la Lonja de contratación de pescado de Ribeira